Inheritance

1967 - United KingdomSet against the background of the development of the textile industry Inheritance was a novel written by Dr. Phyllis Bentley and although the TV series adopted the same title it was, in fact, based on this and two subsequent novels ('The Rise of Henry Morcar' and 'A Man of His Time') which revolved around the fortunes of the Oldroyds of Annotsfield, a Yorkshire mill-owning family, through five generations.

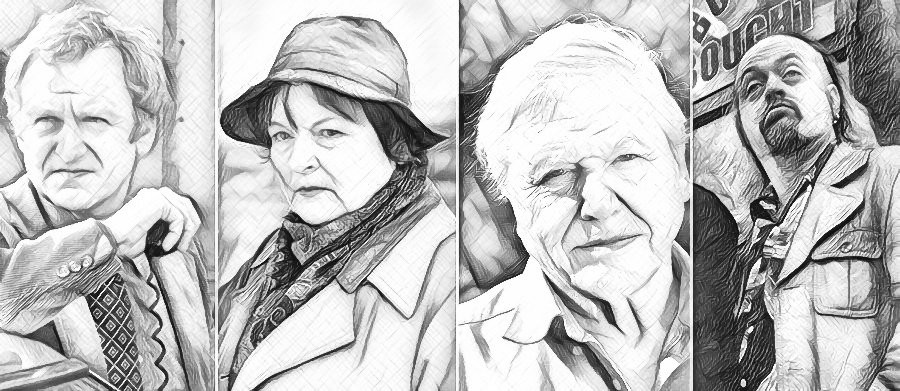

Inheritance became one of the most ambitious television serials ever attempted when it reached the screens in 1967. The story covered 153 trouble-torn years from the Luddite riots of 1812 to the death of Sir Winston Churchill in 1965. To get realism for the series, the studios recreated a woollen mill, complete with working machinery and furnaces, staged bomb-torn battle scenes and sent a train with 18th century coaches toppling over a railway embankment. John Thaw, James Bolam and Michael Goodliffe were the stars. Thaw played the menfolk of the Oldroyd family up to the age of 35. Then Goodliffe took over to play the older men in the same family. Bolam played the menfolk of the Bamforths, who violently oppose the Oldroyds. Between them, the three actors played 15 parts.

The first episode of Inheritance told the story of desperate opposition to the earliest forms of automation. "Cropping" the cloth had always been done by handshears. Then old Will Oldroyd, the mill owner hears of a blacksmith who claims to have invented a cropping machine which will cut down time and speed up production. More important to the workers, fewer croppers will be needed. The men protest, but Will is determined. He orders his first machines. The workers decide to fight - kill if need be - for their only livelihood. The war is on, with no holds barred.

A plot to wreck the machines as they are being delivered fails. The croppers are furious, and a second ambush is planned. But this time the target is human...Will Oldroyd himself. In the first episode Michael Goodliffe played Will Oldroyd and John Thaw played his son, young Will, who urges his father to be more cautious in his plans for modernisation. James Bolam played Joe Bamforth, one of Oldroyd's workers, a young man in the mill whose sympathy for the croppers leads him to join the Luddites. Joe is torn between loyalty to his employers and his sister (played by Thelma Whitley) who wants to keep him out of trouble, and loyalty to his workmates at the mill and the Luddite oath he swore.

The series was shot on location in the West Riding of Yorkshire, on the bitterly cold, windswept Pennine moors around the Calder Valley mills and down narrow streets of the millworkers' stone cottages. Sites weren't too difficult to find, for many of the dismal little two-up-and-two-down cottages were still there. Electric street lighting was replaced by gas lighting and tell-tale TV aerials were removed from roofs. In one episode, the production team had to recreate the 1915 World War I Battle of the Somme, in France. They built a second Somme battlefield - this time just outside Wigan, Lancashire. More than 60 actors took part in specially dug trenches for the battle scenes.

In a 1967 TV Times article, Phyllis Bentley told how she came to write the novel: "In December, 1930, I read D. F. E. Sykes' "History of Huddersfield." My mother had known D. F. E. Sykes in Huddersfield in his youth. She had often told me how this brilliant boy, at prize-givings in the Huddersfield Grammar School, was summoned over and over again to the platform to receive medals and prizes.

It was these memories which attracted me to his book, and my reading of it was a crucial incident. For in it I came across the story of the Luddites, the workmen, who in 1812, resented and resisted the coming of the new power-run cropping frames. At once I felt that this concerned me.

The years 1811 and 1812 had held the same atmosphere of wretched unemployment, manufacturers' struggle, mutual hostility, which the West Riding was experiencing in 1930.

Then, as now, there had been no attempt at rational discussion or adjustment. The results in 1812, of armed assault, murder, trial and hanging were frightening indeed. The results in 1931 were going to be frightful, too.

Now I knew that my novel must tell the story of the West Riding textile trade people from 1812 until the troubled year of 1931.

During the first three months of writing the book, I still remained uncertain of exactly what I was trying to say in it. But one day when I was being driven up to Wensleydale for a few days holiday, I commented to my driver on the usefulness of the device of a white line down the centre of roads, which was then a novelty to me.

"Who invented it?" I asked. The man didn't know. After a moment he expressed his regret for this. "It seems a shame to forget who it was when he's done so much for us," he said.

This was a key remark for me. After thinking about it for a few days the point of the book became clear to me. The name of the white-line inventor may be forgotten, but his invention lives on; one's actions, good or bad, always live on; they pass invariably down as an inheritance from one generation to another.

This decency and integrity, courage and compassion, were always worth while; they were not lost, but passed down the generations; we are always the heirs of the past and beggetters of the future ages. It will be seen that this thought is the meaning of the title 'Inheritance.' It is not material wealth which is meant, but a spiritual heritage."

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 23rd, 2018. Series description - modified version of an original article by Peter Lees, TV Times 1967. Phyllis Bentley in her own words, TV Times 1967. This article originally published 20 October 2008.