History of the BBC: Back After the War

On an October day in 1945 the Government announced that it wanted the BBC to start television again, on the pre-war technical system.

Within a few days those television engineers who had been demobilised were back inside Alexandra Palace. The next month, Maurice Gorham, who had been running the BBC's radio Light Entertainment Programme, was appointed Controller of Television.

Even before the programmes were re-started, Gorham was engaged in a battle with Broadcasting House. High level opinions there suggested that heads of programme departments responsible for sound radio should now become responsible for television departments. Gorham held that television was a full-time job, especially at directorial level, and would suffer if made to share direction with sound. He won his battle and was soon at Alexandra Palace to take a look round. The bombs had luckily missed the transmitters and the studios. Much equipment had been taken away, and every detail of the station, technical and structural, had to be overhauled before a start could be made.

The staff began to return, many of them from important Service jobs where they had earned more than the resumption of television was going to pay them. Most of them were so keen about television that they made the sacrifice. Denis Johnston was appointed Programme Director, and Gorham's deputy. A playwright and producer, from the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, Johnston had been a BBC producer in Belfast, and an outstanding radio war reporter. Douglas Birkinshaw was back as top engineer, after wartime duties running the great short-wave station at Daventry.

At the beginning of 1946 Gorham moved into Gerald Cock's old office in the Palace tower. During his three years there he never failed to show off the view his window gave of London spread out below. To him, a tall, broad-chested, hatless Irishman, there was always something exhilarating in the windy hilltop above Wood Green. His enthusiasm for television seemed to be fanned by the breeze. One knew that he was in it because he believed in it, and because he felt that it had all the spirit and enterprise which he had known in the early days of radio at Savoy Hill, and which he so sorely missed as the BBC grew up into an impersonal machine.

Gorham started his BBC career on the Radio Times and eventually became its editor. He ran the BBC's wartime programme to America, started by the Allied Expeditionary Forces Programme at the time of the Invasion, and followed up by launching the Light Programme. A rebel in many ways, he lasted longer than most rebels tended to in the BBC, and before he left had entered the highest of its inner circles.

At Alexandra Palace he found the engineers checking and patching up the old equipment. The austerity era had come, and new equipment was out of the question. The scenery, stocked throughout the war years in the damp Palace theatre, was all but intact, and Peter Bax's scenery department started repairing and painting until every piece, from a telephone box to a Viennese palace ballroom, was spick, span and fresh for action. The wardrobe, which had built up a valuable stock of clothes before the war, had suffered some war damage; but its stock was quickly renewed, dry-cleaned and ironed.

Soon the studios were buzzing again with cameramen, lighting experts, vision mixers, sound mixers, microphone boom men, producers, studio managers and presentation men. To get their hands in, they produced pictures in "closed circuit." George More O'Farrell started rehearsing The Dark Lady of the Sonnets, chosen to be part of the re-opening programme; and Michael Barry was rehearsing the first legacy of the war to television drama, a French Resistance play, The Silence of the Sea.

Announcers had to be found again. Although Jasmine Bligh was ready to come back, Elizabeth Cowell, after war work with the BBC as a producer, had married the laird of a Scottish estate, and was no longer available. Leslie Mitchell had become commentator of Movietone News, and was preoccupied with prospects in the film business. Over a hundred young men and women were tested before the cameras, and Winnifred Shotter, the actress known to lovers of the Aldywch Farces*, was chosen for one; and Macdonald Hobley for the other. Hobley was a young actor; freshly back from military service with SEAC, where he had taken part in Army broadcasting.

(*Between 1925 and 1933 the Aldwych was home to a series of farces by Ben Travers which became known as the Aldwych Farces).

Shortly after the opening, Jasmine Bligh left the BBC to marry a farmer in Ireland, and was replaced by Gillian Webb, who in turn left in 1947 to marry an American officer. She was replaced by Sylvia Peters, who had been a dancer in two Coliseum musical shows, and who won her television job by reciting the tale of the Three Bears impromptu before the cameras. Later Winnifred Shotter resigned, and was succeeded by Mary Malcolm, who had been one of the wartime team of women announcers on programmes to the Forces.

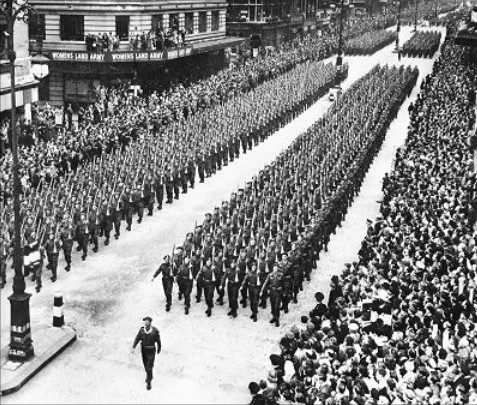

Gorham turned his eyes to a big outside event to give post-war television its send-off. This was Victory Parade, which had been fixed for June 8, 1946. The official re-opening of Alexandra Palace programmes was planned for the day before. For the Victory Parade all the outside mobile equipment had to be refitted and tested. The receiving mast for radio-link with outside points, which had stood at Highgate, had been blown down, and the local authority would not risk having it up again. So a new receiving aerial had to be fitted at the Palace. The special television cable, which had been laid round the West End before the war, had not, of course, been used for years, and had to be tested, and in places repaired.

On June 7, 1946, the BBC Television Service re-opened with another official ceremony, followed by Margot Fonteyn dancing, David Low drawing, and Leslie Mitchell introducing a variety show. That same Mickey Mouse cartoon, which had so suddenly closed down television on the eve of the war, was shown again. And viewers were taken over for a preview from the cameras already stationed on the Mall in readiness for the next day's great procession.

Televising the Victory Parade really put television back in the headlines. For two hours viewers watched every aspect of the procession and ceremony at the saluting base, seeing more than anyone pinioned to one spot by the crowds could possibly have seen. The home screens filled with close-up shots of the King and Queen, and the statesmen who had seen the country through the war, and those who were ready to tackle the ardours of peace. Once Princess Elizabeth dropped her programme card, and as she bent down to pick it up, viewers felt the intimate closeness to actuality with which television scored over every other medium.

The programmes soon began to assume their new shape. There was a more ambitious planning which did away with many of the short features familiar before the war. Plays were now presented in full; and variety was presented more ambitiously, and often for an hour at a time. Two highlights in that period were a programme viewers agreed was one of the best ever, and an "act" they were never allowed to see. Gracie Fields visited Alexandra Palace, taking her father and mother along with her, as well as her husband, Monty Banks. Henry Caldwell, a new young producer, who had been producing shows for the Forces in Europe and the Middle East, presented the show. When Gracie left the building after the show and as she walked to her car, crowds who had come out of their homes from Wood Green, Muswell Hill and Holloway mobbed her.

The event, which never reached the screens, was the televising of a hypnotist. Mary Adams, who had taken charge of the Talks-Feature Department, felt that hypnotism was a subject worth investigation and explanation. She interviewed Peter Casson, who was a hypnotist, but after a session or two with him, grew fearful of putting him on the air! The thought of viewers being sent off to sleep in their homes had all kinds of horrible possibilities to Adams and so a test was made for BBC staff and apparently half-a-dozen of them went off to sleep. The author didn't point out whether this was due to the effect of Casson's hypnotism or outright boredom with the subject matter, but the decision was nevertheless taken not to broadcast the experiment to viewers.

Television had come back but things were different. Alexandra Palace may have been buzzing with pioneers wishing to push the boundary of technology onto the next level, but the outside world was one of bleak austerity. The country was at the start of a fight for national recovery. Television was nothing less than a new system of broadcasting, and the nature of the times was against the revolution this implied. The whole future of radio might be involved, but it was no use expecting a government, bent on restoring the life blood of the national system, to give priorities to what was still, in practise, a luxury, enjoyed by a very small minority of the national population.

In his book "Sound and Fury," BBC Controller Maurice Gorham wrote: "I was running television in a country that could hardly afford it, for I do not think anybody would maintain that if we had not had television before the war we should have started it in 1946. Our equipment was hopelessly old fashion in design, the actual gear we used was mostly ten years old, and it was inadequately served. For instance, our outside broadcast unit still took to the road like a travelling circus with four enormous vans and thirty or forty men to operate it, when the Americans were using one small van and six to eight men. And the fleet that housed this cumbersome, antiquated equipment had no base; it literally had not got a roof over its head. Throughout the cruel winter of 1946-47 it could be seen standing on the parking space outside Alexandra Palace, whilst its devoted engineers did all the maintenance work on the complicated equipment in the open, and sometimes in the snow."

Down at Broadcasting House, Gorham pressed for decisions to be taken, at least, even if the material resources to implement them were as yet unavailable. He wanted plans made for the building of bigger studios; for new bases for film and outside broadcast units; for new cameras and accessory equipment in studios. He also began looking for a site for the Midland transmitter.

America, untouched by war delays, was already ahead of the UK in many forms of television from outside, but she had no studio programmes output as regular, as varied or as reliable as Britain. France had the very latest in studios and equipment, but hardly any programmes, and only a few dozen viewers. Other countries, starting television fresh, faced the same shortages of materials as the UK. It was because the BBC had a daily programme service, every item of which bore such promise, that frustration began to creep into Alexandra Palace's atmosphere as one post war year followed another without let-up in the material restrictions which were holding television down.

In February 1947, a Fuel Crisis closed down Television Service for a month. Denis Johnston left his job as Programme Director to get back to playwriting and theatre production. He was replaced by Cecil McGivern. Maurice Gorham was growing impatient at the slowness of getting decisions about the future development of television through the Television Advisory Committee, and he was always alive to the possibility of serious disagreements with Broadcasting House over the control of television, and the speed of its development. But neither he himself, nor anybody else in television, foresaw, in the autumn of 1947, that a change at the top was on the way.

In his book, Gorham tells the story which led to his resignation from the headship of the BBC Television Service. It began with a battle over obtaining sufficient staff for Television Newsreel. Through this it became apparent that changes were being prepared in the organisation of the high level control of the BBC. The position of television, and the powers of its chief were certainly implicated. Gorham did not see how he could stay in his job under the kind of organisation envisaged, and he said so. At this time he had lunch with the man who had succeeded him as head of the Light Programme, Norman Collins. They discussed the reorganisation, because both were disturbed by it.

The upshot of the reorganisation, and of Gorham's expressed reactions to it, was that Norman Collins was appointed to the leadership of television, and Gorham was asked to take over the Light Programme again. Maurice Gorham refused the offer and resigned from the BBC.

When Norman Collins took up his post at Alexandra Palace plans were well underway to embark on television's most ambitious project yet-coverage of the XIV Olympiad from Wembley was less than a year away. Colins would preside over BBC Television's first major television success that would see television ownership rise from a mere 15,000 to around 90,000 by 1949. But Collin's tenure as Controller of the BBC Television Service proved to be a stormy affair and would ultimately sow the seeds for the BBC's eventual loss of monopoly.

Related Articles: The First Television Era - Ally Pally's Secret War - The 1953 Coronation

This article was first published on Television Heaven's companion site Teletronic. A much fuller account of the BBC's early days as well as a comprehensive history of television can be found here.

Published on January 14th, 2020. Written by Laurence Marcus - Adapted in part from Here's Television by Kenneth Baily published 1950 for Television Heaven.