Genesis of the Daleks

Genesis of the Daleks is a signature story in the Doctor Who canon. In the days before DVDs and endless reruns, it was one of the very few serials that got a repeat showing by the BBC. Indeed, it was repeated more times than any other serial, beginning with a movie edit for the Christmas of 1975, its year of original broadcast, to its sudden appearance in 2000, when BBC 2 dropped the idea of running the full series of Pertwee serials and jumped ahead to a well-known favourite. While the video release didn't surface until 1991, the 1976 novelisation had the largest print run of any of the Target imprint's catalogue. A 1979 LP soundtrack release, and subsequent cassette edition, is a mainstay of fans' collections, and the first chance for many viewers to own genuine, performed Doctor Who.

Genesis has consistently been voted in the top three greatest-ever Doctor Who stories, 21st-century series included, often topping polls outright. At the time of broadcast, however, it was hugely divisive. Moral crusader Mary Whitehouse, by this time quite entrenched in her anti-Who crusade, famously described it as "teatime brutality for tots." While Whitehouse's obsessive desire to clean up television was little more than close-minded puritanism, it's hard to argue that she had a point. Genesis opens with a scene of death on the battlefields of a devastated planet, moving swiftly to the trenches and only getting more brutal from there. The story is uncompromising in its portrayal of the horrors of war and political murder. Nonetheless, the viewer response was largely positive, with feedback echoing the fan sentiment today. There's no denying the strength of the script and direction of the serial, even if some of the performances and effects leave a little to be desired.

The serial is classic Tom Baker era Doctor Who, which demonstrates just how quickly Baker came to embody the role. This is only his fourth serial, still in shouting distance of the Pertwee era. There's a clear progression from Baker's first serial, Robot, which simply has the new Doctor in the old Doctor's environment and playing with his toys, through the darker, more sombre future world of The Ark in Space, to this, where the new Doctor gets to make his own, indelible mark on the series' mythos. Baker is spectacular throughout, effortlessly shifting between some of the series' funniest moments - "Could you help me? I'm a spy!" - to uncompromising action and agonising moral dilemmas. Genesis of the Daleks takes the series' most famous, most popular alien monsters and makes them vulnerable. No matter how many times the Doctor had bested the Daleks before, now they became mutable, subject to greater narrative forces.

In a unique opening, the Doctor arrives on the planet Skaro sans TARDIS, diverted by the Time Lords mid-teleport. A Time Lord, looking as if he's just stepped out from The Seventh Seal, briefs him on his mission: to prevent the Daleks from coming into existence, or to somehow alter their destiny so that they become a lesser threat. This is not the sort of thing the Time Lords were expected to do. While Pertwee's Doctor had been sent on missions for them, this sort of rewriting of history was something we had hitherto expected to be entirely taboo. Fans later developed theories for how and why this change of policy happened. Some decided that this was the work of the CIA - the Celestial Intervention Agency, in this context - a group mentioned in passing in the following year's The Deadly Assassin. Much later, Russell T. Davies, the man who resurrected Doctor Who, would point to this being the first strike in the Time War between Gallifrey and Skaro. Other developments on this theme appear in the Big Finish audio series Gallifrey. Clearly, this out-of-character step made a significant impact upon fans of the series.

Indeed, it made a major impact on the series itself. Watching it, it's tempting to wonder if this was a dry run for a different direction for the programme, one that in the end, did not come to pass. Having freed the Doctor from his terrestrial exile, the writers and producers now set him on a series of linked adventures, the TARDIS nowhere to be seen. The substitution of the time ring, an altogether more compact method of travel, provides a dilemma similar to that perennially faced by William Hartnell's Doctor in the earliest days of the series. While Hartnell's stories often saw the TARDIS inaccessible, with the story revolving around finding a way back to it, the Time Ring becomes an easily lost or stolen lifeline for the new Doctor and his friends. It is not impossible to imagine the TARDIS being phased out of the programme in favour of a series of missions via time ring. In the event, this did not occur, with the Doctor being reunited with his trusty timeship in the following story, Revenge of the Cybermen.

This is World War II as if it had been fought for a thousand years...

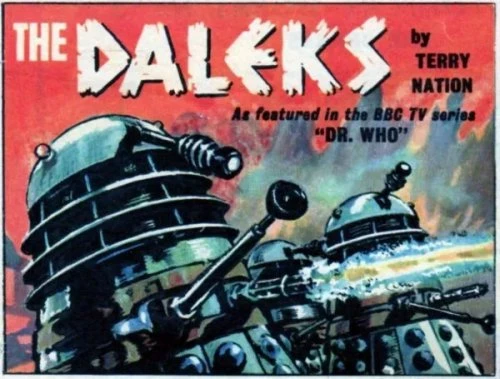

There are other ways in which the set-up of the series is being played with here. The very nature of the Daleks' genesis is entirely new to this story, an aspect that has become lost over the years as this has become enshrined in the series' mythology. Early accounts of the Daleks' origins are thrown out here. The fact that the Daleks' real-world creator, Terry Nation, wrote most of these accounts is by the by. From the rough accounts of the first Dalek serial of 1963 to the more in-depth but equally incompatible histories of the TV Century 21 comic strips and Nation's "We Are the Daleks" short story for The Radio Times, several possible origins had been suggested for the malign pepperpots. Nation's early conception of the Daleks had them as Nazi stand-ins, something most evident in their second appearance, 1964's The Dalek Invasion of Earth. They can, of course, be likened to any number of fascist groups, in their blind conformity, their hunger for power, and their hatred of the unlike. Here, though, the Daleks' progenitors, the Kaleds (a clunky but effective anagram) are explicitly pseudo-Nazis, from their uniforms and salutes to their desire for racial purity. Notably, their enemies, the Thals, previously shown as a noble people in the 1963 serial and its near remake, 1973's Planet of the Daleks, are little better in this portrayal. This is World War II as if it had been fought for a thousand years, with nothing left but two fortifications, shelling distance from one another, each side reduced to their most fanatical members.

The biggest change to the status quo, however, is Davros. The bile-spitting, crippled megalomaniac is the single biggest addition to the growing mythology of Doctor Who since the revelation of the Doctor as a Time Lord, six years previously. At a fundamental level, Davros is merely a mad scientist, a standard science fiction cliche. Even the concept of a humanoid creator of the Daleks is nothing new, having appeared in the largely David Whitaker authored Dalek strips of TV Century 21 many years earlier. However, Davros made a huge impact on the series. Much of this is down to the script, with Nation's original undoubtedly improved by the dialogue additions of script editor Robert Holmes. As with the Daleks, though, the true appeal of the creation is down to its realisation. Not only the spectacular design work, a combination of the prop of the Dalek-esque wheelchair and the prosthetics of Davros's ancient, shrivelled face, but also the performance. Michael Wisher had already done excellent work breathing life into the Daleks and other characters for the series, but Davros was his tour de force.

Davros is to the Kaleds as Hitler was to the Nazis. While there is no physical similarity, the impression remains the same. Wisher's delivery begins softly, yet insistent, his demands and propositions sounding quite reasonable, before building to a crescendo of raging madness. It's a hypnotic performance and one that easily brings to mind Hitler's ranting addresses to his adoring followers. In concept, too, the similarity is there. Davros, a poor, crippled husk of a man, barely able to function without his aides and life support, demands physical and racial purity, much as Hitler, a dark-haired individual of possibly mixed ancestry, was determined to see a fair-haired Aryan race dominate Europe. Davros takes his own megalomania considerably further, however. He has, as the Doctor puts it, "an insane desire to perpetuate himself," and his creations, supposedly the inevitable final mutation of his damaged people, are reflections of his own form. The peculiar design of the Daleks is put forward as nothing more than Davros basing his creations on his own damaged body, lacking legs and with a single artificial eye.

Davros's presence is so significant that it deforms the entirety of the Dalek story from this point onwards. The Doctor, at first, refuses the horrific choice to destroy the incubating Daleks, believing that this will make him no better than they. In the event, he agrees to try, but succeeds in only, in his words, delaying them. Quite how much credence we can put on his claim that the Daleks were set back a thousand years is uncertain, but from now on, Dalek history has been affected. Before Genesis of the Daleks, there was no mention or hint of Davros's existence. From now until the original series' final Dalek story, Remembrance of the Daleks in 1988, they are inseparable. The material cause for this is uncertain. Perhaps the Doctor's near murder of Davros, holding him hostage as his hand hovers over his (absurdly exposed) life support control switch, inspired the scientist to install more safeguards into his systems, keeping him in suspended animation when he would otherwise have been killed. We can't be certain. In any case, the difference is that Davros does survive.

Admittedly, this can be seen as something of a mistake. Wisher's Davros was set to be one of the series' greatest one-off villains, and his death at the hands of his own creations was a fitting end for his character. Four years later, however, the character was revived, by both Nation and the production team, and by the Daleks themselves. Thus began an obsession with the Daleks' creator, in which the Daleks were no longer masters of their own fate. Everything was about Davros for them now. Like the Daleks before him, who had begun as desperate survivors but were reinvented as conquerors of worlds, Davros was repurposed to become the Doctor's new arch-enemy.

David Gooderson's portrayal of the character in Destiny of the Daleks is not well-remembered, but Terry Molloy, a talented voice actor, breathed new life into the despot in Davros's subsequent three appearances. It was only with the revival of Doctor Who that the Daleks had a chance to slide out from their creator's shadow and act with their own agency again. Even then, die-hard fans and casual viewers alike wondered, "When's Davros going to turn up?" In 2008, he finally did, played with aplomb by Julian Bleach. While we've been introduced to Dalek Emperors, a Cult of Skaro, even a Dalek Prime Minister, it's inevitable that someday, Davros will show his ugly face again.

Before Genesis, it had always been the Doctor and the Daleks. After Genesis, it was the Doctor, the Daleks and Davros. An antagonistic triangle of mutual hatred, fear and respect.

Review by Daniel Tessier