Doctor Who - New Beginnings

Article by Daniel Tessier

Doctor Who is unique amongst television series in its ability to relaunch and revamp itself periodically. When it was first contrived by the BBC's Head of Drama Sydney Newman and others on his staff, the concept of regeneration was nowhere to be seen. The idea of transforming the lead character in order to recast was one born of necessity as much as creativity. Successive creative teams have approached the casting of the Doctor and the challenge of introducing the character in very different ways over the years, as the style of the series and television itself have changed.

In the beginning, producer Verity Lambert, director Waris Hussein and story editor (today script editor) David Whitaker, armed with a loose outline, had commissioned several scripts before settling on one by Anthony Coburn. After many actors were considered, William Hartnell was cast as the title character. Best known for gruff army types and hard men in series and films such as The Army Game, Carry on Sergeant and Brighton Rock, it was his more grandfatherly role in This Sporting Life that led Lambert to suggest him for the part. The first episode was initially filmed as a pilot, which was deemed unfit for broadcast and remounted with a number of tweaks, and this is where the story really begins.

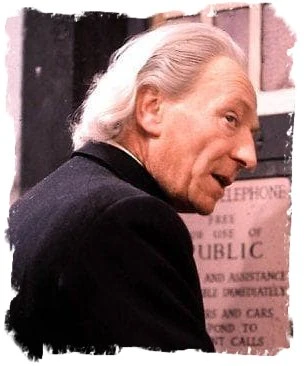

William Hartnell: An Unearthly Child (November 1963)

An Unearthly Child is the evocative title of the first episode of Doctor Who, and also the title generally given to the entire four-part serial that began the series. (The practice of onscreen umbrella titles for serials didn't come into effect until 1966, and behind-the-scenes usage was inconsistent. The BBC favours An Unearthly Child, but 100,000 BC and The Tribe of Gum are popular alternatives.) As the title suggests, the first episode focuses a great deal on Susan, the Doctor's granddaughter. Indeed, this early in the series' history, the Doctor is only one part of an ensemble cast, with Susan and her teachers Ian and Barbara as important as the title character. Indeed, to an uninitiated viewer at the time, Ian would appear to be the hero of the piece, as the young male lead, played by William Russell, best known then for swashbuckling heroic series such as The Adventures of Sir Lancelot.

Mystery is at the heart of the first episode. After the hypnotically strange opening titles, with Delia Derbyshire's ground-breaking electronic music and the warping video effects, the scene resolves into a very mundane sight, at least for viewers in 1963. Watching now, it's hard to see a police box as anything other than a TARDIS; indeed, the BBC now owns the copyright to that specific design. To the contemporary viewer, the sight of a policeman walking past a police box on a foggy night was not particularly strange. The electrical humming that accompanied it, and the juxtaposition with the uncanny opening titles, set it apart as something peculiar.

From then, the episode moves rapidly into the confines of Coal Hill School, where we meet Ian Chesterton (Russell) and Barbara Wright (Jacqueline Hill), science and history teachers respectively. They're clearly close colleagues, and talk openly about the bizarre gaps in knowledge of their newest pupil, Susan Foreman (Carole Ann Ford). Her scientific knowledge is far beyond what a schoolchild should know, while her historical knowledge is exceptional, yet her understanding of straightforward everyday matters is sorely lacking. (One element, amusing seen today, is that she forgets that Britain isn't using decimal currency yet – eight years before it was introduced in reality.)

There's little mention of her grandfather to begin with. “He's a Doctor, isn't he?” remarks Ian, but that's all there is to it. He and Barbara are more intrigued by the fact that Susan's address apparently applies to a junkyard. After their offer to give her a lift home is rebuked, they decide to engage in a little light stalking and follow her home – something that would absolutely not play well on a 21st century series. It's when they enter the junkyard that they discover the TARDIS, and are then confronted by Susan's grandfather. Hartnell's Doctor is a far cry from the heroic figure we'll get to know later. He's sinister, obstructive, mocking the two teachers' understanding of events. He isn't even really called the Doctor (“Eh? Doctor who?”) It's simply taken from Ian's assumption and he never bothers correcting him. There are elements of the character we'll know later: he's distractable and eccentric, and of course, already decked out like a gentleman from the early twentieth century. This Victorian/Edwardian look is visual shorthand for “eccentric,” but it will become so associated with the Doctor that the character will gravitate back towards the style time and again.

Upon hearing Susan's voice coming from the police box, Ian and Barbara force their way in, only to find themselves in the interior of the TARDIS. In contrast to some later versions, but in keeping with the modern series, the control room is huge, with all manner of knick-knacks and technology surrounding the unfathomable central console. The two teachers are understandably baffled: Ian tries his best to rationalise it, while Barbara, rather patronisingly, tells Susan that the Ship see describes is all a game. The Doctor dismisses their lack of understanding, coming up with a throwaway explanation likening it to how a television allows a huge building to fit into a small room, before waxing lyrical about his and Susan's origins. “I tolerate this century but I don't enjoy it,” he says, before claiming to be cut off from his own planet. It's not quite clear whether they're humans from the future, or alien beings, but he and Susan clearly do not belong in the twentieth century. We're still six years away from the coining of the term “Time Lord.”

It's the Doctor who insists that he and Susan can't stay, and that the two teachers can't be allowed to leave and put them in danger, in spite of having just told them he's a time-travelling exile. Susan refuses to leave, which the Doctor is having none of. When Ian tries to leave, the Doctor locks the doors and electrifies the console, before taking off, abducting the two teachers. The weird visuals of the title sequence overlay the events, as the now familiar, but then unsettling sounds of the TARDIS engines accompany a terrifying journey. Ian and Barbara are rendered unconscious, and even the Doctor seems unsettled by the trip.

In Doctor Who's first, astonishing cliffhanger, the police box appears incongruously on a devastated plain, as the shadow of an unknown figure looms over it. It's an incredible image, bringing to a close a seminal piece of television – all that in just the first twenty-five minute episode!

However, An Unearthly Child is just the first episode of the serial. Fans often overlook the remaining three – The Cave of Skulls, The Forest of Fear and The Firemaker – but they are just as essential to the story as that remarkable first episode. There's a palpable sense of danger throughout, as the Doctor, nipping off for a smoke on his pipe, is abducted by a hungry Neanderthal in a clear reversal of his kidnap of the two teachers. The four regulars are all excellent throughout, as the sheer terror of being thrown into this situation, completely out of their control, their lives continuously on the line. There's a poetry to the new status quo, with the two twentieth century humans really no different than the two time-travellers. They're all millennia ahead of their captors, and all just as helpless. Still, it can't be denied that after the confident strangeness of that opening episode, three episodes of cave men politics is hardly the most gripping follow-up. While the cast all do what they can, watching Palaeolithic humans slowly argue with each other lacks finesse, and the action rapidly becomes a repetitive series of captures and escapes.

Nonetheless, we learn a great deal about our core characters in that time. Barbara is the most compassionate, risking their escape to help their pursuers after one of them is injured, while Ian is pragmatic but caring, and clearly swayed by Barbara. Susan is creative but terrified by the untamed world around them. The Doctor is surprisingly defeatist, but clever, coming up with solutions when he's cornered and learning how the cave men's minds work. “I'm sorry, it's all my fault,” he says, a contrite confession from someone who was so arrogantly assured not long before. He's also the most dangerously pragmatic, ready to smash the injured Neanderthal's skull in with a rock in order to make good their escape. It's clear the Doctor has a lot to learn from his unwilling companions, and outwitting a bunch of Stone Age tribesman will hardly go down as his greatest victory.

But the seeds have been sown. The travellers escape back to the TARDIS, and enter flight once more, with no way of knowing where or when they are going. Every episode ends on a cliffhanger, the final one of the serial no different, leading directly into The Daleks , a story which will cement Doctor Who's concept and success.

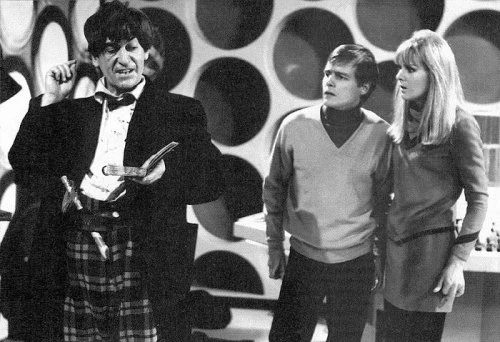

Patrick Troughton: The Power of the Daleks (November 1966)

Fast forward three years. Doctor Who has become a phenomenon. Most of the original cast have moved on, but William Hartnell remains, having seen out successive teams of companions and grown into the role of the Doctor, which has, thanks to him and the writers, developed into a more humorous, heroic character. Hartnell is now very much the hero of his own series, the one actor completely identified with Doctor Who. Unfortunately, he has to go. As his health has deteriorated, Hartnell has become harder to work with and unable to keep up with the brutal production schedule, and so he is to be replaced. Creatively, this is something of a challenge.

The creative team, led by producer Innes Lloyd, came up with an ingenious solution. The Doctor had been more-or-less established as an alien by now, or at least something beyond human, and there had never been anything in the series that said he couldn't just turn into someone else. The job of re-casting the Doctor must have been difficult, and to their credit, the team decided not to try to simply recreate the role as was and instead cast the noted character actor Patrick Troughton, who had played title roles in everything from the 1956-60 Robin Hood to 1960's Paul of Tarsus. So, at the close of The Tenth Planet and the Doctor's first encounter with the Cybermen, the Doctor's old body, “wearing a bit thin,” collapses and he transforms into a new Doctor. Even his clothes change. We're some years from the coining of the term “regeneration,” with the process described as a renewal, but this is the invention of a concept which will ensure Doctor Who's longevity.

This takes place partway into Doctor Who's fourth season, with The Power of the Daleks introducing Patrick Troughton's Doctor fully. The writers, David Whitaker and Dennis Spooner, take the brave but ultimately correct direction by making the new Doctor a figure of mystery and uncertainty, for the first time since the beginnings of the series. After all, the audience, like the swinging sixties companions Ben and Polly, are utterly thrown by this sudden transformation. “'What 'im? The Doctor?!” says Ben (Michael Craze). “This old body of mine is wearing a bit thin,” repeats Polly (Anneke Wills). “So he goes and gets himself a new one?” Ben is utterly untrusting of the Doctor, and it's not hard to see why. He's immediately sinister, laughing to himself, giving opaque answers to questions and referring to the Doctor in the third person. Polly is more open-minded, but she's still wrong-footed at first. “It's a very different Doctor,” she says, although the change between Hartnell and Troughton's portrayals isn't as pronounced as some would say. Hartnell's Doctor became more heroic and humorous over his three-and-a-bit seasons, and while Troughton's starts off with silly hats and a tootling recorder, he still has the edge and untrustworthiness that characterised early Hartnell. The Second Doctor is a continuation of the direction the First Doctor had been moving.

From the Doctor's perspective, the transformation seems horrifying. He's assailed by disoriented, swirling vision and an excruciating noise. “Concentrate on one thing,” he says to himself, trying to make it through the disorientation, but he still sees his former reflection in the mirror. He mutters to himself, mentioning his adventure with Marco Polo (Hartnell's fourth serial) of all things. Ben demands he try on his ring – an almost magical item that the First Doctor used in some of his stories – and it falls straight off his finger. The script seems to equally suggest that this isn’t the Doctor and that he's some interloper.

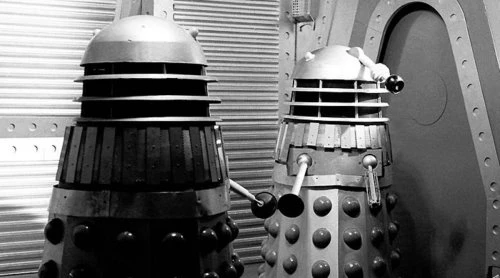

Even the other two regulars are fairly new, and not entirely known elements. Cleverly, the writers make the Daleks, by now as recognisable as the Doctor, the familiar element in the programme. Even this isn't straightforward, though. The Daleks are introduced gradually, their initial appearance as three dormant shells in a cobwebbed, dilapidated spacecraft, then revived with electricity, only to declare their subservience to the human characters. “I am your ser-vant!” one announces, a cry that would much later be refigured for Victory of the Daleks in Matt Smith's debut season, an altogether unnatural thing for a Dalek to say. The suspense generated from the human colonists of the planet Vulcan not knowing what these creatures are is palpable. The audience knows the aliens will betray them. When the Daleks revert to their evil ways, it's strangely reassuring; their recognition of Troughton's character as the Doctor cements him as the same character we know from before.

Sadly, The Power of the Daleks is one of many serials that was wiped in the BBC's archive purge, and none of its six episodes is known to survive. Troughton's tenure was particularly ravaged by the purges, but his debut story is perhaps the greatest loss of them all. However, all episodes survive as soundtracks, and Power has been released on DVD with an animated reconstruction. While only those who saw it on broadcast can know exactly what it was like, we can still enjoy a version of this seminal adventure.

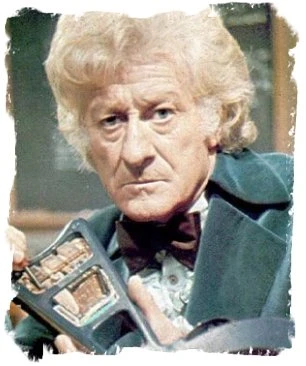

Jon Pertwee: Spearhead from Space (January 1970)

The move to colour heralded the biggest format change in Doctor Who's long history. The sixth season had run into considerable problems, many of them budgetary, and came close to being the series' last. For season seven, a new approach to the series was devised, changing what had been a programme about adventures in time and space to one about Earth-based military operations. To begin with, Derrick Sherwin acted as producer, as he had on The War Games , the final serial of season six. Working with him on the first serial of season seven was Terrance Dicks as script editor, co-writer of said serial, who would shape much of the series to come.

Many of the elements that came into play in Spearhead from Space had been tested out earlier in Troughton's run. Contemporary and near-future stories occurred with far more frequency than in Hartnell's era. The fifth season serial The Web of Fear introduced Nicholas Courtney as Colonol Lethbridge-Stewart, who would appear after a promotion to Brigadier in the following year's The Invasion , heading up UNIT, a new taskforce dedicated to defending the Earth (well, mainly southern England) from extra-normal threats. On the more alien end of the scale, The War Games introduced the Time Lords as the Doctor's people, who punished him for the theft of his TARDIS and exiled him to Earth in the twentieth century.

After an unusually long six-month gap between seasons, Jon Pertwee was cast as the new Doctor. Better known for his voice than his face due his long radio career (including the hugely popular The Navy Lark), Pertwee had nonetheless made a number of screen appearances. Best known for comedy, he was perhaps the first big name star to be cast as the Doctor. Cannily, the first episode of Spearhead keeps his face obscured for much of its run, as he collapses out of the TARDIS, still in his predecessor's costume, and lands flat on his face. He is carted into hospital, where it is some time before we get a good look at the newcomer. However, the effectiveness of this was rather undone by the impressive new colour title sequence, which included Pertwee's looming face as part of the visuals. Nonetheless, scriptwriter Robert Holmes maintains as much mystery as possible about this new Doctor. The episode opens with the Earth in space, before moving in to a UNIT monitoring station, and then focusing on local characters as meteorites fall to Earth. We then meet Professor Elizabeth Shaw (Caroline John), a highly skilled scientist, drafted by the Brigadier, who handily introduces UNIT's remit and with it the new format for the series. “We deal with the odd... the unexplained. Anything on Earth... or beyond.”

Only then do we follow him to hospital to see the man who was recovered from the foot of a Police Box, who, when finally revealed, dumbfounds the Brigadier by not being Patrick Troughton at all. He is revealed to have two hearts and alien blood, pushing home how the Doctor is not a human being, as if being based on Earth requires his alienness to be stepped up. The Doctor is incoherent for much of his first episode, something that will become habitual for a newly manifested Doctor. To begin with he's obsessed with finding his shoes, since that's where his TARDIS key is hidden, and laments over the new face in the mirror, although he soon admits it's “quite distinguished.” After a comedy escape attempt in a wheelchair, the Doctor is injured and spends the better part of another episode recuperating in hospital.

It's a drawn out introduction for Pertwee's Doctor, and it works, keeping up the tension of his introduction. We've had a change of Doctor before, and so the tension isn't over whether this is really the Doctor, but what he will be like. Equally, it gives the Brigadier and UNIT breathing room and the chance to establish themselves as a significant part of the series' new format, as they investigate the oddly plastic meteorites. Pertwee is able to settle into the character at his leisure, picking out a fancy new costume (stolen from the hospital, and not for the last time), before he pinches a vintage car which illustrates his dashing, adventurous new persona. Once he's himself, he is magnetic, charming Liz Shaw easily. However, in this first serial, there's still a lot of Troughton to the character; his second escape attempt in the TARDIS and his contrite, naughty-schoolboy telling off are clearly written with the previous Doctor in mind.

The serial has a distinctly modern feel compared to the monochrome programme before, and not only because of the colour. It has contemporary music laid over grimy footage of industrial operations, with a factory manufacturing dolls providing an unsettling base for the alien operations. A striking new alien enemy is introduced: the Autons, plastic androids that are immune to bullets, are armed with their own guns and, unusually for Doctor Who monsters, can run. They can hide as shop window mannequins or as custom-made human duplicates, both of which make them extremely unsettling. The only thing overlooked is to actually have Auton dolls, which wouldn't be tried out until the following season, and still wouldn't be as creepy as the real dolls in the factory. When the Doctor finally confronts the Nestene – the Auton's controlling intelligence – it's rather disappointing, little more than a plastic bag in a tank. It does give Pertwee a chance to show off his gurning skills as he wrestles with a tentacle, but at the end of the day, he defeats the aliens with a hastily built gizmo and plenty of military back-up.

The serial ends with the Doctor accepting a position as UNIT's scientific advisor – rather doing Shaw out of a job – as long as he can work on his TARDIS and have a fancy new car like the one he “borrowed.” The rest of the Pertwee era would be produced by Barry Letts, with Dicks continuing as script editor. They would shape the era, slowly moving it away from Earth, featuring more Time Lord characters and gradually bringing the series back towards its original format.

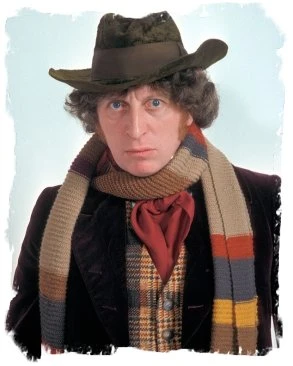

Tom Baker: Robot (Dec 1974 to Jan 75)

Tom Baker, now inarguably the most popular of the original series Doctors, had a harder job than Pertwee. He had come in only three years after the last recast of the lead, and then stayed on for five seasons. Tom Baker had to take over five years after the last recast, during which time Doctor Who had become more popular than ever. Baker was also a much lesser known figure than Pertwee, having only fairly recently become a successful actor with big screen roles in Nicholas and Alexandra and The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, and was by 1974 out of work as an actor altogether. He was also, at forty, notably younger than his predecessors in the role, even though the trend for younger leads as the series progressed mean that this is now the average age for a Doctor.

Behind the scenes it was almost an inversion of Pertwee's debut. Barry Letts stayed on as producer for one more story, with Robert Holmes now script editor and Terrance Dicks scriptwriting. Whereas Spearhead from Space had to establish UNIT as the new status quo, the Fourth Doctor's debut had to write them out. Having the first serial for the new Doctor feature familiar elements was, like having the Daleks in Troughton's first story, a good way of maintaining continuity for new viewers, reassuring them that this was the same series. In effect, though, it meant Baker had to act alongside his beloved predecessor's cast, very much in his shadow.

It's remarkable, then, that Baker owns the part immediately. He's very different to Pertwee: considerably younger, far more erratic in his performance, stranger looking and less obviously a leading man. However, he dominated the screen from the first moment we see him. The first episode of Robot recaps the regeneration – now named so – and has the Doctor babble about Sontarans and the Brontosaurus among various bits of nonsense, referring back to the previous season's stories. After that bit of housekeeping is out of the way, the new Doctor takes over, bringing a new kind of anarchy into the programme. His chemistry with Elisabeth Sladen as Sarah Jane is palpably greater than Pertwee's was, and he brings the Brigadier back to his earlier, exasperated character, rather than the very chummy relationship the Third Doctor shared with him. The episode also introduces Ian Marter as the very old-fashioned naval doctor Harry Sullivan, immediately a wonderfully straight-laced foil for the daffy new Doctor.

“You may be a doctor, but I am the Doctor,” he informs Harry. “The definite article, you might say.” And with that, the programme is his. In a nice rerun of the earlier joke, there's a moment of horror at his new reflection, before he declares the nose to be “a definite improvement,” seemingly just to rile Pertwee, before another escape attempt in the TARDIS. We then get a particularly silly scene in which the Doctor tries on various costumes, before the Brigadier desperately tells him to stop, causing him to stick with the now legendary hat-and-scarf ensemble. Even as he rides in the Third Doctor's familiar yellow car, Baker has completely superimposed himself on Pertwee's place in the series.

There's quite a decent plot going on behind all this, with the eponymous robot running amok at the orders of a sinister meritocratic organisation fronted by a Think Tank. Sarah Jane investigates this as a journalist after the Brigadier unwisely divulges classified information to her. The Robot, a hulking silver giant (Michael Kilgariff), is torn between his prime directive to do no harm, and his orders to take out undesirables for the Think Tank. The robot's missions are effectively shown in a special robot's eye-view, complete with a background of blinks and bleeps. There's a lot of CSO (what we now call green screen), something that had become a ubiquitous part of the programme's repertoire over the Pertwee era, which culminates in the robot growing to King Kong proportion and running completely out of control. There's some fun undercover shenanigans and lots of double-crossing for the grown-ups, and silly robot histrionics for the kids. Or maybe it's the other way round. As the Doctor says, “There's no point being grown-up if you can't be childish sometimes.” The serial ends with the Doctor and Sarah essentially abducting Harry and going off in the TARDIS, effectively ending the UNIT-dominated era of Doctor Who save for occasional trips back to alien-menaced Great Britain.

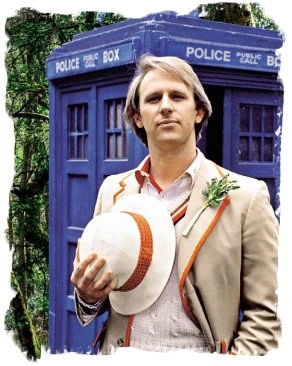

Peter Davison: Castrovalva (January 1982)

Doctor Who, and indeed, television, had moved on a great deal during Tom Baker's tenure. The series moved into the eighties with season eighteen, with a revamped look, a new title sequence, and a new, up tempo arrangement of the theme tune. The producer of the series was now John Nathan-Turner, who would stay on in the role until the end of the decade, while Christopher Bidmead worked as script editor. They provided a new focus on high concept sci-fi storylines. This continued into the beginning of the nineteenth season, when Peter Davison took over as the Doctor. Bidmead provided the script, while Eric Saward took over as script editor.

If Baker and Troughton had a tough time taking over as the Doctor, Davison was really in for a challenge. Baker had become the single most popular Doctor ever, remaining in the role for seven years and becoming so synonymous with the character than even today most people still think of him when they hear the name Doctor Who. Nathan-Turner cast Davison as an already well-established and popular actor, known for All Creatures Great and Small, Sink or Swim and Holding the Fort. Both the performance and the writing of the Fifth Doctor were a world away from the commanding, seemingly indestructible Fourth. Physically younger, less resilient, and more reliant on his companions, the Fifth Doctor was a marked change to the Fourth.

Castrovalva – named for an Escher print, itself named for a village in Italy – is a story of two halves, the series now broadcast on two consecutive weekday evenings instead of its traditional Saturday night slot. The first two episodes see the Doctor struggling to cope with his regeneration, following his battle with the Master. The villainous Time Lord, originally played by Roger Delgado opposite Pertwee, was revived and revamped for the 1980s, now played with camp aplomb by Anthony Ainley. The opening episodes see the Doctor's young companions Tegan (Janet Fielding) and Nyssa (Sarah Sutton) drag him back to the TARDIS, while Adric (Matthew Waterhouse) is captured by the Master for his own nefarious use. While the TARDIS spirals back in time to the Big Bang in the Master's latest trap, the Doctor searches for the Zero Room – a safe environment to recuperate in – while he struggles to find himself.

“I'm the Doctor,” he says, “or will be if this regeneration works out.” It's disconcerting to see the Doctor so vulnerable. Swamped by Baker's costume, he literally unravels, discarding it piece by piece and unspooling the iconic scarf. As he wanders the corridors, forgetting his friends’ names, he runs through aspects of the previous Doctors' personalities. Davison gives some canny impersonations of his predecessors, and it's a clever way of reassuring viewers that this is the same character they've watched all these years. It's also an indication of how wrapped up in its own past the series will become during the eighties. The Doctor gains some measure of his own personality when he stumbles on the TARDIS' cricket pavilion, picking up his sporty new costume. He's not quite happy with himself though. “That's the problem with regeneration,” he says, seeing his reflection, “you never quite know what you're going to get.” It's only in the Zero Room itself that the Doctor seems in command of himself, and this doesn't last long.

Escaping the imminent destruction of the TARDIS requires the jettisoning of various rooms, including the Zero Room, leaving the Doctor vulnerable once again. Nyssa and Tegan follow clues to take the TARDIS to Castrovalva, a tranquil idyll, which becomes the basis for the second half of the story. The story progresses slowly, with much of the third episode spent actually reaching Castrovalva proper. Once there, the Doctor begins his recovery, still very much piecing himself together. He can't even count to three without help. While he's a very fragile new version of the character, Davison's performance as the Doctor is captivating. The truth of Castrovalva becomes apparent, as like an Escher print it is folded over itself, “a space-time trap.” It's an ingenious concept for a sci-fi story, albeit perhaps a bit abstract for a new introduction to a series. The Master remains there, hidden in plain sight, and facing up to him seems to finally solidify the Doctor's new persona.

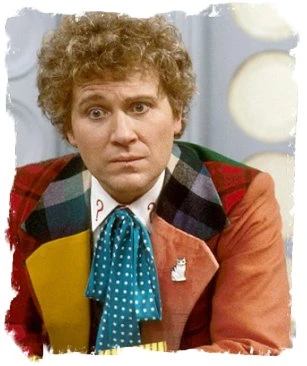

Colin Baker: The Twin Dilemma (March 1984)

1980s would see the roster of Doctors turn over rather more quickly than in the past, and it was only a little over two years before Davison left the role to be replaced by Colin Baker. The production team remained largely the same as before, with Nathan-Turner deciding that the new Doctor would debut at the end of the season rather than the beginning of the next, to ensure viewer loyalty over the gap. Working against this idea, though, was the notion to make the new Doctor especially difficult and unlikeable, all the more baffling since Nathan-Turner anecdotally cast Baker due to his extremely charismatic turn at a party they had both attended. In contrast to Davison, who was known for likeable characters and given a pleasantly characterised Doctor, Baker was best known as the unpleasant Paul Merroney in the 1970s series The Brothers and was presented with a Doctor written deliberately as overbearing, arrogant and even cruel.

By now, viewers were accustomed to the idea of the Doctor changing form every so often, so to focus more than ever on the after-effects of regeneration was potentially a good idea. However, by making the new Doctor so unstable, any good will for the new iteration of the character was lost. Initially, the Sixth Doctor was hugely pleased with his new self, congratulating himself on his appearance and dismissing his former self. His companion Peri, played by Nicola Bryant, was horrified by the transformation, but allowed herself to try to get used to the new Doctor. The first episode of The Twin Dilemma – credited to Andrew Steven but heavily rewritten by Eric Saward – included a wardrobe scene. This, set within the TARDIS among a clutter of recognisable costumes from years gone by, would become something of a tradition for these transitions. During this scene, though, once the Doctor had chosen his new multicoloured outfit – designed to be as tasteless as possible – he begins to suffer from post-regenerative instability, expressed as extremes of fear, anger and even violence. While the Doctor gets ahold of himself gradually over the first two episodes of the four-parter, it's hard to see many viewers wanting to stay on long enough to see the character settle down.

It's a shame, since Baker and Bryant were both quite capable of giving decent performances as their characters, but they are visibly struggling to work with the material they're given. The Twin Dilemma isn't well-made in any aspect. The serial begins by introducing two obnoxious teenagers with speech impediments – rather cruelly given the names Romulus and Remus – and only gets worse from there. A deeply nonsensical plot involving an alien slug who wants to spread its eggs throughout the universe unravels from there. Kevin McNally plays Hugo Lang, a sort of space policeman who acts as a rather sweet one-off companion, and the distinguished Maurice Denham gives as dignified performance as possible as Azmael, an old Time Lord friend of the Doctor's, but none of the cast can hold up the story. Even the blurb on the BBC's official DVD release seems apologetic about it.

While it's a guilty pleasure, Colin Baker's first serial can't be called anything approaching good, and unfortunately much of his tenure would be saddled with similar poor creative decisions. In spite of some decent stories during his brief tenure, Baker's era of the series is generally considered the poorest and it lost viewers. Baker would be unjustly blamed for much of this and was dismissed from the role, understandably refusing to return for a one-off regeneration story. This would make his successor's introduction something of a challenge.

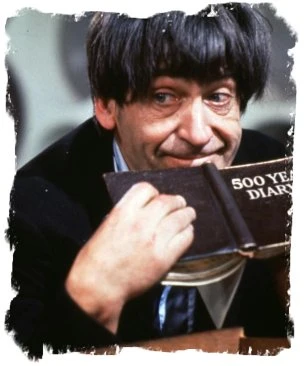

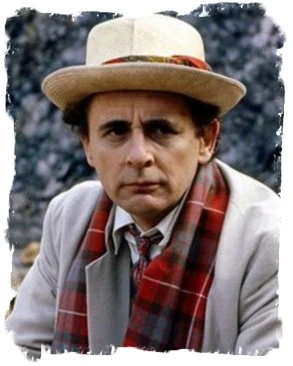

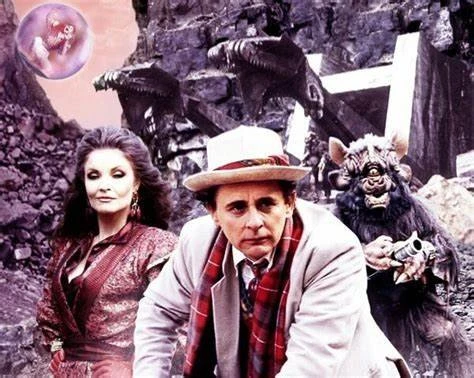

Sylvester McCoy: Time and the Rani (September 1987)

Doctor Who's twenty-fourth season was rushed into production after a chaotic period on the programme left the series without a star or a script editor. John Nathan-Turner, although wanting to move on, was compelled to continue as producer, and eventually cast actor and stage stunt performer Sylvester McCoy as the Seventh Doctor, while employing the young Andrew Cartmel as the script editor. Cartmel would stamp out a new era of the series with a number of brand new writers, but without suitable scripts lined up for the new season and time running out, Nathan-Turner employed Pip and Jane Baker, writers of several scripts for Colin Baker's Doctor, to pen the season opener.

The result is very much a holdover from the Sixth Doctor era, and not one of the better examples, with a contrived and incoherent story which sees villainous Time Lady the Rani abduct geniuses from throughout history to create a giant brain for an evil experiment. It's a children's telly adventure serial with little substance, but it holds together rather better than the previous Doctor's introduction. McCoy benefits from a distinct new style of production, with a glitzy and garish new title sequence with a jolly new theme arrangement, immediately setting this as a new era of the show. Before the titles, though, we get a cold open, in which the TARDIS is attacked and forced onto an alien planet, in a colourful and rather effectively rendered sequence. The Rani, played with camp confidence by Dynasty's Kate O'Mara strides onto the TARDIS with her alien henchmen the Tetraps, and gives the unforgettable line: “Leave the girl, it's the man I want.” Unfortunately it's all let down by a botched regeneration, where a prone McCoy wearing Baker's costume is turned onto his back, his face obscured by a swirling video effect and a blonde wig, before resolving into the clarity.

What was once an ingenious and surprising part of Doctor Who's inventiveness was now an awkward piece of obligatory business that had to be put out the way with the minimum of fuss. In fairness, it's hard to see how else a regeneration could be shown without Baker returning, but then perhaps it would have been better to forego it altogether. It's not even clear why the Doctor regenerates (inspiring both licensed and fan stories to explain it away).

Once the story proper starts, the Doctor is surprisingly back on his feet very quickly, a marked contrast to the increasingly drawn out post-regenerative trauma he's suffered in previous introductions. However, the Rani then injects him with something to give him amnesia, pretends to be his companion Mel and convinces him that it's his experiment all along. The real Mel, played by Bonnie Langford, is lost elsewhere on the planet, and harsh as it sounds, O'Mara is rather better in the part than the Langford is. The Doctor continues to run around in Baker's oversized costume – seeing the Doctor in his predecessor's clothes is a favourite part of any regeneration story – before returning to the TARDIS for a long wardrobe sequence which sees him try on various silly costumes and previous Doctors' outfits, calling back to both Bakers' debut stories. In the end, the new Doctor settles on an outfit that, while fairly ridiculous, is at least an improvement on his predecessor's.

In stark contrast to the Sixth Doctor, the Seventh is utterly unhappy with his new self, concerned he'll be lumbered with an unpleasant new persona. This actually makes him rather more likeable than the boisterously egotistic Sixth Doctor. The new Doctor is something of a grouchy professor here, but also a comedic character, mixing his metaphors and playing the spoons (not that unlike Patrick Troughton's playing of the recorder, and, I'd say, less irritating). His gurning and pratfalling is certainly silly, and McCoy is perhaps the weakest actor to play the part, but he's entertaining in a childish way.

Once he stops screaming at aliens and is finally allowed to meet the new Doctor, even Mel settles down. Interestingly, she says she “knows all about regeneration,” so at least the Doctor was sensible enough to forewarn her, but even so, she struggles to take in just how different the new incarnation is. The scenes with the Doctor establishing his new personality is by far the most effective of the serial, with the rest mostly involving yellow lizard-people locking Einstein in a cabinet while bat monsters chase them around. There's a good cast hidden in here, with Wanda Ventham and Donald Pickering doing their best to retain their dignity as alien Lakertyans, but it's hard going. Still, it all looks very pretty and it's quite possible to enjoy it if you switch your brain off.

Doctor Who would quickly become more experimental under Cartmel's direction, leading to some of the best scripts in years for its last two seasons. However, by this stage viewing figures had waned considerably, and the programme was not renewed after its twenty-sixth season in 1989. There would, however, be two attempts to revive the series on television in the years to come, one of which would be rather more successful than the other.

Published on May 7th, 2020. Written by Daniel Tessier for Television Heaven.