Jacqueline Hill

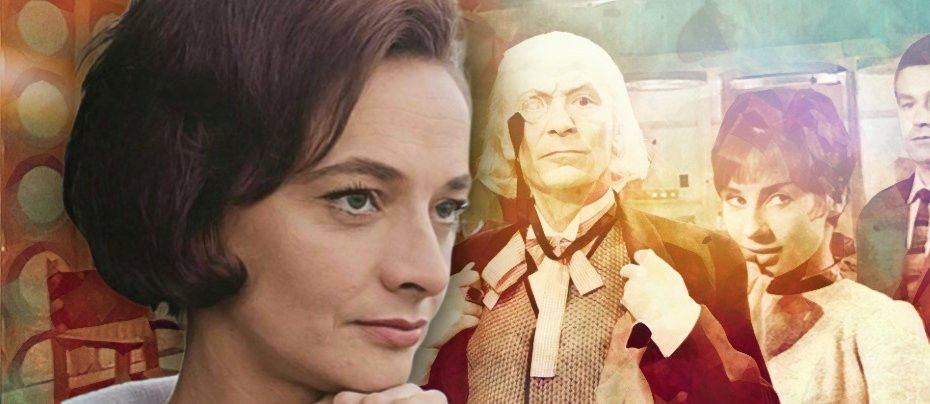

The importance of Jacqueline's character in Doctor Who cannot be overstated

Grace Jacqueline Hill was born in a narrow terraced house on Unity Place in Bournbrook, an industrial and residential area of southwest Birmingham in the district of Selly Oak, on 17 December 1929. Her parents, factory workers Grace and Arthur Hill, had - by all accounts - a tempestuous relationship that was always doomed to end in separation and divorce. Eventually, Grace abandoned the family leaving Arthur to bring up their two children, young Grace (who was almost always referred to by her middle name) and her younger brother Arthur Jr.. And although Grace only moved a short distance away, she rarely, if ever, visited her children again.

In late 1937, Arthur Snr left home on his bicycle to meet up with a female neighbour, and never returned. Whilst crossing an intersection the couple drove the tandem straight in front of a bus and Arthur died at the scene of the crash.

Although the children had a large extended family, nobody could agree who would take them in and for a time they found themselves on Parish Relief, which usually involved orphaned and deserted children being boarded out, if possible, at foster or children's homes and in some cases at boarding schools. Eventually, it was decided that Arthur's mother, Sarah and her second husband, Albert, would adopt the children. However, Albert was described as something of a tyrant and the children had an unhappy upbringing in his company.

At this time around 80% of children left school at age 14, most having only ever attended an all-age elementary school. Further education would come at a cost, and it was a price that Sarah and Albert were either unable or unwilling to pay for Jacqueline. The attitude at the time was in favour of boy’s education being more important as girls, it was felt, did not really need an education. As soon as Jacqueline turned 14 she was made to leave school and go to work. The money saved and the wages she brought in would support her brother's continued education.

Birmingham, an important industrial centre during the Second World War, prided itself on being replete with factories where planes, tanks and army vehicles rolled off the production lines. Many smaller workshops were involved in making items such as ammunition cases and grenades and there were firms producing saddles and packaging. So there was no shortage of employment opportunities for Jacqueline. But rather than working on a production line, she decided to apply for a job at the Cadbury's Bournville factory.

Bournville had long been one of the most sought-after places to work. In 1893, George Cadbury bought 120 acres of land at his own expense, to create a model village which would "alleviate the evils of modern, more cramped living conditions". By 1900, the estate included 313 cottages and houses set on 330 acres of land, and many more similar properties were built. The Cadburys, particularly concerned with the health and fitness of their British workforce, incorporated park and recreation areas into the Bournville village plans and encouraged swimming, walking and all forms of outdoor sports. Fourteen-year-old Jacqueline began work on Monday 7 February 1944 in the Wages Office.

Because she was under 18-years-of-age, Jacqueline would spend one day a week on compulsory study leave. She would study English, arithmetic, music and drama - and all at the company's expense whilst on full pay. And it was here that, over the next five years, her destiny would be determined.

At the age of sixteen, Jacqueline appeared in a production of Twelfth Night at Bournville's concert hall. The following year she was cast as Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice, a performance that drew the attention of the Birmingham Gazette. 'Jane Austen lovers would have no quarrel with Jacqueline Hill's interpretation', it reported. Over the next few years, Jacqueline continued to make her stage presence felt and was rewarded with a School Leaving Scholarship of £100 to fund a course at the Birmingham School of Speech and Training. Her Bournville managers were also openly encouraging her, and she began to gain further experience in Rep. By this time her heart was firmly set on an acting career and when she read about scholarships at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, she had no hesitation in applying even though her chances were slim as RADA, at that time, only awarded two scholarships a year. One to a male and another to a female would-be actor. Jacqueline won her place.

At RADA she began voice training and soon lost her provincial accent and also discovered that she could do a very convincing American one without the exaggerations common among British actors at the time. She made a good enough impression at RADA to win a part in the 1951 final-year performance intended to showcase the talent of upcoming actors to agents and producers. 1951 and 1952 were spent touring the country in Rep until she heard that the American actor and director Sam Wanamaker was auditioning for a play called The Shrike. Jacqueline went to the theatre where the auditions were taking place and sat at the back of the stalls waiting for her chance. When it came, she impressed Wanamaker with her convincing American accent and won a role of a psychiatric nurse. It was a small role, but after a provincial premiere in Brighton it arrived on the West End stage in February 1953. Unfortunately, the play was not received well by critics and audiences stayed away. It closed by the end of the next month.

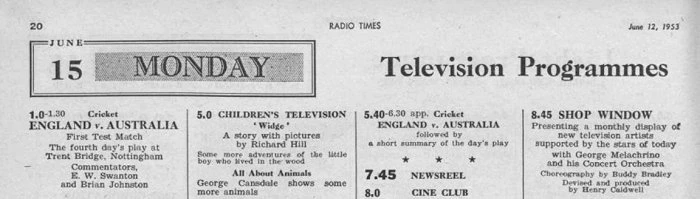

Undeterred, Jacqueline now began sending out notes to television drama producers informing them of her availability and her experience, hoping that a West End performer was more of a draw than a complete unknown. In fact, it was Sam Wanamaker who arranged for her television debut a few months after The Shrike closed.

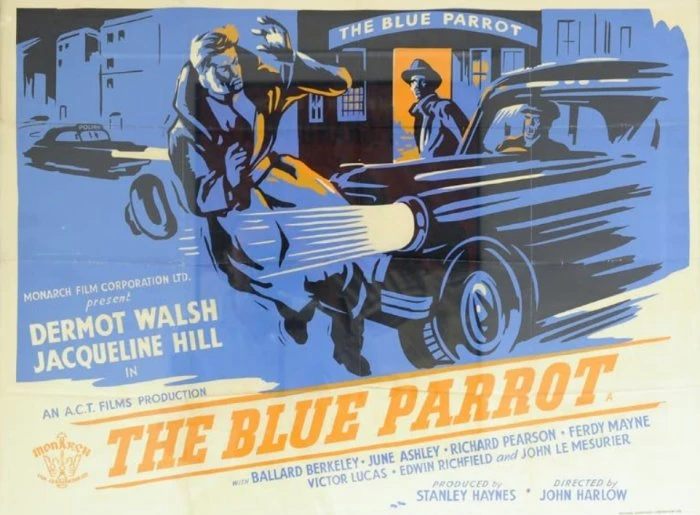

Wanamaker was invited by the BBC to showcase a scene from a play titled Golden Boy on their upcoming television show Shop Window. The programme only had a 15-minute timeslot but in that time Jacqueline managed to make quite an impression. As a result, she had a flurry of producers and agents calling her the morning after that transmission. Director John Harlow was one of them. He was about to start shooting a crime thriller, The Blue Parrot, at Nettlefold Studios and still hadn't cast the female lead. Although this was only going to be a b-feature, the chance of appearing on the big screen would be a great boost to Jacqueline's career. However, it didn't have the effect she hoped for.

In November, Jacqueline appeared in a children's adaptation of The Rose and the Ring (which also starred David McCallum) and in early 1954 she appeared in the teenage magazine show Teleclub, but other than that she wouldn't appear on television again until 1955. However, during that period she had met Canadian producer Alvin Rakoff, who she would eventually marry.

It was Rakoff who was instrumental in Jacqueline's return to our television screens. The Legend of Pepito a BBC Sunday-Night Theatre production which aired on 5 June, was produced by Rakoff and reunited Jacqueline with Sam Wanamaker. As with the two actors' previous collaboration, critics were unimpressed, although one critic did pick Jacqueline's performance for special praise by referencing her full TV debut and saying that, 'her phone may well be ringing again on Monday morning.'

Jacqueline's next BBC play was November's A Business of His Own which is set in a New York skyscraper and gave her the opportunity to use her American accent again. In it she plays Helen Gold, a young Jewish girl who has recently remarried. This time the critics were very much in favour of the production. Reginald Rose's play Three Empty Rooms was next - broadcast on 27 December 1955. But by now the BBC were facing stiff competition from the fledgling ITV network - and they were losing the ratings battle. Badly. Nevertheless, Jacqueline's career was going from strength to strength.

In 1957, Jacqueline appeared in her longest running series yet when she was cast as Carrie Dean, a character in the 6-part BBC series Joyous Errand, a mystery story about a woman (Ursula Howells) seeking the truth about her husband after his death. According to the Radio Times, 'Carrie is an extraordinary woman, rootless and with a gaiety that is all too easily discernible as desolation well disguised.' Again, Jacqueline got to use her American accent. But the series was beset with problems, not least of all the loss of its leading man half-way through. Peter Arne apparently walked out of the series after objecting to a script change. Kevin Stoney was drafted in to take over the role that Arne had vacated. After a promising start the critics abandoned the series quicker than its audience, although the Glasgow Herald had the last word: 'Dramatically last week ended away at the bottom of the class with the final instalment of Joyous Errand, a series so painfully artificial that it is a wonder only one member of the cast deserted.' Ouch!

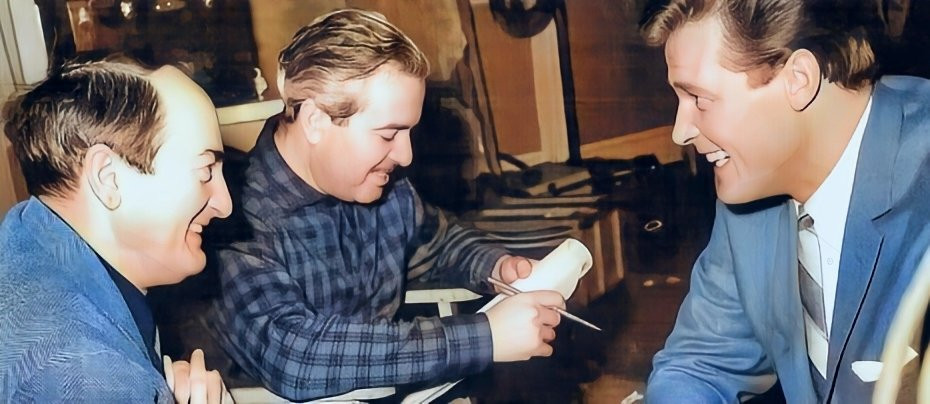

While Jacqueline's career continued at a steady, if not spectacular pace, in 1957 she did help to push another aspiring young actor into the spotlight. Alvin, who she was now living with, was producing a British version of the Rod Serling play Requiem for a Heavyweight. The story about a punch-drunk professional boxer had been a big hit on US television the year before with Jack Palance in the lead role. Alvin had secured Palance for the British version, but the star pulled out a week before production was to begin. Desperate to find a replacement, Alvin had tried everywhere to find an actor who could convince in the role of a fighter. It was Jacqueline who suggested an actor she had seen in South Pacific. "Have you thought of Sean?" she asked Alvin. In its critique of the play the Daily Mirror wrote, 'This lovable bonehead, played with quiet certainty by Sean Connery, was a fine piece of creative characterisation. He is star material if ever I saw it.'

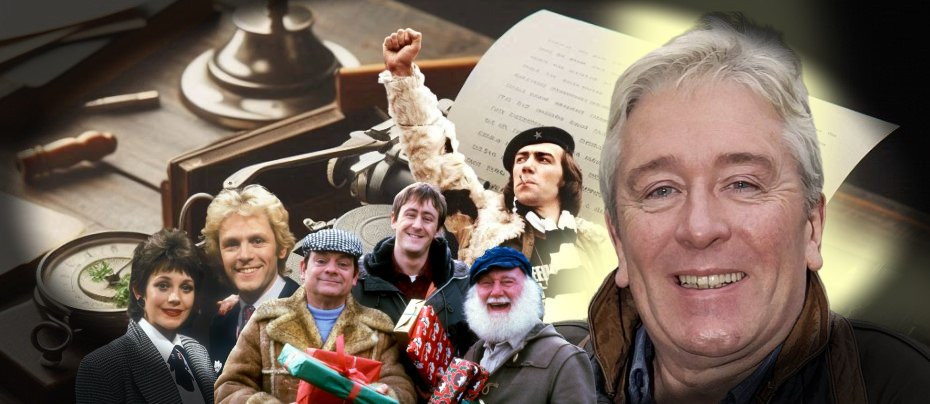

Jacqueline continued to pick up roles on television over the next few years, appearing in plays and making appearances in several popular series. She also got to practise some other accents other than American. She was Australian in an episode of The Flying Doctor in 1959 and a murderous French housewife in Maigret (The Trap) in 1962. She also got to do some science fiction in an episode of Out of This World (Medicine Show) about aliens with medicinal powers who had come to visit Earth. But it was another science fiction series the following year that would propel her to that of household name and secure her place in television history.

"I was at a party one evening and the usual bunch of friends were there," Jacqueline said in a rare interview for Doctor Who Magazine back in 1985. "I’d known Verity Lambert socially since she had joined the ABC television company for whom both my husband and myself had done some work. She was one of Sydney Newman’s proteges, and by this stage she had transferred with him to the BBC, where she had been asked to become a producer. Anyway, this party came at just the right point for me, because Verity was in the process of casting the regulars for her new television serial Doctor Who. We talked about it, and shortly afterwards, she offered me the part of Barbara Wright, which I was more than happy to accept.

“All I knew at first, all I was actually told, was that my character was a very learned history teacher and that I was there to represent the Earth point of view when we went back in time and did the occasional serial set in the past. I found that quite easy, as I liked history and those historical stories appealed to me anyway. Everything else I had to put in myself, and this meant taking it up with either Verity or the director concerned. I think there were times when I said, ‘Barbara wouldn’t say this or she wouldn’t do this’, and they were usually very good and listened to me on those points because I knew the character better than anybody else."

Although Doctor Who's female companions have the reputation of being 'screamers', Barbara Wright never fell into that category. "The good thing about Barbara was that because she was older than most of the girls since, the writers were more hesitant about making her look silly or scream too much. That side of things was largely left to Carole Ann Ford, which is why she left earlier than Bill Russell and myself."

The importance of Jacqueline's character in Doctor Who cannot be overstated. She was the first character to speak in the series, the first to enter the TARDIS, the first to encounter a Dalek, and the first to stand up to the Doctor in a story that changed the whole dynamic of the series. Up until The Brink of Disaster, the second of a two-parter set entirely on board the Ship, viewers were still not entirely clear if the Doctor was completely trustworthy. Was he merely a confused mad professor or was he hiding villainous intentions? Certainly, the way in which he kidnaps the two schoolteachers in the opening episode, how he picks up a rock to smash in the skull of a caveman in their first adventure and how he manipulates the situation in The Dead Planet so he can investigate the mysterious modern city, all point to the latter possibility. This is taken to further extremes in the Edge of Destruction where the Doctor accuses the school teachers of trying to sabotage the Ship and threatens to throw them off the TARDIS.

Up until that point Barbara and Ian (William Russell) are very much at the mercy of the Doctor. But when pushed to the edge, Barbra's tirade at the Doctor begins to level the relationship out: "How dare you! Do you realise you stupid old man that you'd have died in the cave of skulls if Ian hadn't made fire for you? And what about what we went through with the Daleks? Not just for us but for you and Susan too. And all because you tricked us in going down to the city. Accuse us? You ought to go down on your hands and knees and thank us. Gratitude's the last thing you'll ever have - or any sort of common sense either!"

It's a remarkable speech that Jacqueline pulls off excellently - delivered perfectly with emotion and authority. Then in the second part of the story, it's Barbara who saves the day by piecing together the clues that the TARDIS is giving the travellers all along, allowing the Doctor to save the Ship from total destruction. After that, all the travellers were on a more even footing. The Doctor has a newfound respect for the humans, and it becomes apparent that his previous attitude towards them was one of wariness and not subterfuge. Clever, compassionate and strong-willed, Barbara Wright very much reflected the true character of Jacqueline Hill. Her display of strong female independence, a rare sight on 1960s television, would not be out of place today.

Neither was Jacqueline ever noticeably sidelined in the stories. In fact, many stories put her centre stage of the action. Especially in the historical adventures. "I think I liked The Aztecs, and the one about the Crusaders, best. In The Aztecs I had the most magnificent headdress, which was terribly difficult to balance, but which looked superb and made me feel very regal. The story itself was extremely clever and it was a fascinating period. I suppose I liked it above all the others because that was the one in which Barbara was most important to the storyline. I liked The Crusades for similar reasons."

By the end of April 1965, Jacqueline had worked solidly on Doctor Who for over 18 months and decided that she had taken the character of Barbara Wright as far as possible. Her decision to leave the series coincided with William Russell's. "Everything that we wanted to do in the series had been accomplished and we felt, and I think Verity sneakingly agreed with us, that it was time for the series to try and see if it could do something new. As for the question of going together, well, it all just seemed to come together at the right time for both of us. I think it had always been felt that Ian and Barbara, who had this slightly romantic side to their relationship, should go together much as they came - back to the London they left." Their final adventure on board the TARDIS was The Chase.

Upon leaving the series both actors found themselves cast together again, appearing in Terence Rattigan's Separate Tables at the Leeds Grand Theatre. The draw for the public was to see the 'Stars of Doctor Who'. After that she took one more television role in a 1966 episode of No Hiding Place (You Never Can Tell Till You Try - tx 25 May), before taking an extended break from acting.

Jacqueline and Alvin had adopted two children and she wanted to concentrate on raising them. After her own personal experiences, shunted from place to place, a relatively loveless childhood and being forced to leave school early, it is completely understandable that she should want to ensure stability and a good education for the children. She spent a lot of the time with her good friend Ann Davies, who she had met on the second Doctor Who Dalek tale. Davies was married to the actor Richard Briers and they had children of a similar age. She also reunited with her brother, Arthur, who she had not been in contact with for some time. Their early life together had been a difficult one and there were some emotional obstacles to overcome. Eventually, the siblings and their families became much closer.

It was only when the children had grown up that Jacqueline's thoughts returned to acting. Perhaps she hadn't anticipated just how long she would be away when she turned her attention to the children, but it was now 1978. Her return to the screen came in an episode of the popular daytime drama series Crown Court, although she found there were not too many offers of work following that. Unlike today, 1970s television was a notoriously bare playground for women 'of a certain age'. Later that same year she landed the role of Lady Capulet in Romeo and Juliet, part of the BBC's prestige project to film the whole canon of William Shakespeare's plays for television. Shortly after that production Jacqueline was diagnosed with breast cancer.

It was another two years before she appeared on screen again. She was in remission from her cancer when she appeared in Meglos, the 1980 Tom Baker story in Doctor Who. "We did Meglos in different studios, and of course television had moved on in leaps and bounds so that the technique was completely different. The special effects were a lot more dominant. It was recorded entirely out of order and there was nobody working on the story who could remember as far back as me - which was something of a humbling experience. I did enjoy it very much though, mainly because the part I played was so very different to the calm and unflappable Barbara. It was a happy reunion with a show that was really only the same show by name alone." It was another first for Jacqueline. The first time a regular Doctor Who character returned to the series as an entirely different one.

Jacqueline's next role was in an episode of the BBC medical series Angels in 1982, followed by two roles in Tales of the Unexpected. Her final role was in Paradise Postponed (1986), a Euston Films Production for Thames Television. But soon after she was diagnosed with bone cancer which was detected after a fall which cracked her sternum.

Jacqueline Hill passed away on 18 February 1993, aged 63 years, having fought her disease bravely to the very end. Always a pleasure to watch, Jacqueline’s courage and independence ensured that from an impoverished and painful beginning, she rose to become a hugely talented actress whose resilience, generosity and kindness was much admired by her contemporaries. The fact that almost 60 years after Doctor Who first materialised on our screens, the BBC is preparing to broadcast, in November 2023, the 60th-anniversary episode of the ongoing series, and that fandom, in all its glory, continues to look back with love and affection on the series’ formative years, means that her legacy has been cast as a vital piece of television history.

Marc Saul - December 2022

Published on November 10th, 2023. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.