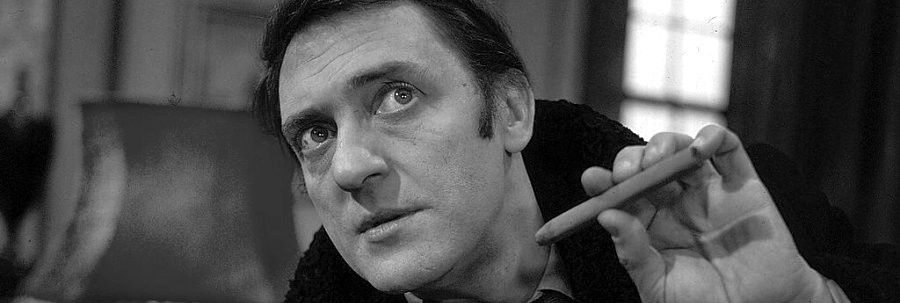

Harry H. Corbett

Born on 28th February, 1925, in Rangoon, Burma, the son of a British Army officer, Harry Corbett was only three when his mother died and he was sent back to England to be raised by an aunt in Wythenshawe, Manchester. Corbett first showed an interest in the theatre when, as a child, he was taken to the Manchester Opera House to see the comedian Leslie Henson.

"I used to spend many a glorious hour in the dear old lovable Coronation Cinema in Wythenshawe. It was a dream palace. I was reared on those marvellous films of the thirties. I idolised all and everything and that's where the spark first flew off the forge, I suppose." - Harry H. Corbett (speaking in 1967).

During the Second World War he served in the Royal Marines but it was soon apparent that he would never become a career soldier:

"I thought the entire set-up was wonderful. But it was just that I was completely miscast. I couldn't really believe it was all happening. I could march perfectly well with a rifle and all but when the band started to play it was all so idiotic I'd curl up with laughter and this did not seem to be appreciated. I was as keen as most to get out of uniform after the war. Me as an Armed Force was a bit comical anyway. I think this was mutually appreciated and eventually the day dawned when it was all over. They pressed 60 "nicker" into my grubby hand and pushed me gently out into the real world."

Following his discharge, Corbett trained as a radiographer, but gave it up (later claiming this was because he couldn't afford to pay for the long training).

"I wanted to be a doctor at one time. Fancied myself very strongly as a do-gooding type healer of the sick. But, of course, it's a long and expensive business and I didn't have the money or the brains to compensate for not having the money. I also wanted to be an actor. So there I was, out in civvy street again. Out of one mob and into another mob and the only difference was the shape of the uniform. But although there was nothing about me that was important I felt great personal happiness. I owned nothing yet the world belonged to me. Great days..."

A series of dead-end jobs ensued; grocer's delivery boy, plumber, male nurse and a car sprayer.

"I would take job after job as the mood struck me. I built prefabs, stacked timber, made electric switches. I changed with the weather. When the sun came out I burst out with it. When it got cold I pulled a roof in over me somewhere and eventually I became a partner in a two-man car spraying business.

"I worked hard at this, because I was the half-boss. There was only me and this other fellow and there was money in it. I sprayed and sprayed and sprayed. I sprayed when the dawn came up, when night fell-and when there wasn't a single car around-I still sprayed. From this developed my colourful language, or at least my colourful language developed when the lease ran out. We were making a lot of money at the time. However, to wash away the spray I would occasionally toddle off to a pub or two. And there I met some of the real characters of the world. Pub musicians. And they were extremely valuable to me when my highly lucrative half-business folded because one of them suggested I had a go at the local drama company. They knew I was mad keen on acting. I just needed the right shove at the right time."

Corbett joined the Chorlton Repertory Company (where he started, almost quite literally, at the bottom; "I can remember playing the front legs of a cow in a pantomime"). His first real role was as a detective, and he was paid £2.10s (£2.50) a week. From these humble beginnings he graduated to Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop at London's Stratford East, performing classical works from Shakespeare to Ibsen, all the while gaining a reputation as a rising star. Around this time he added the 'H' to his name to avoid confusion with child entertainer and Sooty creator Harry Corbett. When asked in future what the 'H' actually stood for he told everyone it was for "h'anything."

In the late 1950s Corbett began to pick up regular TV roles in a number of productions such as The Adventures of Robin Hood, but most notably in the classic anthology series Armchair Theatre, the first of these as a condemned murderer in The Last Mile (broadcast 03/11/1957) was followed by six more by 1959. He played an Italian tradesman in the comedy A Gust of Wind (23/02/1958), a cockney trader in Eugene O'Neil's drama Emperor Jones (30/03/1958), a confederate soldier in the American civil war drama The Sentry (04/01/1959), a theatrical producer in the drama The Bird, The Bear and the Actress (08/03/1959), a character called Charlie Panetti in The Jukebox in which he co-starred with Alan Bates and Miriam Karlin (17/04/1959), and George Albert in a drama The Shadow of the Ruthless (26/04/1959) which also starred Anthony Quayle, Charles Gray, John Barron and David McCallum. All parts that showed his great versatility and prompted one writer to describe him as "the English Marlon Brando."

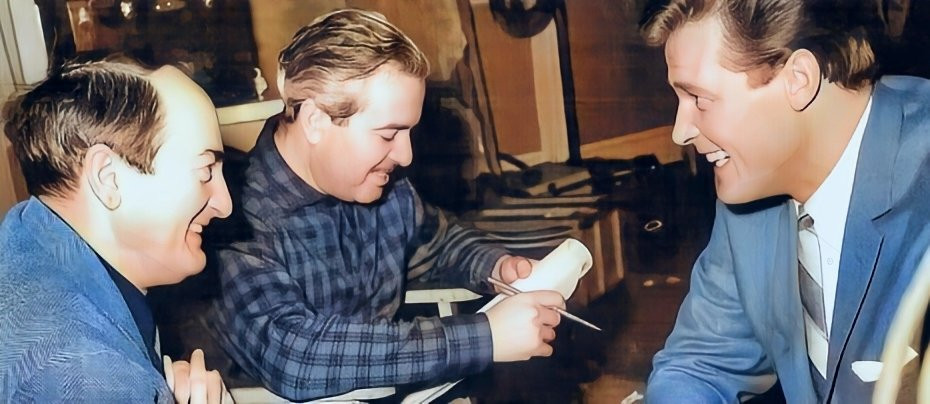

In or around 1960 Corbett met the scriptwriters Ray Galton and Alan Simpson who had great success writing the classic comedy series Hancock. "I had met Galton and Simpson and told them how much I admired their work, and I really did," he later recalled. "I said to them if they ever felt I could work with them, then..." Galton and Simpson remembered the conversation and when in 1961 they were writing a half hour one-off sitcom called The Offer for their BBC series Comedy Playhouse, Corbett was the first actor they thought of to play the part of Harold Steptoe, a rag-and-bone man with pretentiously overblown but ultimately doomed dreams of escaping his resolutely low brow father (Wilfrid Brambell) in order to better himself.

"I never envisaged in a thousand years going into light entertainment," said Corbett. "I looked at what was on television and the only thing making any, I don't know, social comment was the Hancocks, the Eric Sykes, this kind of half hour comedy programme, you see. And ooh, I did envy them. Anyway, ...this thing about the rag and bone men thumped through the door. I read it, and immediately wired back - 'delicious, delighted, can't wait to work on it."

During rehearsals for 'The Offer' Tom Sloan, the head of Light Entertainment at the BBC saw that what Galton and Simpson had written had the making of a full-blown hit comedy series, but the writers themselves didn't want to commit to one. Having just done a ten-year stint on Hancock the last thing they wanted was to get tied down to another situation comedy. In spite of the fact that the boys declined the offer, Tom Sloan was convinced they would change their mind. He kept on at them throughout the rest of the Comedy Playhouse series until eventually they said they'd only do it if Wilfrid Brambell and Harry H Corbett agreed to do it, too. Ray Galton says he never thought they would-but when it was offered to the two actors they both jumped at the chance to make another five episodes.

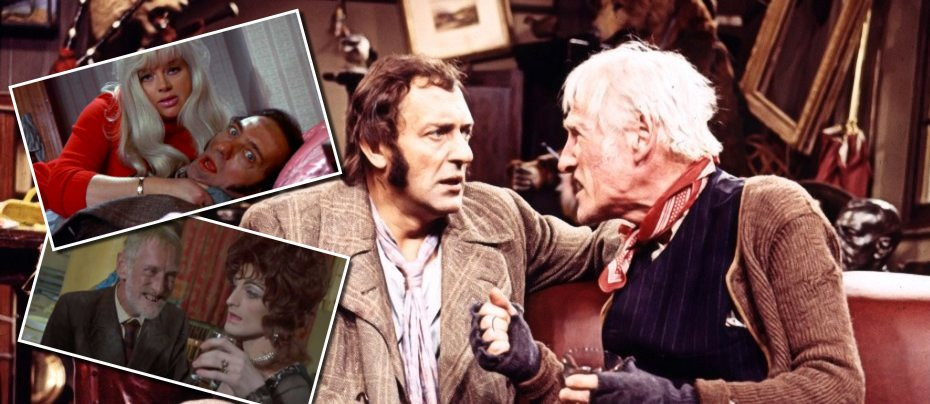

By the time the series was halfway through transmission Galton and Simpson had gone on holiday to Spain. After a few days away they were unexpectedly joined by Corbett, who told them that the show was a massive success and the BBC was already keen for a further series of six episodes. The series won the Writers' Guild Award in 1962 and 1963. With viewing figures of well over 20 million, Steptoe and Son established itself in the nation's heart and consciousness. The success of the series led to Corbett getting work in a variety of films including Ladies Who Do, The Bargee, Rattle of a Simple Man, What A Crazy World, The Sandwich Man and Carry On Screaming. But increasingly his public image became more and more associated with that of Harold Steptoe and he found it difficult to break away from the character.

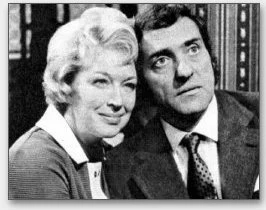

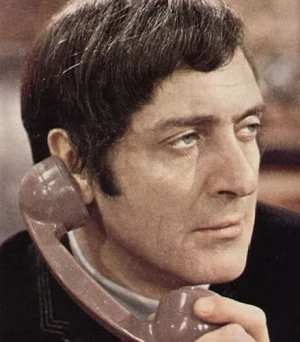

By 1967, it seemed as though Steptoe and Son had reached a conclusion, and the BBC repeated almost every episode of the four seasons 1962 to 1965. The format sold extensively abroad and the scripts were adapted in many languages. Corbett made an ITV series called Mr Aitch written by Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais. However, the series failed to take off and only one season of 15 episodes was made, going out between January and April and after 9pm on a Friday night. In 1969 he tried once more to break away from the Steptoe character by making The Best Things in Life starring alongside June Whitfield. In this series Corbett played a cockney spiv called Alfred Wilcox, a salesman who lives by his wits and tries to get to the top of his profession by taking a series of shortcuts, only to find at each turn his plan is thwarted by his own over ambitiousness. The series did a little better, lasting two seasons (the second of which was shot in colour), but it didn't bring the success he hoped for and when it finished, in 1970, the BBC offered him the chance to return to the character that had so frustratingly typecast him. With few alternatives on offer Corbett reluctantly accepted.

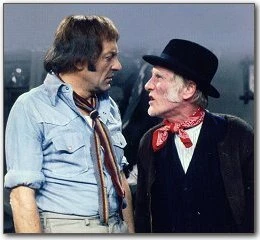

The new colour episodes of Steptoe and Son produced some of its most classic episodes. In 1972 Steptoe and Son went to the big screen. The film was moderately successful - enough for a sequel to be made the following year. Steptoe and Son Ride Again was not as funny as the first and the two rag and bone men seemed to suffer a similar fate to many half hour sitcom characters that were transferred to the silver screen.

The last episode of Steptoe and Son was the 1974 Christmas special. Following that there were not many offers of work and Corbett was rarely seen on television for the next 3 years. In 1976, his contribution to drama was recognised by the Queen with an OBE. In 1977, desperate for work and against his better judgement he agreed to a theatre tour of Australia to do a stage version of Steptoe and Son, but this proved to be an unhappy affair, in part due to Wilfrid Brambell's continuing battle with alcoholism which also caused him to frequently forget his lines. The pair did finally work again in 1981 in a short television commercial for the Kenco coffee brand.

In 1979 Corbett suffered a heart attack but it didn't stop him from appearing in pantomime at the Churchill Theatre, Bromley, just two days after being discharged from hospital. He made the occasional appearance as a guest star in a number of TV shows such as Potter and Shoestring and then in 1979, Thames TV offered him a 6-part comedy series entitled Grundy in which he co-starred with Lynda Baron, playing a newsagent with a puritanical streak, constantly speaking out about falling moral standards and the permissive society. The series transmission was delayed due to an ITV strike and was finally broadcast in 1980. It was the last sitcom in which Harry H. Corbett starred and it did nothing to enhance his reputation.

Harry H. Corbett's final acting role was in a 1982 episode of the Anglia Television anthology drama series Tales of the Unexpected, in which he played a man who planned to tunnel into a bank, only to have forgotten that the following day was a Bank Holiday Monday and there would be no money in the vaults. On 21st March 1982 he suffered a second, and this time fatal, heart attack. He was only 57.

In more recent years, Corbett and Brambell's relationship has become the subject of great interest. During their years of performing together there were a number of minor irritations or disagreements and they rarely socialised together. However, this was much exaggerated by a Channel 4 documentary film made in 2002 on the duo's off-screen life, titled: When Steptoe Met Son, in which it was stated that the two men detested each other and were barely on speaking terms outside of the programme. In preparation for the documentary, a researcher for Channel 4 went to see the two men who probably knew Corbett and Brambell the best; Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, and told them she wanted them to 'dish the dirt' on the two actors. Galton and Simpson told her they were not interested in this type of venture. When the researcher finished interviewing them, she apparently went back to her bosses who said, "this is all very nice, but it's not what we want." So the researcher went back to Galton and Simpson and told them they'd agreed to tone it down. The boys relented and allowed themselves to be interviewed. "Then we saw it, and of course they made it as scandalous as possible," said Ray Galton. "We did a follow up interview with one of the papers afterwards and they refused to print it. They said 'that's no good to us, there's no scandal.'"

The Curse of Steptoe a BBC Four production was broadcast on 19 March 2008 as part of a season of dramas under the umbrella title The Curse of Comedy. In it, Jason Isaacs played Harry H Corbett and Phil Davis was Wilfrid Brambell. The drama, based upon the actors' on-and-off screen relationship during the making of Steptoe and Son was probably a lot closer to the truth. The production also concentrated on what Corbett saw as the bitter demise of what was once a promising classical career and the break-down of his first marriage to comic actress Sheila Steafel and his marriage to Maureen Blott (who gave birth to his two children).

In 1969 he spoke candidly about his relationships with women:

"I take marriage seriously but it's a bit of a burden to free enterprise. And if you don't want to get hot, stay out of the kitchen, I say. There is a sense in which every man is a bachelor, hugging his independence and never giving it up without further hankering for it. So you must be dead certain that marriage is going to provide some pretty hefty and permanent compensations. I don't believe in romantic love. That eternity bit. I think you feel it when you're about 13, then it wears away with the acne. But I've a great urge for strong temporary attachments. The trouble with women is they think in terms of centuries. I tend to look ahead just a couple of months. When I say 'forever,' I tend to mean 'till Christmas.' They think we're planning to go hand-in-hand for our pensions."

One of the country's earliest exponents of 'method' acting, Corbett would draw on his own emotions, memories, and experiences in order to 'get under the character's skin' and replicate real-life emotional conditions under which the character he is playing operates. This way he felt he was able to create a life-like, realistic performance. He once said, "Harold is not me, Harold only exists on paper." But the longer he played the character the less convincing that claim became. That is why some of his best performances came in the later Steptoe episodes. It wasn't life imitating art but vice-versa. By then it is suggested that Corbett felt as helpless as Harold, forever trapped in a junkyard in Totters Lane. Galton and Simpson knew it, and the 1972 episode The Desperate Hours could almost have been (and probably was) written as much about Harry H. Corbett as it was about Harold Steptoe.

This episode best illustrated Harold's pathetic plight, when two escaped convicts break into the Steptoe home looking for food and money. Both escapees are mirror images of Harold and Albert with the younger one (Johnny) being thwarted and constantly held back in his ambitions by his older and dependant partner in crime (Frank). Harold, seeing a reflection of his own predicament, makes a heartfelt plea for Johnny to abandon Frank in order to give himself a chance of escape, and even ends up begging Johnny "take me with you," preferring a life on the run to being trapped in his junkyard. But when it comes to the crunch, when he has his destiny in his own hands, Harold can't bring himself to leave his father. There is a sense of hopelessness throughout the whole story, culminating in Harold's decision to stay within this perverse comfort zone of familiar surroundings - where life is safe and without risks. Like all great comedy, The Desperate Hours is as tragic as it is funny. No wonder one critic wrote of the series "(the show) virtually obliterates the division between comedy and drama." In this case it may well have obliterated the division between fiction and real life.

Harry H. Corbett once said of Harold Steptoe; "I like the part because the man I'm playing is a failure-and failures are often of more interest in life than successes. I think there's a bit of everyone in Harold. Most of us try to put on an act, often behave in a way that's foreign to us. Harold makes fumbling attempts to 'get culture' by reading or listening to highbrow records, by dragging his father to exclusive restaurants and foreign films. He doesn't really succeed in kidding anyone, and somehow his failure is complete and pathetic." In making this assessment of his alter ego it is hard to escape the possibility that Corbett was drawing a parallel to his own professional career. Here was a performer who was initially told by friends and critics that he had the makings of a great classical actor. But, due to a remarkable performance, an innate understanding of the character he was portraying and the instant empathy the audience felt with that character, he became forever rooted in the public consciousness as Harold Steptoe.

"He has his dreams all day, and so do we." Said Corbett of Harold. "It's in all of us and we never lose it. And he's a man in the grip of that terrible dilemma - how long do you stand by your duties and let life slip away from you?" Is that how he felt of his own career? If so, Harrry H. Corbett did himself a great injustice. What he bought to the role of Harold Steptoe was great dramatic pathos, creating a character who struck a chord with the audience in a way that no sitcom character had ever done before. Galton and Simpson's Steptoe and Son changed the sitcom genre forever more, but without Corbett the series would have had far less impact. His was one of the great dramatic/comedic character interpretations of all time - equal to anything he could have created from Shakespeare's works.

"One thing that frightens me-when people ask me to explain my success." He said. "For once you've pinned down the formula, you're finished. After Harold, the junk man, had gone no one would take me seriously. In a movie I was in with Edward G. Robinson, 'Sammy Going South', I was supposed to be a devil, and they just fell about with hilarity. I haven't tried villainy since."

However, to many people there is nothing to indicate that Harry H. Corbett compared the fate of Harold Steptoe to that of his own and neither is there much evidence to suggest that he despised his television character. "Success has meant that people listen to me a bit more. It's the money that does that. You look at two chaps in an office, one earning 50 quid and another 30. It's the bloke on 50 nicker who's going to get listened to. Yes, I've developed quite a bit of admiration for the chaps on the top of the heap. They've got the power. There may be a lot of idiots up there, too, but their voice is louder than anyone else's. To some extent, money has bought me that sort of freedom." But there were hints that this freedom came at a price. "After 'Steptoe' became a success I had to take taxis. I was denied the fundamental right of every Englishman. The right to travel on buses and the tube and keep himself to himself."

The closest the viewing public ever got to seeing the real Harry H was, according to the man himself, in his 1967 TV series Mr. Aitch.

"Mr. Aitch is really an extension of part of me. With Mr. Aitch I feel I've reproduced a character which has been boiling up in my mind for a long time now. Most of my life I have been lucky. I've not always had the money, but I have always been able to act out any part I want to play, whether it's professional on stage or before a real camera; or what passes for real life. And this is probably where Mr. Aitch and Harry H. Corbett come closest together: we are both dedicated to slaving ourselves to death-just so we can be lazy..."

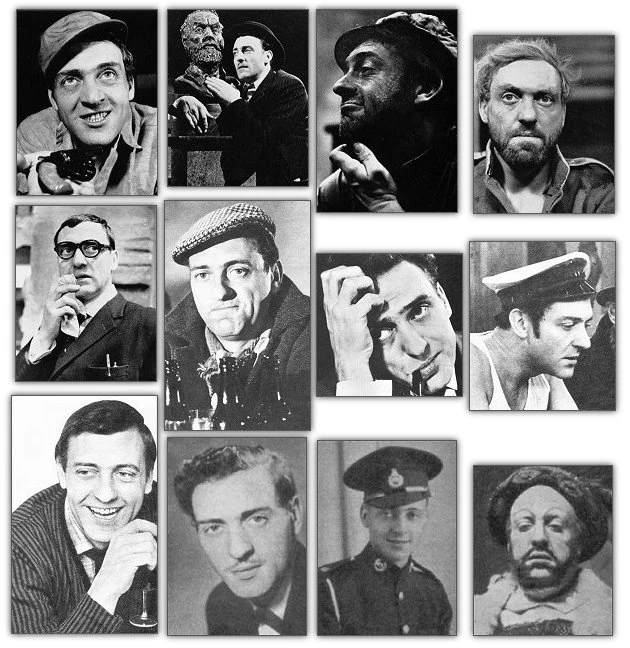

Harry H. Corbett as...

(Left to right top row) Condemned murderer in 'The Last Mile' | Italian tradesman in 'A Gust of Wind' | Cockney Trader in 'Emperor Jones' | Confederate Soldier in 'The Sentry' (middle row) Theatrical producer in 'The Bird, The Bear and The Actress' | Joe Brown's father in 'What A Crazy World' | Property Man in 'Ladies Who Do' | Hemel Pike in 'The Bargee' (bottom row) Himself | In the early days of Rep | In the Royal Marines | Henry Vlll

The Curse of Steptoe

Following The Curse of Steptoe the brother of Harry H Corbett's late second wife, Maureen Blott, complained there were "numerous specific inaccuracies" in the drama. The BBC admitted it was wrong to join two bits of Corbett's life which happened years apart. However, they also claimed that most of the departures from ascertainable fact were "legitimate exercises of dramatic license in the context of a drama featuring living or well-remembered people".

The complaint was upheld on two points: That Maureen Blott's relationship with Corbett preceded, and might have contributed to, the breakdown of his first marriage to Sheila Steafel, whereas the chronology it had established did not support this. And where the drama gave the impression that the end of 'Steptoe and Son' was immediately preceded, if not precipitated, by the birth of Corbett's first child, whereas the two events were separated by eight years.

The BBC will not re-broadcast the programme without appropriate editing and content information.

The BBC did not, however, include any statement of the impression it gave of Corbett's relationship with Wilfrid Brambell or his supposed feelings towards the Harold Steptoe character.

Published on February 20th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus (March 25th/April 19th/31st July 2008) Harry H. Corbett's own words in blockquotes taken from several TV Times articles, 1967 & 1969 for Television Heaven.