Steptoe and Son: The Offer

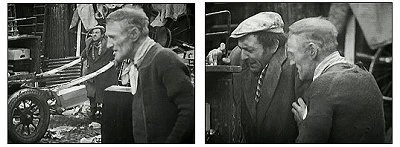

In 1961 Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, British television's most celebrated and prolific comedy scriptwriters, were presented with the opportunity to make their own series of one-off, half hour plays. The title for the series was Comedy Playhouse. The fourth offering in the series was a two handed dialogue between rag and bone men in London's Shepherd's Bush. The show proved an instant success, recognized by both the viewing public and the powers that be at the BBC as something very special indeed. Cast in the lead roles were Harry H Corbett and Wilfrid Brambell. Two actors who were not previously associated with comedy. Below, author Robert Ross writes about how this one programme, called The Offer, broke new ground in situation comedy and became a television landmark and the sitcom by which every other must be judged.

This review is reproduced for Television Heaven from Robert Ross' book 'Steptoe and Son' with the author's permission.

The bleakness of the opening scene, with its pioneering use of rather murky location filming, and the exhaustion of the totter after a hard day's work contrast with the buoyancy of Ron Grainer's 'Old Ned' signature tune. And Corbett's weary performance is perfect. With the atmosphere of gloom and dejection already in place, the appearance of Brambell's wiry old man completes the picture, and provokes the initial burst of - albeit almost inaudible -querulous banter between the two. Brambell claims an iconic moment in television history as he closes the junkyard gates behind him. His action reveals the shabbily painted legend 'Steptoe and Son Scrap Merchants'. The two actors were an instant and perfect match. 'They seemed to click into place in the first show,' recalls Alan Simpson. 'And they stayed like that.' Wilfrid Brambell and Harry H. Corbett had performed on television together before, both appearing in the 1959 adaptation of Turgenev's 'Torrents of Spring', with Corbett in the juvenile lead as Sonny, and Brambell as Mr Connor. Speaking in 1967, Corbett recalled the making of Torrents of Spring:

We started with the idea of translating the story into contemporary life. Then we said, here's something that's usually done in a serial over a long period of time. But we wished to do it in a single play, get the essence of it. We'll call this the new television we wish to go for. So we more or less got hold of the content and bones of the thing, and threw them away; then we got everybody together in the room, improvised it, and we taped it. It was the beginning of what I believe I'm known for, working with cameras.

The actors' experience with each other is clearly at play in The Offer. The chemistry between Brambell and Corbett is evident from the very beginning. They have a split-second sense of each other's timing, inflections and dramatic pauses, and their partnership goes beyond simply the polish of immaculate rehearsal, into the realms of instinctive mutual awareness. This is all the more amazing given that no one at the time believed this to be anything other than a one-off encounter. The first exchange of the script is representative of what is to come: the tone is set by the resentment and discord caused by the generation gap. The old man, showing more concern for the horse than for his own flesh and blood, is vindictive, nit-picking and dissatisfied. Asserting his authority as the head of both the business and the family, he immediately voices his dismay at the shortage of brass and lead on the load. He attacks his offspring's lack of business sense and bemoans the next generation with a bile-ridden, 'What sort of totter are you?'

But Harold emerges from his apparent dejection with mischievous glee, and announces his piece of news - he has been offered another job. The old man is completely winded by this long-dreaded revelation: his son is leaving home. Harold enjoys the old man's reaction and plays on it throughout the episode using the threat of his escape to countermand the lack of respect and responsibility he suffers from his father. We gather almost from the beginning that the offer is insubstantial, possibly illusory, but for Harold it is a psychological lifeline, a last chance to get away while the going is reasonably good.

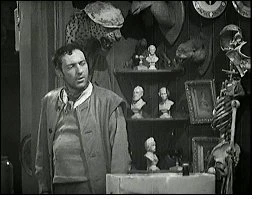

Harold's preoccupation with self-improvement is shown from the beginning, as he hazards ill-informed opinions on Chinese vases and porcelain. Throughout the episode, his aspiration to be a man of letters and his attachment to the precious symbols of sophistication that he has scraped together reveal his antecedents in Galton and Simpson's previous 'creation', Tony Hancock. But Corbett provokes pity rather than mockery as he boasts of the contents of his library only to reappear with a scant collection of four volumes neatly tied with string. All he has is his tattered chair, his half-completed wine collection and his pitiful four books. The fruits of his struggle for freedom, individuality and respectability are all loaded on to a handcart that is going nowhere.

Despite the clear similarities between Hancock and Corbett - in their expressive, mournful eyes, their vocal intonations and their flights of fantasy - Ray Galton maintains: 'We never consciously cast Harry in the wake of Hancock, but obviously the set-up was similar. The yearning for a better life, the aspirations above his station, all that sort of thing was very much like Hancock - that Sunday Times colour supplement knowledge of life.' 'And the old man was there to bring him down to earth,' continues Simpson. 'Just like Sid (James) did with Hancock. He was the voice of reality, the "with all these big ideas, you're being too grand" reasoning.' Throughout Steptoe, Harold often uses vintage Hancock terminology. There are suggestions of Hancock in the episode Upstairs, Downstairs, Upstairs, Downstairs, and in the film Steptoe and Son Rides Again Harold is even heard to mutter the immortal exclamation, 'Stone me!' Indeed, Alan Simpson reveals: 'At one time we were discussing a remake of all the Tony Hancock shows with Harry. That would have been after Steptoe had finished. Intriguing, isn't it?'

Writing in 1971, Galton and Simpson acknowledged their debt to their earlier series: 'Steptoe Junior and his father are in many ways an extension of the characters of Tony Hancock and Sidney James in the old Hancock's Half Hour series. The conflicts between the two sets of characters are also often based on common ground. However, the Steptoe series explores its characters in more depth.' Indeed, Corbett's moment of optimism in The Offer is nigh impossible to watch when the viewer knows beforehand that this will be as good as it gets for a long, long time.

Wilfrid Brambell also comes to his role with the essence of his character fully formed. The old man's ethos is in place from the first heart attack he fakes in order to get his own way. It is a trick in which, the script tells us, his son is already well versed. Indeed, as we become privy to the old man's miraculous recoveries and recurrent attacks as his son wanders in and out of the scene we get an immediate insight into his manipulative character. But Harold doesn't need to see the old man's sudden improvements and deteriorations. He's seen it all before. This knowledge of the Steptoes' strained, knowing relationship makes the characters familiar and appealing from the moment we meet them. Although we have never seen the characters before, the superb performances allow us to experience their humdrum existence as something that has been played and replayed many times. The occasional fumbled line or lost expression, as Brambell the actor is glimpsed behind the befuddled Albert Steptoe is endearing in itself.

Ray Galton admits: 'Later we did get very exasperated with Willie Brambell for stumbling on a line during a performance, as we couldn't go back and do it again unless it was a total disaster. The takes were just so long, sometimes as much as 20 minutes, that you couldn't justify rerecording for the odd fumbled word. Brambell fluffed dialogue quite often and I would scream, "He's ruined it!" We were very precious in those days! In my mind any stumble on a line meant the joke was lost, and if it happened at all it was the old man doing it, but seeing the shows now you think, what was our problem? There's a little fluff, so what?' Alan Simpson remarks: 'He was playing an old man, so you can forgive it within the characterization, and apart from that Willie was always very professional. He was a good actor and could recover very well and very quickly.'

Old man Steptoe's hoarding instinct and his pathetic love of 'beautiful' things - actually worthless pieces of junk - soften the harshness of the character. The plate that he values so highly is painfully apt in its shabby appearance. The script does not specify that it should be particularly dilapidated, but the props department's offering allows Brambell to get excited over a cracked and broken 'find'. However, Corbett's flight of educated fancy as he appraises the item is at best short-sighted, and at worst completely inaccurate. As he chastises the old man's ignorance, Harold's own 'expertise', the very quality that he believes will free him from this shoddy business, is exposed as lacking. Although the old man is convinced by Harold's opinions and is hurt by the dismissal of his old, experienced 'eye' for a bargain, Corbett's performance suggests that he knows he himself is walking on very thin ice. Harold knows as little about antiques as his father does. The audience, picking up his faux pas, realizes it too. The cluttered grandeur of the Steptoe home adds further depth to the performances. As Corbett enters the living room, realizing from the haphazard display of 'precious things' that his father is up to something, he removes his cap and places it on the stuffed head of a leopard. It gets a laugh, but it isn't consciously a bit of funny business. For both Harold Steptoe and Harry H. Corbett, this is the most natural thing in the world: 'Although I've put a lot of myself into Harold Steptoe,' Corbett reflected, 'we had a lot in common right from the start.'

As the episode draws to a close, it is a testament to both the writers and actors that the viewer's sympathy shifts from one character to the other with almost every line of dialogue. We can, regardless of age or experience, empathize with both of them. Albert Steptoe's vindictive joy in refusing to allow his son the use of the 'family' horse reveals his essential selfishness, but the frailty and helplessness that Brambell brings to his performance suggests a frightened, lonely person who hides insecurity with a ruthless streak. Brambell embodies the vulnerability of impending age in his hunched posture, shuffling walk and wounded expression. The leers and grunts - which would become assured and often overused crowd-pleasers in the years to follow - are used sparingly here. The pathetic gesture with which he offers his son the plate is poignantly played. The son's dismissive rejection of this most prized possession symbolizes his rejection of his father, and Brambell's performance shows that the character realizes this only too well. And so our attachment shifts from the junior to the senior member of the household. The script gives no conclusive indication as to whose side the audience should be on, and that is the real beauty of the piece.

This was very much a new sort of comedy and, indeed, a new sort of television. Attention to the working classes was a rarity, but actually making them the heroes of a sitcom was ground-breaking in the extreme. The audience for this landmark production was still very much tuned in to a more unsubtle, lowbrow style of comedy. During this first half-hour of Steptoe perhaps the biggest laugh comes from the sight of a lavatory lugged off the cart by the disgruntled young man. By the end of the programme, great swathes of the emotionally charged dialogue are met with complete silence.

Brambell's desperate cunning and Corbett's determination to cut loose are interspersed with just the occasional comic line. Indeed, by the close only the odd member of the studio audience can produce a subdued chuckle at Brambell's tearful, affectionate reassurances. The near-tragedy of the last scene, as Brambell looks on helplessly while the son he loves seems to collapse with despair, is as powerful as Steptoe ever got. The audience is speechless. One can imagine why series potential was seen in The Offer: it is powerful, meaningful and, above all, real.

Alan Simpson was delighted not to get any laughs during the conclusion: We watched that closing scene as Harry literally crumbles. He's trying to push his meagre belongings away and start a new life, and he can't do it. We were watching this scene and Harry actually broke down and cried and I thought, real tears! This is what it's all about... this is acting! We weren't used to it with writing for comedians. Usually it would be stylized, shoulder-lurching sobs when comics cried. Harry really got hold of that final scene. It was real drama to him. The writers' avoidance of the easy-laugh conclusion marked the start of a new sensitivity. This wasn't just comedy any more; this was real life. In Steptoe and Son, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson have evolved character drama entirely new to television: deeper, truer, sadder, funnier than anything that has gone before. 'It's really tragicomedy, which is the essence of everyday life,' intoned Harry H. Corbett in 1965. As Ray Galton comments as regards comic portrayal of the working classes: 'I can't think of anybody else who was trying to make you laugh and cry at the same time like we were trying to do.'

Published on February 17th, 2019. Review: Robert Ross - taken from his book 'Steptoe and Son' published in 2002 by BBC Books. Reproduced with the author's permission..