Frankie Howerd

With his trademark "oohs" and "aahs", Frankie Howerd rose to the very pinnacle of comedic success in the United Kingdom and in spite of a few ups and downs managed to stay there for almost fifty years. After carving out a flourishing radio career for himself he went on to successfully master the medium of television and had some success on the big screen, too. Although his best-known catchphrase was, "Oh, well, please yourself" it was pleasing the audience that came so naturally to him, whether they be old or young or from whatever walk of life. In spite of long periods of self-doubt Frankie Howerd was one of the first comedians to cross the so-called generation gap and his humour knew no class barriers.

Francis Alick Howard was born on 6th March 1917 in a typical two-up, two-down terraced house, which spilled down to the River Ouse, in York. His father was a sergeant in the Royal Artillery and his mother worked in a chocolate factory, so although the Howard's were not "well off", they were certainly not as poor as Frankie would allude to in later years. By the time young Francis reached his third birthday the family had dug up their roots and moved to Eltham in South East London -which was the birthplace of Bob Hope.

At this time the area had not yet been gobbled up by London's expanding development and as such it managed to retain its rural status. It was here that Francis grew up with his sister, Bettina, and his brother, Sidney, although he remained something of a shy loner who did not make friends easily and was happiest walking alone among the nearby Kentish fields. He first got the show-biz bug when his mother took him to a pantomime at the Woolwich Artillery Theatre (his father was stationed at Woolwich). The visit had a profound effect on him and he would later recall that he never lost his sense of wonder for pantomime from that day onwards. "It transported me to another world." He said. "That's all you can ask of any theatre."

The show left a big enough impression to provoke young Francis into writing simple stage plays and floor shows that he would perform at home among cardboard sets that he also created himself. However, his siblings were not particularly enamoured by his efforts and they seemed to leave little lasting impression on them. However, Francis was not discouraged and over the years, with the help of a small troupe of local kids, he would develop small concerts that would be performed in the family's back garden. But it was at Sunday School that Francis literally stumbled upon the formula he would develop as his professional persona.

He soon realised that with a little preparation he could prepare a story for the Sunday monologue that would hold the attention of his listeners. However, even with this preparation, he was still unable to overcome an annoying nervous stammer that would accompany his dialogue. It didn't matter, for it soon dawned on him that this stammer could be used for dramatic effect, and from these realisations the basis of an act was formed. Francis joined a number of dramatic societies and by the age of 16 was confident enough to apply for a place at RADA. He was turned down.

"Never before or since have I wept as I did on that day," was how he described his reaction at being refused a place at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. But it was a career making turning point, because from that rebuttal Francis determined that if his future were not to lie in the direction of the serious theatre, then he would make it through comedy.

On leaving school in 1935 Francis took a job in an office in London's thriving dockland area. He joined the amateur dramatic circuit where he would perform by night for no money, with the sole purpose of refining his act. Although the venues could hardly be described as 'theatre', the acts he performed in places such as old people's homes, featured a small cast and were centred round Francis with such titles as The Frankie Howard Comedy Revue or The Frankie Howard Knockout Concert Party. He worked with an almost obsessive fervour, performing at variety halls, night clubs, anywhere there was a talent night or a stage to perform on, gradually honing his act to the point where he decided it was time to break into the more fruitful arena of professional show-business.

The Second World War changed people's lives irrevocably. Many career plans were put on hold, some were abandoned entirely, some were made, and millions were lost, having never been shared, -forever. The fortunate ones were able to incorporate their dreams whilst helping to defend their country. Francis Alick Howard was one of the fortunate ones. Stationed at Shoeburyness Barracks on the Essex coastline, Gunner Howard found an audience that was ready to be entertained and he was more than happy to oblige. Now billed as Frankie Howerd, he had refined his act with its trademark "oohs," and "ahs", his deliberate dithering and forgetfulness played for all its worth with expert comedic timing, by now he had also injected a biting sarcasm in his jokes and when he deemed it funny he directed that sarcasm towards his audience. He soon found himself as head of a concert party and with dogged determination he once again used this group of would-be entertainers (they were called The Co-Odments) to selfishly showcase his own talent.

Frankie tried unsuccessfully to join Stars in Battledress, which would have enabled him to entertain the troupes on a much larger scale, and instead he had to content himself with makeshift stages at Chelmsford, Basildon and Southend, and later still in Plymouth. He undertook Commando training at Devon and soon found himself following the invading troupes as they marched inexorably through France, Belgium, Holland and finally, as the war ended, Germany. Here he had another stroke of luck coming under the command of Major Richard Stone, who in civvy life had been a hugely respected theatrical agent.

After being demobbed Frankie returned to London where he knocked on the door of every agent he could find, but with only amateur experience as an entertainer he was unable to impress any of them sufficiently to take him on. Demoralised and desperate, Frankie took the illegal step of donning his army uniform and, clutching a reference that he had from Richard Stone, turned up at the Stage Door Canteen, which was run by the Naafi (Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes) that provided British Military personnel as support acts to passing showbiz stars. Although it was unpaid it was a chance to invite agents to see him perform on a West End stage. His bluff worked and not only did he secure a spot but he was asked to return for a second week. It was during this second week that Frankie was spotted by an agency rep and from this he was offered a contract. After years of being rejected Frankie Howerd was about to turn professional.

Frankie arrived in Sheffield in the summer of 1946 in a touring revue called Just For the Fun of It. Here his name appeared at the bottom of the bill along with another aspiring entertainer, Max Bygraves. By all accounts they stole the show. There followed the opportunity to take his act to the BBC for the popular radio show Variety Bandbox and by refining his act even further he gradually perfected a successful radio delivery that made him a smash hit with his listeners. Like every successful comedian of the time, Frankie coined a few easy-to-remember catchphrases and terms such as "Not on your Nellie" and "Oh, please yourself" soon began to filter into everyday life. His regular radio spot also attracted a number of wannabe scriptwriters, also eager to break into the world of show business. One of these was Eric Sykes, who allegedly walked into Frankie's dressing room in Sheffield one night and claimed that he'd soon be writing scripts for him. It proved to be no idle boast and a partnership was formed that laid the foundations for a hugely successful career for both men. In the defining moments of the history of British comedy, the coming together of these two talents has often been disregarded as insignificant. It was probably one of the most significant of its age.

Max Bygraves stated that even before Frankie Howerd became famous he broke every rule that he (Bygraves) had learned about entertaining an audience. This dishevelled looking man would walk on the stage as if he'd just clambered over the stools and proceed to deliver his act in a conversational manner, often stammering and often forgetting his lines or the denouement of a joke. Although this may not seem particularly radical by today's standards one must remember that in the late 1940's and early 1950's audiences had been bought up with fast-talking highly polished acts of flashy comedians who would waddle onto the stage with "I say, I say, I say...here's a funny story", or be dressed in garish colours with wide kipper ties and go into a song and dance routine. This was the role of the funny-man, the all-round entertainer.

With the introduction of Eric Sykes, Frankie's act became even more revolutionary, as the writer placed him in a number of surreal situations, all of which Howerd would deliver in his own inimitable way. It was, unquestionably, the dawning of a brand new age of comedy. Irreverent, innovative and at times controversial, Frankie Howerd was a rising star who proved that conventions were there to be broken and this inspired a new age of comedy and comedians in the UK. Then, at the very point of his career that Frankie Howerd was reaching his peak, his world fell apart.

A disastrous appearance on the Royal Variety Performance, where his nerves got the better of him, was followed by a forgettable radio series called Fine Goings On. On this occasion Eric Sykes writing failed to hit the mark with the show's star who was supported by a young Hattie Jacques. Frankie became depressed to the point where he thought his showbiz career was over. But from that depression he resolved to confront his fears and came up with the idea of returning to perform for the British Troops. The plan was to take Eric Sykes and a small team of BBC recording engineers on a tour of Tripoli, Cyprus, Egypt and Benghazi and write entire concert parties on the move. Cast members were randomly plucked from RAF personnel and placed in front of microphones with hastily written scripts. The show, titled Frankie Howerd Goes East, was an anarchic mess that was hated by the BBC and savaged by the critics. It was a show that was years ahead of its time, in complete contrast to anything the BBC had ever transmitted before, and totally out of character for the Corporation. And the listeners loved it!

Filled with a new confidence, Frankie returned home triumphantly and was offered a new show on a new medium. Television. On 11th January 1952 he starred in The Howerd Crowd with the Beverley Sisters. The BBC at this time had still not come to terms with and was still trying to find a successful TV comedy format. Although the format was much more controlled than his recent radio outing, Frankie still insisted on trying out new ideas, including the provision of his own cameraman who was instructed to keep track of Frankie throughout the show. "I looked like a pasty faced village idiot who needed a set of false teeth", Frankie noted of that first TV performance. But village idiot or not Frankie became a familiar face on television throughout the 1950's with numerous specials written by Sykes, Spike Milligan and Johnny Speight. A Galton and Simpson-penned radio series kept his listening fans happy (not everyone owned a television in the late or mid-fifties) and there was also the promise of a film career. His big-screen debut came in The Runaway Bus in which he co-starred with Margaret Rutherford and a young Petula Clark. The movie hardly set the film world alight, but it was an undemanding little comedy that had its moments, in particular a scene in which Frankie goes into a telephone box and ad-libs a conversation. The scene was allegedly added after filming was complete when it was discovered that the running time was three minutes short of getting the film a West End screening.

In spite of a run of film roles as the 1950's drew to a close so did a chapter in Frankie Howerd's life. His humour, which had seemed so anarchic at the start of the decade, was now looking a little dated. It was not Frankie's fault. Eric Sykes was now a star in his own right, appearing in front of the cameras instead of behind a script. Spike Milligan had taken comedy to new levels of anarchism with his hugely successful Goon Show scripts, and with the emergence of Rock n' Roll television demanded a younger more vibrant performer. By the start of 1960 Frankie Howerd discovered that he was no longer in demand. He began to lose confidence in his own performances and word soon got round the London booking agents that Frankie Howerd had lost his audience appeal. Bookings dried up and by 1962 Frankie decided he'd had enough of Showbiz and began looking around the southeast for a pub as he considered a career as a landlord.

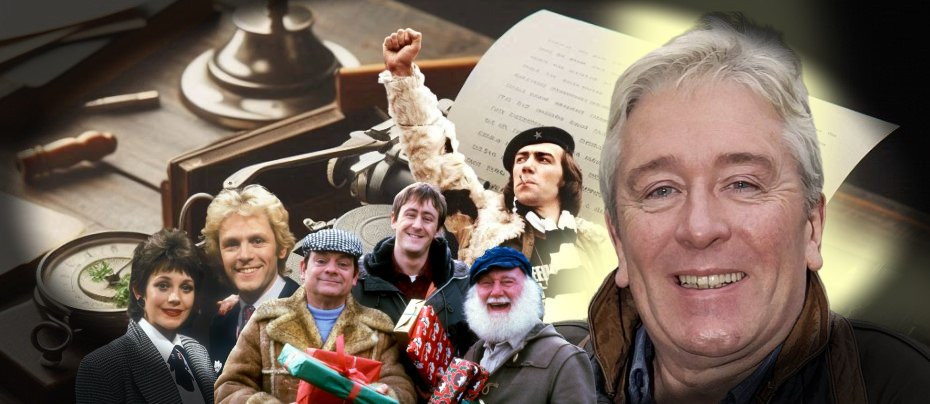

At the precise moment that Frankie had deigned to give up his professional career his mother, who always believed her son would be a great star, died. The very next day he received an invitation to appear on Alma Cogan's Star Time show on ITV. The offer took him completely by surprise. "I really had totally given up at that point," he said years later. "I had reached the point of no return and then, with my mother dying, something snapped. I'd just gone. And just at that point something reached out and pulled me straight back in." More television followed with an appearance on the Billy Cotton Band Show, and this was immediately followed by a new radio series written by Barry Took and Marty Feldman. The turning point, though, was an invitation by Peter Cook for Frankie to appear at the recently opened Establishment Club, which had followed in the wake of Cook, Dudley Moore and Jonathan Miller's legendary Beyond the Fringe success. Frankie appeared there performing a script written by Johnny Speight. "It was very odd," recalled Speight "because Britain had just latched on to satire and producers were screaming for "the new comedy", as they called it. All the agents and producers regarded Frankie as "old school" but none of the new generation of comedians or writers saw him that way. In fact, we saw him as the perfect vehicle. He could read anything and make it funny."

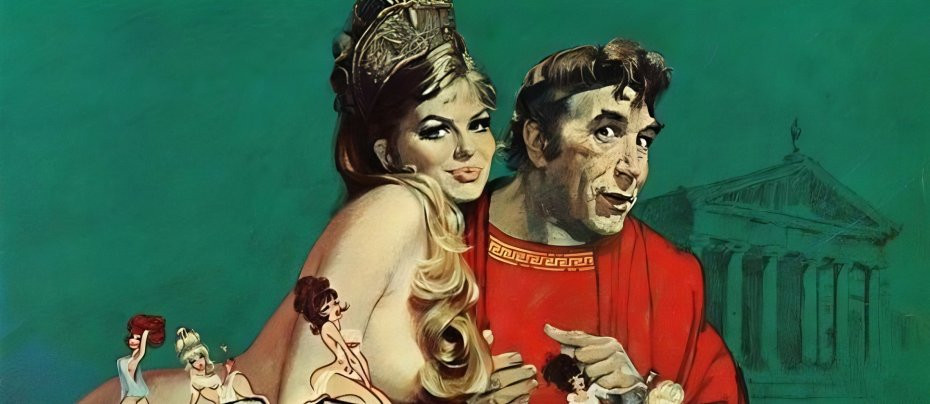

With his success at the Establishment Ned Sherrin booked Frankie for guest spots on his groundbreaking satirical TV show, That Was The Week That Was. The constant exposure on radio and television totally revived Frankie's career and it wouldn't be long before he made a triumphant return to the London stage. A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum had been a smash hit on Broadway. The tale, written by Stephen Sondheim (based on the book by Larry Gelbart and Bert Shevelore) was a bawdy romp that seemed to owe more to British saucy-postcard humour than it did to vaudeville. Nevertheless, it had taken Broadway by storm by virtue of the fact that it was so completely different to anything else that was playing at the time. When it was announced that the show was coming to London it's producers, Hal Prince and Richard Pilbrow, turned to no less than leading thespian John Gielgud for casting advice. "The show was pure Frankie without Frankie knowing about it," he said. "And when Hal Prince and Richard Pilbrow asked me if I knew who could play the London lead, well there was only one name on my mind." Taking Gielgud's advice Frankie was offered the part of the Roman slave Pseudolos, who in the plot is trying to win his freedom.

The show opened in London on 3rd October 1963 to good solid reviews, but fell short of setting the theatre world alight. Frankie later admitted to suffering from terrible first night nerves but as he settled into the role so critical opinion became more favourable. In any event, the show ran for almost two years until June 1965. During this period Frankie should have cemented his comeback with a cameo appearance that would have been seen the world over. The Beatles, who at that time were probably the biggest show business phenomenon ever seen, invited Frankie to appear in their second feature film Help! Frankie duly agreed and arrived for filming on the first day to find the studio besieged by teenage girls, hoping to catch sight of their idols. "They would hurl themselves at anyone who looked as though they might be vaguely connected with the Beatles," he later recalled. "It was certainly bewildering to me." Not as bewildering, though, as the fact that the sequences in which Frankie appeared never made it onto the screen, having been left, it seems, on the cutting room floor.

In the winter of 1966 Frankie returned to BBC TV once again in six half-hour shows written by Galton and Simpson then later still Eric Sykes approached him with an offer to star in Way Out in Piccadilly, a show that would feature the West End debut of Cilla Black. The odd combination of the experienced old trouper and the teenage pop idol worked perfectly from the word go, mainly due to the fact that the two stars formed an instant rapport and a long standing friendship was formed during the twelve month run that the show enjoyed. 1966 was rounded off with a successful appearance on the Royal Variety Show and the coveted award of 'Showbusiness Personality of the Year.'

In 1968 Frankie made his first appearance in a Carry On film with "...Doctor", in which he played Francis Bigger, a faith healer who ends up in hospital. But it was 1970's "...Up the Jungle" that can be seen as the next significant step in his career. The film's scriptwriter, Talbot Rothwell, had been working on a half hour sitcom version of A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum. The story goes that Michael Mills, who was the head of BBC comedy, was on holiday in Italy when he visited the ruins of Pompeii. On seeing the remains of the bordellos and shops he turned to a friend and remarked (in an obvious reference to "Forum") how he expected to see Frankie Howerd "come loping round the corner." On returning home he contacted Rothwell and suggested the sitcom idea with Frankie as its star. Rothwell was so taken by the idea that he dropped several other planned projects to work out a format and several scripts. By the time shooting started on "Jungle", Rothwell was in a position to approach Frankie himself. He loved the idea but had some reservations.

Oddly, for someone who had a reputation for bawdy humour, Frankie was a little concerned about the risquè jokes and half naked women that would feature in the series and insisted that a pilot of Up Pompeii be made to test the reaction of the British public. He needn't have worried. The public and critics alike loved it, the only dissenting voice coming from 'Clean-Up TV' campaigner Mary Whitehouse, a fact that almost certainly cemented its success. Over the next two years Frankie made fourteen episodes of the series and it is the one, even today, that he is most closely associated with in the mind of the television viewing public, not just in Great Britain but as far afield as New Zealand, Australia and Canada. There were also three feature films but only the first of these really captured the essence of the TV series. In 1972 the BBC requested a third series of Up Pompeii but a combination of Frankie's reluctance to do a third series, and Talbot Rothwell's poor state of health precluded the project getting off the ground. The BBC tried to revive the format in a similar series titled Whoops Baghdad, but the lack of a Rothwell script and Frankie's obvious lack of confidence in the character was clearly visible to the viewing audience, and the series quickly faded from memory.

It is a fairly reasonable argument that the success of Pompeii weighed heavily on Frankie's shoulders for much of the following decade. In 1982 Frankie was offered a new sitcom by the BBC. Then Churchill Said To Me was a wartime romp that still owed much to the characters that Frankie had played in previous TV series'. However, the series was held back by the BBC when a real war broke out in the Falklands. Deemed unsuitable for viewing at that time "Then Churchill Said To Me" lay on the shelf gathering dust for 11 years before finally getting an airing on the cable/satellite channel UK Gold. If one looks at his achievements in the 1980's it is quite clear that his television appearances became fewer and far between. Where Frankie had revelled in the political satire of 1960's TW3, by the 1980's he was better remembered for the bawdy humour of his Roman slave character, Lurcio. And in the politically correct eighties there was no place for such a format. But Frankie had proved himself the master of the comeback and he took his one-man show, Frankie Howerd Bursts into Britain, on the road and began to attract the attention of the countries new wave of 'alternative' comedians, of whom it could be argued Frankie was the father, or perhaps more accurately the grandfather, as he was now over 70 years of age.

He also gained a reputation of being something of a cult figure among Britain's university campuses as clearly illustrated in the televised Frankie Howerd on Campus, which was filmed at Oxford University in 1990 by London Weekend Television. That same year the BBC presented an edition of Arena - the popular arts programme, called Oooh Er, Missus! -The Frankie Howerd Story, in which the comedian looked back on his own career. Frankie Howerd had, it seems, made yet another successful comeback.

Despite ill health, Frankie continued to build on his reputation among Britain's campus fraternity until he died of a heart attack on 19th April 1992 at the age of 75. He was a unique talent whose humour transcended and entertained generations of fans. With his unique ability to constantly reinvent himself Frankie Howerd seemed almost timeless in his appeal. He was one of Britain's -nay and thrice nay, one of the world's, all-time greats.

Published on February 20th, 2019. Written by Laurence Marcus (2002) for Television Heaven.