The Shakespeare Collection

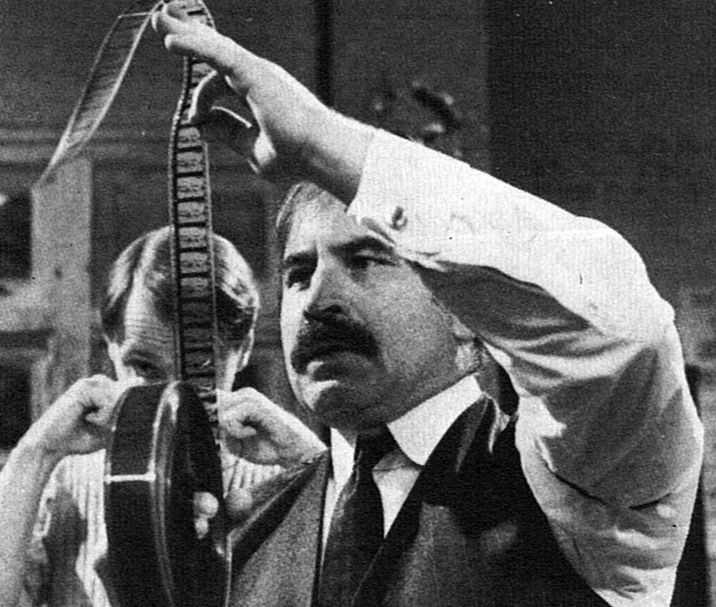

In 1978, Cedric Messina persuaded the British Broadcasting Corporation to take on the task of filming the whole canon of William Shakespeare's plays for television, under the title The Complete Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare.

Throughout the project, which was finished in 1985, the BBC was able to secure leading actors of stage and screen and also big directing names. The BBC Shakespeare DVD box-set, comprising 37 discs, is a unique collection of some of the finest dramas in the English language, each production a celebration of the greatest talents in contemporary British theatre and television. These plays feature the cream of the 20th century's acting talent. It is reviewed here by John Winterson Richards.

The first thing that must be stressed is that, while there are many five-star moments in this great undertaking, it would not be right to give five stars to the whole because there such is an enormous variation in the quality of these 37 productions. This is in large part because there is an enormous variation in the quality of the 37 plays themselves. Whisper it, but many of them would be all but forgotten today, and in some cases rightly, if they did not happen to be written by the man who also wrote Hamlet, etc. On top of that, there is a wide variation in the production values of this collection.

This started out as a major prestige project by the BBC, complete with a wonderfully pompous score by Sir William Walton, expensive outside broadcast location work, and big name Shakespearean actors: the opening words of the whole project are spoken by Sir John Gielgud himself in Romeo and Juliet. However, by the end, the budgets had obviously become a lot tighter, the sets more stage-like or even studio-like, and the casts dominated by television regulars, albeit generally good ones.

There is a feeling of "let's get this thing done" about a few of the later productions. In between came Dr Jonathan Miller's attempt to impose a Baroque house style on the project.

At their best, his sumptuous visuals are an artistic treat in their own right, as well as serving to lift some of the weaker plays, like Cymbeline, but it cannot be denied that they can be an irritating distraction in those productions, notably King Lear with Sir Michael Hordern, which have the dramatic power to involve the viewer without the need for gimmicks. Indeed, taking the project as a whole, it is fair to say its greatest successes were some great productions of some of Shakespeare's lesser works, but its productions of the more famous plays fell short of the very greatest adaptations of them.

That is only be expected, and is in itself no criticism, because the competition is so overwhelming: for example, there is nothing wrong with this BBC version of Henry V but with the Olivier and Branagh versions easily available why bother watching one with television production values? Yet those same television values have been turned to advantage in plays where the viewer might have lower expectations. The difficult Henry VI trilogy turned out to be one of the triumphs of the project, thanks to the inventive use of a single stage-like set and the employment of a strong team of actors in multiple roles - a concept Shakespeare would have recognised and enjoyed. A different approach, exploiting television's ability to use outside broadcast locations, lifted Henry VIII above its usual level as a Tudor propaganda piece - again, aided by a superb cast.

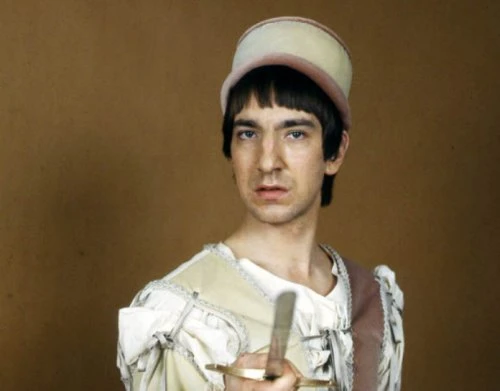

Good casting is the underlying strength of the whole project. It coincided with both the Golden Age of British television and the end of the post-War Shakespearean revolution on the stage, and it used actors from both. It is also interesting to see young talents who have since made it on the big screen showing early promise. If there are a few obvious mistakes in the casting, they stand out only because the general quality is so good.

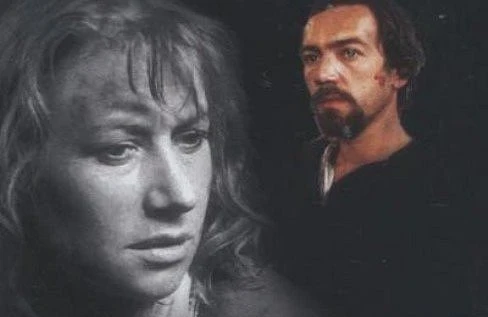

The project is distinguished by having more than its fair share of bench-mark performances, which set, or should set, the standard by which subsequent performances may be judged, including, among others, Hordern's Lear, the future Dame Helen Mirren's Rosalind in As You Like It, Sir Anthony Quayle's Falstaff in Henry IV, the future Sir Derek Jacobi's Richard II, the future Sir Ben Kingsley's Ford in Merry Wives of Windsor, Keith Michell's Antony in Julius Caesar, Trevor Peacock's Talbot and Bernard Hill's York in Henry VI, Timothy West's Wolsey in Henry VIII, Joss Ackland's Menenius in Coriolanus, Norman Rodway's Apemantus in Timon of Athens , John Shrapnel's Hector and Charles Gray's Pandarus in Troilus and Cressida , Felicity Kendal`s Viola in Twelfth Night, Claire Bloom's Gertrude in Hamlet, Hugh Quarshie's Aaron and Edward Hardwicke's Marcus in Titus Andronicus, Bob Hoskins' Iago in Othello, Peter Jeffrey's Parolles in All's Well That Ends Well, Jeremy Kemp's Leontes and Margaret Tyzack's Paulina in The Winter's Tale, Jane Lapotaire's Cleopatra in Antony and Cleopatra, Tony Doyle's Macduff in Macbeth, Cherie Lunghi`s Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing ...the list could go on. All stick in the memory.

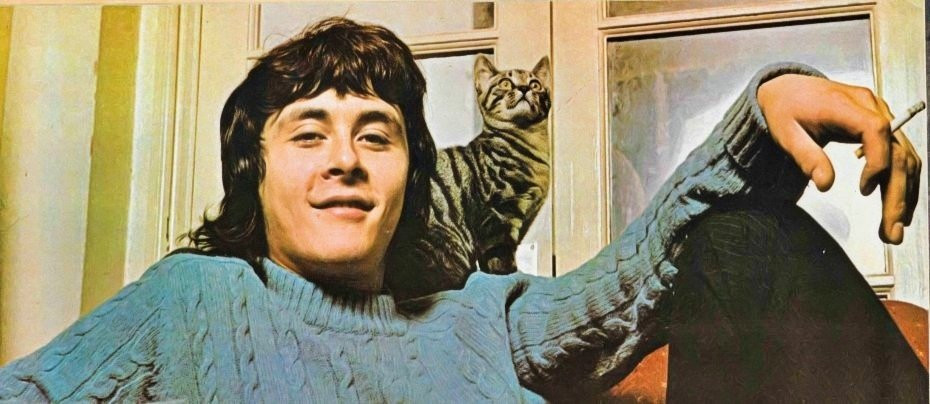

The casting of John Cleese as Petruchio in the Taming of the Shrew and Leonard Rossiter as King John, both considered daring in their day, stand the test of time very well. It is also good to be reminded that Sir Donald Sinden, Clive Swift, and Robert Lindsay, actors now best known for their sitcom work, are first class Shakespeareans.

A number of actors, including Hordern, Mirren, and Lindsay, appear in several different plays, so that the project sometimes has a pleasant "repertory" feel to it: it is a shame that this aspect was not developed further. Watching the whole thing over the last couple of months has given the best possible overview of Shakespeare - and it would have been life-changing to have had the opportunity to do so as a teenager, when they first came out but over a period of seven years.

As it is, this beautifully boxed set would be the perfect gift for any young person with intellectual, literary, or dramatic inclinations. It is an education in itself and a significant contribution to recent British cultural history.

Published on September 25th, 2019. John Winterson Richards.