Doctor Who: The Daleks

"The Daleks were, in their original conception, quite different from the galactic conquerors they are now"

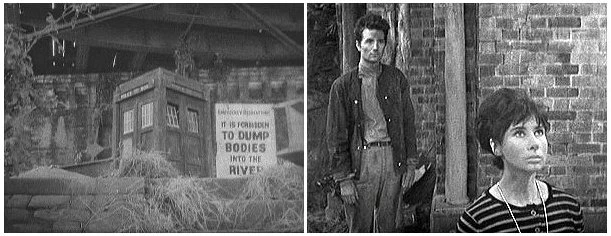

The Daleks made their first appearance on the 21st of December 1963, courtesy of a sucker arm pointed aggressively at Jacqueline Hill during the cliffhanger ending to the episode "The Dead Planet." It wasn't until a week later that viewers got their first look at the conical alien machine-beings, and 1964 was greeted by children running down the streets of Great Britain screeching "I am a Dalek!" in staccato voices. The monsters were a gigantic hit, and launched the fledgling Doctor Who on the way to become a global phenomenon.

However, the Daleks were, in their original conception, quite different from the galactic conquerors they are now. Indeed, the Doctor himself was a far cry from the heroic figure he is now perceived as. Watching that first Dalek serial, and its follow-up, The Dalek Invasion of Earth, illustrates the rapid evolution of both the Daleks and their nemesis, the Doctor, as they were reconceptualised as something quite different from their initial story functions. In the 2014 episode Into the Dalek, Peter Capaldi's Doctor declares that the Daleks made him the man he is today, existing to oppose them and everything they stand for. Back in '63, there really wasn't that much difference between them.

The first Dalek serial was broadcast in seven episodes over the '63-4 holiday period and into February. During the first three seasons, Doctor Who episodes had individual titles, strung together into serials which lacked any onscreen appellation. While most stories have commonly agreed titles from a variety of sources, the earliest few are known by many, none more so than Serial B. While generally referred to as The Daleks, not least by today's BBC marketing materials, other names are often used, including "The Mutants," "Beyond the Sun," "The Dead Planet" and "The Survivors." For simplicity's sake, when a title is necessary we'll use The Daleks, as that is currently the most official. The story was written by Terry Nation, a jobbing scriptwriter with a canny agent. His scripting was full of ideas and boys' own thrills, but was short on description. His concept, of a world devastated by a nuclear war between two races, was padded out with plenty of captures, daring escapes and dangerous escapades, a style that would become a staple of his scripts for Doctor Who, and to a fair extent, the series as a whole.

The planet is called Skaro, and a handful of survivors of these two races still exist, five centuries after the devastating neutron bomb ended the war, along with almost all life on the world. According to the history expounded in the story, the Dals were once scientists and philosophers, but nonetheless warred ferociously with the Thals, a self-proclaimed race of warriors. The survivors of the two peoples suffered from horrendous mutation due to the radiation levels left by the war, radiation that is just starting to subside as the serial begins. While the Thals' mutation had come "full circle," leaving them as beautiful humanoids, the Dals had become the Daleks, horribly deformed creatures who existed more as brain than anything else, kept alive in travel machines, reliant on radiation and confined to a metal city. Neither side is even sure the other still survives.

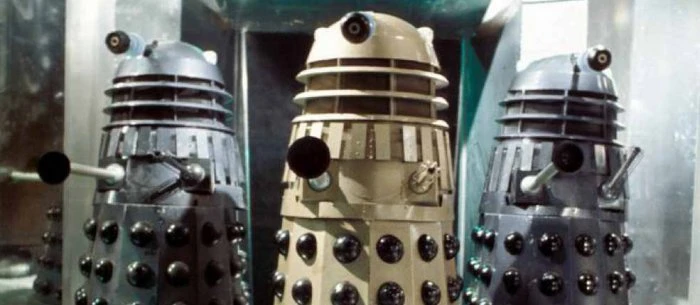

Nation's description of the Daleks, the series main feature, was vague indeed. One Ridley Scott was assigned to design the story, but was poached by Granada and began directing (the rest, as they say, is history). It was up to his replacement, Raymond Cusick, to create the Daleks and their city, although he did have some preliminary discussions with his successor. One thing Cusick, Nation and producer Verity Lambert all agreed upon was the desire to make the creatures seem alien, and not obviously a man in a suit. (Scott would face a similar challenge fifteen years later, when he created Alien.) Chatting with Nation, Cusick took the Georgian State Dancers, who would glide around with their sweeping skirts, as inspiration. From this, and the simplistic script directions, Cusick designed a mechanical creature that hid a seat on wheels within a broad, skirt-like base. By allowing the performers to sit, not only could the Dalek props be operated for longer periods, the unwanted human form was broken up. Atop this base was a midriff with two mechanical arms, and dome, displaying a single telescopic eye. One arm would be used as a weapon, the other as a manipulatory appendage. With little money or time, Cusick and the construction group ended up using a whisk-like design for the gun, and what was very clearly a sink plunger for the second arm.

The design might seem ridiculous now, but it was visually striking, unnervingly alien, and above all, perfectly suited to the world that Cusick created in tandem with his creatures. Shawcraft Models were engaged to create the Dalek city according to Cusick's conception. Nation's script described the Daleks as running on static electricity drawn up through metal floors, along which they would glide like dodgem cars. Nation's script, Cusick's city and the Daleks fit perfectly. The Daleks have no legs because they never leave their habitat, where the floors are polished smooth and all levels are connected by elevators. Their peculiar appendages fit with the controls to their systems. Even their camera eyes are reflected in their surveillance systems. The only elements that don't add up are the suspiciously human-friendly prison cells and stationary.

The final piece of the puzzle was the Daleks' voices. Conceived as being as mechanical as their appearance, the Dalek voices were created by Brian Hodgson, part of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, who modified old post office equipment into a device he called the ring modulator. This broke the human voice into pulses as it was spoken through the microphone. The actors who supplied the creatures' staccato delivery were David Graham and Peter Hawkins. The former had worked on Thunderbirds and other Gerry Anderson productions, and would later make some onscreen appearances in Doctor Who. Hawkins was ubiquitous in sixties children's TV, having provided the voices for such characters as Captain Pugwash and Bill and Ben, the Flowerpot Men; he would become particularly identified with the Daleks over the following years.

Although their machine-based appearance might suggest otherwise, it was explicit from the outset that the Daleks were not robots. These were organic beings, horribly altered by radiation, as evidenced by the nauseous looks on the heroes' faces when they are forced to open one up during their escape from the Dalek cell. The third episode (extravagantly titled "The Escape") ends not on a cliffhanger, but a reveal. The Dalek is practically scooped out from its carrier in a cloak, and dumped on the floor to die. All we see of it is a feeble claw, reaching helplessly out from beneath a cloak too heavy for it to lift. Even though the "claw" is nothing more than the arm of a gorilla costume, covered in Vaseline, it's hugely disquieting. Somehow, even in monochrome, it's obviously green.

The menacing creatures were an instant hit with Britain's children; scary enough to make the episodes exciting, not so scary they couldn't stand to watch, unique in appearance and, importantly, easy to imitate. The gentleman in overall charge of the series, Sydney Newman, hated them. He had a strict rule about the series: "No bug-eyed monsters." Thankfully, producer Lambert was able to talk him round, and he allowed the episode to go into production, Daleks intact. Newman was magnanimous enough to admit that, in this instance, his judgment had been wrong.

The antecedents to Nation's story are such adventures as H.G. Wells's The Time Machine, and the adventures of Dan Dare in the fifties children's magazine The Eagle. Both featured two races sharing a world, one brutal and monstrous, the other serene and handsome. The Time Machine had the split descendants of humanity, the underground Morlocks who fed upon the beautiful but helpless Eloi. Dan Dare's adventures are an even more obvious precursor, with Venus inhabited by statuesque, blond-haired Therons and warlike, green-skinned Treens. (The similarity between the Treens' stunted leader, the Mekon, and Nation's later creation, Dalek-creator Davros, make the parallel even more obvious.) This, and the 1960 film adaptation of The Time Machine, would have been familiar to Nation, and the similarity between the Thals, Therons and the cinematic Eloi is striking. All are blond, athletic and beautiful. While the militaristic, purity-obsessed Dalek invaders of later serials are frequently likened to the Nazis, it is the Thals who are distinct manifestations of the Aryan ideal.

"The phenomenal popularity of the Daleks made their return inevitable"

One thing the Daleks are not in this story is mighty intergalactic warlords. They were simply never designed to be, nor were they designed to return. Their violence against the Doctor's party and the now pacifistic Thals stems not from a desire to conquer, but from fear and desperation. Reliant on technology, trapped inside their own metal world, sent mad by their isolation in their travel machines, the Daleks are frightening but rather pathetic creatures. Their final plan involves once again setting off a neutron bomb, wiping out what little life remains on Skaro and flooding it with more of the radiation necessary to their survival, so that one day they might escape their city. Nation's story ends with them completely wiped out, victims of the "extermination" they had planned for the Thals.

However, the phenomenal popularity of the Daleks made their return inevitable. Nation, through some clever moves on his and his agent's parts, had retained a half share of the rights to the Daleks. Meanwhile, Cusick, a BBC employee, whose design of the Daleks had contributed to their success more than anything, received nothing except a small bonus. Viewer response and expectations had already built the Daleks up into something more than they were intended to be, and any sequel would have to be bigger and bolder than the original. The solution was fairly obvious, as much a science fiction staple as the set-up of The Daleks. The Daleks would be repurposed as alien invaders and brought to Earth, to battle the Doctor and his companions not for their world but for ours.

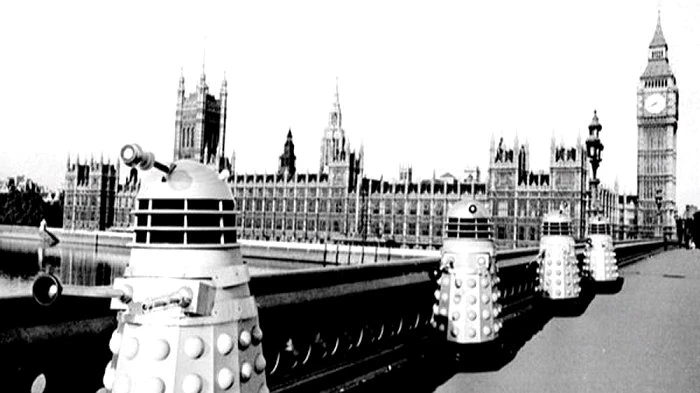

Logically, any expedition outside of their city, let alone off their planet, would have seen the Daleks redesign their travelling machines. This, however, was not an option for the production team, for the appearance of the Daleks was, and remains, their main selling point. Some tweaks were made; a wider base allowed more versatile wheels for outside filming, including several shots of Daleks patrolling iconic London landmarks. The invading Daleks also displayed large receiver dishes on their backs, ostensibly allowing them to accept power beamed to them wirelessly, explaining why they were no longer confined to electrified floors. Other than this though, the new Daleks were essentially the same as the originals in their appearance. Their other main point of popularity, their screeching voices, was kept much the same, although sounded rather less impressive in their second appearance; it would be some time before the voices were reverted to their original power.

The Dalek Invasion of Earth has a wholly different setting to The Daleks. While the original took place on an alien world, the sequel is set in a very recognisable London, albeit that is two centuries in the future of the audience. The Daleks have held the Earth in their grasp for ten years, as part of a frankly baffling plan which involves digging a shaft in Bedfordshire through the use of slave labour, in order to remove the Earth's magnetic core, install an engine and then drive the planet around the cosmos. Though the invading Daleks are certainly braver and more deadly than their cousins on Skaro, they don't seem to have much of a grasp of science. The intricacies of their mad plan are essentially irrelevant, however. The important point is that they have been wholly reconceptualised, no longer a race of needy survivors but as a group of tyrannical monsters. As mentioned above, the Daleks have been regularly likened to the Nazis, and this begins with this serial. It's worth remembering that when The Dalek Invasion of Earth was made, it was less than twenty years since the end of the Second World War. The adult audience had lived through a time when the invasion and occupation of Great Britain by an enemy force was a very real possibility. The point is driven home by the Daleks' salute - one arm held high - their propaganda broadcasts intended to quell the morale of the resistance, their slave labour camps, and more. They even refer to the extermination of the human race as "the final solution." It could hardly be more transparent, but it's most certainly effective.

As the Daleks changed, so did the Doctor, and the programme around him. In The Daleks, the Doctor's character still matches his original conception quite closely. He is mysterious, acerbic, dishonest and untrustworthy. While his character is already mellowing since his début a few weeks earlier, he's still not what anyone would call pleasant company. Having explored the petrified forest in which the TARDIS lands, he is desperate to explore the silver city in the distance. He is eventually persuaded to return to the Ship by his companions, Ian Chesterton and Barbara Wright, in spite of caring little for their wishes or safety. All he really seems to care about is his own curiosity and the safety of his granddaughter, Susan. In the TARDIS, he contrives a fault with the Ship's drives: a fluid link that requires refilling with mercury. His plan forces the party to go into the city, where they are captured by the Daleks.

In his earliest episodes, the Doctor, as played by William Hartnell, was a far cry from the hero of later years. The hero of the show was Ian, played by William Russell, the dashing leading man of the swashbuckling series The Adventures of Sir Lancelot. Ian, though curious of his new surroundings, was more concerned with getting himself and his friend Barbara (Jacqueline Hill), off this planet. Even Susan (Carole Ann Ford), wanted to leave this desolate planet. Once captured, the Doctor, addled by the radiation still in the atmosphere, contritely reveals his duplicity. The party escape, of course, but not without cost. Their presence has allowed the Daleks to lure the Thals into the city, resulting in the death of their leader. What's more, the fluid link is lost, still in the Daleks' possession; they'll have to go back to the city after all. This leads to the central moral debate of the story. The Doctor knows that they'll have no chance of retrieving the component without the help of the Thals. The Doctor is content to use them as a ready-made army, while Ian is unwilling to allow others to die on his behalf. It is, in fact, Barbara who sides with the Doctor, while Susan is more concerned with what plans the Daleks have for her new Thal friends. In time, Ian is persuaded that, if the now resolutely pacifistic Thals don't fight the Daleks, they will be wiped out themselves, and he, as the central hero of the serial, has to persuade them in turn.

After considerable peril and various deaths, Ian and Barbara lead the Thals into the city through the backway, while the Doctor and Susan lead an assault from the front. Captured once again, the Doctor decries the Daleks' plans as "senseless, evil killing," but his first concern is still for the safety of himself and his granddaughter. He even seems ready to give the Daleks the secret of space-time travel in return for his freedom, although he may, of course, be bluffing. In the event, he seems to take some little glee in the Daleks' own destruction as their power supplies are destroyed.

Compare this with the situation in The Dalek Invasion of Earth. While the same four characters are involved, and the TARDIS is once again put out of action in order to motivate the plot, this time the Doctor, upon learning the Daleks' plans for Earth, declares "They must be stopped!" Once again, Ian is the central hero of the adventure, with the Doctor more of an elder advisor. Susan's experiences as a romantic subplot, with young resistance fighter David Campbell (Peter Fraser), set up her writing out of the series at the adventure's close. Barbara, meanwhile, has her own adventures on the way to the Dalek mine. It's not quite the all-defeating Doctor of renown, but he has been soundly redefined as someone who opposes evil forces in the universe, his general character softening around this. Perhaps that first encounter with the Daleks really did change him; his first encounter with an entirely antagonistic alien culture. In that first encounter, the Doctor at least respected the Daleks as scientists; by the time he stops their occupation, he is diametrically opposed to everything they stand for.

While the Doctor's development is gradual and believable, there is no sense of continuity between the two conceptions of the Daleks. The two stories had been conceived for entirely different reasons. The Daleks was a morality tale about the dangers of war, in a time of rising tensions between the nuclear powers, while The Dalek Invasion of Earth is a straightforward fight against evil drawing on the cultural shock of the previous great conflict. A vague attempt is made to rationalise the two different groups of Daleks, with the Doctor claiming that their first encounter took place "millions of years into the future." An absolutely ludicrous claim, contradicting the half-a-million years of Skaro history described in The Daleks and utterly incompatible with later Dalek stories. Still, trying to make sense of Dalek history is a fruitless task. They have been continually reconceptualised as the series evolved, and the Doctor along with them. The Dalek Invasion of Earth saw the departure of Susan; Ian and Barbara would leave in the next Dalek story, The Chase in mid-1965. That serial, again by Nation, elevated both the Doctor and the Daleks to greater heights than ever before, with the Daleks acquiring their own time machine, in order to pursue the Doctor, now declared to be their greatest enemy. While Ian was replaced by Peter Purves as Steven Taylor, the Doctor was nonetheless becoming a more central and heroic character. Doctor Who was now undoubtedly his show.

The Doctor and the Daleks enmity would continue to escalate, their popularity and cultural impact pushing them ever higher in their one-upmanship. The Daleks would threaten the entire universe in 1966 with The Daleks' Masterplan. The Doctor faces down the Dalek Emperor and sets them into civil war in 1967 in The Evil of the Daleks. After a period without the monsters, they returned to face Jon Pertwee in 1972's Day of the Daleks, the Doctor becoming ever more a figure of power, the only man to scare the Daleks as they threatened the Galaxy. Davros took over as the focus of this feud from 1975 with the Tom Baker serial Genesis of the Daleks, but on the series' return in 2005, the Daleks had been promoted to the only force to threaten the Doctor's people, the Time Lords, capable of threatening all creation, while the Doctor has become a "lonely god" and a mythic figure in his own universe.

The Doctor and the Dalek had humble origins, but immediately, they had propelled each other to cultural stardom. The Doctor is never without the Daleks for long; their battle will surely continue until their universe ends.

Published on February 24th, 2019. Written by Daniel Tessier (August 2015) for Television Heaven.