Hell Drivers

Hell, yes

By Andrew Cobby

Some films obey the rules of the road. They keep a respectful distance, overtake when safe to do so and continue on their way with a friendly wave.

Hell Drivers acts like a road hog. It roars up on you all the way from 1957, honking its horn and filling your rear view mirror. Then it overtakes on a blind bend and zooms off leaving nothing but unfriendly hand gestures behind. Mirror, signal, manoeuvre means nothing to the hell drivers.

Just when you think you’ve seen the last, you pull up outside your house to find it blocking your driveway and refusing to budge until it’s good and ready.

Directed by C Raker Endfield in 1957 and starring Stanley Baker, Hell drivers is a thrilling depiction of male competitiveness among a group of truck drivers at Hawletts Contractors.

The drivers at Hawletts own the roads, and other motorists had better clear a path for them or risk being crushed under their wheels.

These are not the romantic English lanes of Ivor Novello. No, these are the grey, grimy, gritty highways and bye-ways of Britain, filled with lorries speeding their way to the country’s postwar rebuild.

I might as well confess at the start that I don’t know the difference between a truck and a lorry, assuming there is one. I could google it but I get the feeling it would be one of those searches from which I emerge more confused than when I went in. I googled ‘promontory’ recently and I still have no idea what one of those is.

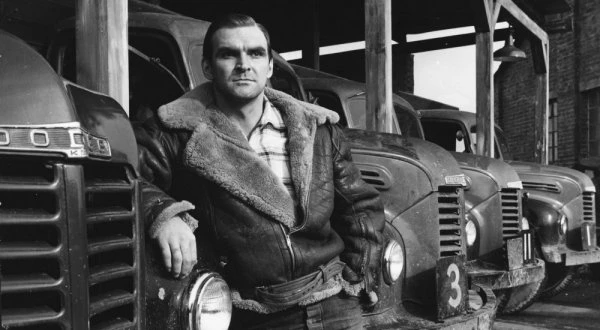

Mr Baker plays Joe Yateley, an ex-convict who fetches up at the contractor’s yard looking for a driving job. He is trying to go straight and, so desperate is he to break the links with his past, he even changes his first name to Tom. New name, new life.

The boss Mr Cartley is played by William Hartnell. He will shortly be keeping a seat warm for Sid James on the Carry On bus, but he makes do here with offering Tom a trial in one of his lorries. Wilfrid Lawton provides a memorably sly turn as the dour old mechanic Ed who rides shotgun during the journey. Tom’s trial run is quietly funny as he drives the lorry off the road only to have Ed’s backside waving defiantly in his face while Ed leans out of the passenger-side window to guide him back on to the carriageway.

Tom’s time in the cab with old Ed is right up there with Columbo taxiing a reluctant Larry Storch back to the DMV in that episode in which Dick Van Dyke plays the baddie. Both scenes are an unexpected source of fun that stay with me long after I’ve viewed them.

There is an age-old platitude that says that when life gives you lemons, make lemonade. As far as I am aware, there is no such guidance for those occasions when someone waves their behind in your face so I’ll apply my own guidance here - when you’re staring at the bottom the only way is up.

So it would seem to Tom. He gets the job at Hawletts and catches the eye of the office secretary Lucy, played by Peggy Cummins looking not a little like Kylie Minogue. 1957 was a golden year for Ms Cummins as that was the year she also appeared in the excellent Night of the Demon.

It is apt that Lucy resembles Kylie because she is an early exponent of girl power. Petite but more than able to keep a hut full of lorry drivers in their place, she is a self-sufficient lady, driving around in a jeep and revelling in her role as the keeper of all the company secrets.

Actually, there is only one company secret which is that Mr Cartley is being paid for five more drivers than he employs, with the surplus being shared between him and Red, the foreman and number one driver.

Patrick McGoohan gives a maniacal performance as Red, the foreman with whom Tom is destined to clash. His Irish brogue is in full flow as he swaggers around the yard with a cigarette hanging from his mouth. Red has a disregard for everything except money and his disdain for the highway code is such that he even manages to drink a bottle of beer and drive a truck at the same time. That takes some dedication, even in the free-wheeling 1950s.

Red is so confident of his driving abilities that he perpetually holds up a gold cigarette case as a prize for any driver foolhardy enough to try and beat the number of runs he makes in a day, He knows he is on to a sure thing because he is the only member of the crew crazy enough to take a short cut past the quarry.

The crew is made up of reliable character actors like Alfie Bass and George Murcell. You will know their faces if not their names. Also in the mix is the more recognisable Sid James. The Carry On favourite had not yet reached the stage in his career when every character he played was called Sid. In this one he is known as Dusty, a name that sounds reasonable only when it precedes Hare, Springfield or Bin.

Sean Connery and Gordon Jackson can also be found lurking in the background. They have surprisingly little to say for themselves but it is good to see Hudson getting his hands dirty before managing to secure a cushier billet at 165 Eaton Place.

At the start of the film Lucy is sort of involved with truck driver Gino, an Italian ex-prisoner-of-war played by Herbert Lom. Mr Lom gives a full-blooded performance as Gino which leaves the viewer in doubt that the character is Italian. He is courting Lucy with the intention of dragging her off to Italy so that she can pop out loads of bambinos and learn how to make pasta sauce just like his mama used to make.

Herbert Lom should have reined it in a little bit but I think he studied Patrick McGoohan’s performance and thought ‘Well, if he can get away with it, so can I’.

Lucy has unilaterally decided that Italy is not for her and she becomes instantly smitten with Tom. She makes no secret of the fact, but gentle Gino is too in love with her to notice that her thoughts are elsewhere. Her game of cat and mouse with Tom culminates in an erotically charged encounter amidst the oil and grease of Hawletts' yard. Gino is his best friend, but poor Tom just can’t resist temptation.

Most of the females on display are more than a match for the men. As well as Lucy, we have the landlady Ma West, played by Marjorie Rhodes, who manages the boarding house with a rod of iron. She also offers a laundry service on the side at thruppence an item.

I am indebted to the trivia pages of IMDb for pointing out that Stanley Baker wears the same shirt throughout the film. I had seen the film a few times and had never realised that. It is hard to tell in black and white but I’d say it is a shirt of a light blue colour with large, darker blue checks.

Ma West keeps the boys in check at the digs while the fearsome Mrs Yateley does the same with her two sons when Tom returns home for a catch up with his younger brother, Jimmy. She is a God-fearing woman and Tom wisely tries to time his visit to the family shop to coincide with his mother’s attendance at church. Either his or his mother’s timing is off because she arrives back to interrupt proceedings.

The conflict between mother and elder son makes for a bleak but compelling scene. Jimmy is going about on crutches and, reading between the lines, Tom is to blame for his predicament. Tom’s spirit is willing but his flesh is weak which meant he couldn’t say no to an earlier life of crime. You can’t say that Mrs Yateley doesn’t know her elder son. She realises his weakness and makes him pay for it. He tries to give some money to his brother but is prevented from doing so by his mother who sees it as a gesture aimed at salving his conscience.

For all his masculine pride, Tom’s mother has reduced him to a small boy, found wanting and unable to explain himself. It is no wonder that he makes a quick exit. He has probably reasoned that the set up at Hawletts may not be perfect, but it is a lot better than the dysfunctional living arrangements chez Yateley. It is his brother Jimmy I feel sorry for in all this, abandoned as he is to their mother’s tender mercies. Here’s to Beatrice Varley who puts in sterling work as the mother.

Brother Jimmy is played by David McCallum, former husband of Jill Ireland who also appears in the film as Jill. I am too young to remember Mr McCallum’s glory years in The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and my first TV memory of him is his appearance in the series The Invisible Man.

This lived up to its name because it disappeared from the schedules after just a few episodes. The same fate befell The Gemini Man, a similarly-themed series starring Ben Murphy which aired shortly afterwards. Perhaps invisibility is only an impressive superpower when it’s in the hands of Claude Rains.

Lucy, Ma West, Mrs Yateley, you can put any one of them behind the wheel of a two-ton lorry and she will be just as ruthless as the men.

There is a moment towards the end of the film when Carsley refers to Lucy as ‘that slut’. Even from this distance it is possible to hear the gasps of the cinema audience at such coarseness, quickly followed by the whisper that Lucy is no better than she ought to be so perhaps Carsley has a point.

I think the audience of the time would have found it much easier to sympathise with the more compliant Jill. She is a peripheral character who helps out at the boarding house and the greasy spoon and quietly has the hots for Tom.

Jill doesn’t have the oomph of the other three females, but I like to think that she would have the presence of mind to tell Tom to change his shirt once in a while. Tom’s personal hygiene aside, I fear that Jill is well on the way to learning an important life lesson which is that shy bairns get nowt. Lucy would be only too eager to teach her that one.

We all know it is coming but the fight between Red and Tom is a brutal affair. It is prompted by Red unfairly docking Tom’s wages to pay for some broken machinery. You can call a man a yellow-belly, you can even sabotage his truck, but you don’t mess with his money. What else are we working for?

One of the pleasures of watching a film like this is seeing what we did then that we don’t do now.

The viewer knows that Tom and Red are going to have some serious fisticuffs because they each take their coat off. Men always seemed to take their coat before duking it out. It would have allowed for freer movement of the arms but also, I think, it was a sign that each was giving the other a 'square go', as Hudson would have called it in his street-fighting Glasgow days.

We don’t do that now because if we did, well, there would be nowhere to hide the knives innit?

Most of the drivers favour those sleeveless leather jerkins that workmen don't seem to wear nowadays. I always imagine the workers in a Shakespeare play being similarly attired but the last person I saw wearing one of these was Stan Ogden. He used to put one on whenever he wanted to fool Hilda into believing he was going out to work when really he was up to no good down Inkerman Street way.

Tom eschews sleeveless workwear and favours a cool, timeless leather blouson. I would call it a bomber jacket but I don’t know if that would be correct, then or now. From the top half he looks a worldbeater but he is sadly let down by his choice of footwear. On his feet he wears wellington boots with the tops turned over so they look like ankle boots. The spirit of Jimmy Cricket looms large in such attire and the look can only be successfully worn with an 'L' and an 'R' on the wrong feet.

The drivers fill their spare time by going to village dances and playing tabletop football. Tom would make for an intense opponent in anything. I wouldn’t like to be on the winning side against him because he would be a surly and uncommunicative loser. On the other hand, I wouldn’t like to on the losing side against Red because he would rub my nose in it.

While the truckers are playing table football there is a shot of a poster advertising Jack Hylton’s Ring Out the Bells featuring The Crazy Gang. I would have thought The Crazy Gang would have been outdated even then.

I would feel relatively comfortable recognising Flanagan and Allen if only because of Underneath the Arches, Run Rabbit Run and that song about the Siegfried Line. I know the names of Nervo, Knox, Naughton and Gold, aka the other four in the Gang, but not the faces. It is surprising how persuasive a handful of songs are.

Jack Hylton is known to me only from a risqué limerick. The cast list varies but in the version I heard he appears with a young called Gloria, Gerald du Maurier and the band at the Waldorf Astoria.

Who gets remembered and who doesn’t? Ask me another. The punchline, which most of us willingly ignore, is that how we are remembered when we are gone doesn’t really matter because we won’t be around to feel the benefit anyway.

Having said that, I’m not proud. If given a choice between oblivion and a tenuous remembrance in a saucy verse, I know which box I would be opening. It makes me wonder though if the young lady’s career path would have turned out differently if she hadn’t been called Gloria.

I’d like to give a shout out here to Marianne Stone who, by 1957, was well into a career which saw her feature in every British film made between the end of the Second World War and the start of The Beatles. This isn’t true of course, but it feels as though it should be.

Ms Stone appears near the end of this one. She plays the earnest hospital nurse who sadly tells Tom and Peggy that there is no hope for Herbert Lom's Italian accent. It is beyond the help of the NHS so, if Tom and Peggy want to give him tips on how to say ‘Ciao’, now is the time.

The hell drivers work hard for their money and this makes Carsley and Red’s little racket all the more squalid. They both perish in the end when the lorry they are in tumbles over the edge of the quarry and bursts into flames.

Tom is luckier. His truck ends up balanced seesaw-like over the edge of the quarry, but he manages to scramble out of it before it topples to its destruction. The scene recalls the ending of the Italian Job in which the coach dangles precariously over a mountain top somewhere in the Alps or, closer to home, the stunt from Some Mothers Do 'Ave 'Em in which Frank Spencer and Morris Minor hang from a cliff somewhere on the Dorset coast.

Tom evades the clutches of the quarry and is reunited with Lucy. Perhaps he gets his glittering prize after all, but then again, she’s a strong-willed young lady so I don’t think it’s going to be all moonlight and roses. Tom and Lucy may not be headed for domestic bliss but the viewer can assume that, with the demise of Carsley and Red, the haulage yard at least will become a more equitable and harmonious place to work,

One of the things I learned long before the advent of Google is that, if you are even given the chance to watch Stanley Baker in action, you should take it. You look at him and you find yourself staring back at you. All the qualities, good and bad, that make us human, can be seen in him.

He would have been in his late twenties when he appeared in Hell Drivers, but he looks a good ten years older. I wonder if he knew he was in a race against time. He died of lung cancer at the age of 48 in 1976. I think of that when I see him puffing on a cigarette or when Red offers up the McGuffin of the gold cigarette case.

The director of Hell Drivers is better known as Cy Endfield, the man who directed another great Stanley Baker vehicle, Zulu. Which reminds me, I have a yearly Yuletide rendezvous with Mr Baker, the threadbare red line and the opposing Zulu army at the mission station at Rorke’s Drift, Natal. Men of Harlech, stand ye steady for I shall not fail that rendezvous.

Stanley Baker is impressive in full colour, baking under the hot South African sun but Hell Drivers shows that he is just as memorable in glorious monochrome.

I would highly recommend the film. It has been around a while now, but it has plenty of miles left on the clock. OK, so some of the characterisations are a little rusty, but it’s still a decent runner. It offers a breakneck trip through a gorgeous black and white Britain at a time when everything was accounted for in pounds, shillings and pence. The wearing of seatbelts is not compulsory but is strongly advised.

Published on January 8th, 2024. Written by Andrew Cobby for Television Heaven.