Trekking From Small Screen to Big Screen

“the moral of the story is that in adapting a successful television show for the cinema, it is obviously essential to be true to the show in its plotting and characters”

Trekking From Small Screen to Big Screen by John Winterson Richards

While there have been many television shows that were adapted into feature films for Cinema, and television spin-offs of feature films, Star Trek is the only major multimedia franchise that began in television. As such there has always been what one might call a degree of creative tension between the two main arms of what is often simply called "The Franchise," the televisual and the cinematic.

This is to an extent a technical problem in that both media have different objectives. A cinematic release has to stress its uniqueness: it requires a substantially free-standing plot, with a beginning, a middle, and an end, even if it is part of an ongoing series; it helps to have a distinctive visual style; there needs to be an element of novelty to make the journey from the couch to the cinema worth the effort.

By contrast, television relies more on continuity, especially in these days of long story and character arcs. Viewers often like just hanging out with old friends and tend to dislike dramatic changes in long established shows. They dislike it when films kill off characters and change "the lore."

This article is not so much a review of the six feature films based on the original Star Trek as a discussion of how they faced this technical problem, and also of the relationship between the films and the original television show.

Ever since the cancellation of the show in 1969, a number of people were campaigning for its revival, encouraged by the success of constant repeats in syndication and abroad. From the mid 1970s on, even before the success of Star Wars, Gene Roddenberry was working on a possible feature film. His screenplay did not find favour but by that point Star Wars had proved that science fiction was a viable market after all, so the abandoned film evolved into a television sequel, to be known as Star Trek: Phase II, starring most of the original cast. This was in turn abandoned when the success of Close Encounters of the Third Kind following that of Star Wars convinced executives that the big screen was the better medium after all, and the film was back on.

The first Star Trek feature film, subtitled simply The Motion Picture (1979), was put together very quickly by the standards of today's science fiction epics. Part of the explanation for that speed was the way Roddenberry and his team recycled many of the ideas, and even some of the sets, on which they had been working when preparing Phase II.

From what we can deduce from these, Phase II was no great loss. It seems to confirm the impression that Roddenberry himself had a poor commercial sense and never quite understood what had made his greatest achievement so popular. Much of the emphasis was to have been on two new, younger characters - who seem in retrospect to have much in common with Will Riker and Deanna Troi in Star Trek: the Next Generation which came out almost a decade later - the old favourites taking more of a supporting role.

The bright lighting and primary colours of the late 1960s were replaced by the supposedly more sophisticated subdued tones of the late 1970s. The colour palette seems to have been limited deliberately in imitation of Star Wars. This aesthetic, along with some sets and the two young characters, were transferred to The Motion Picture - and detracted from it.

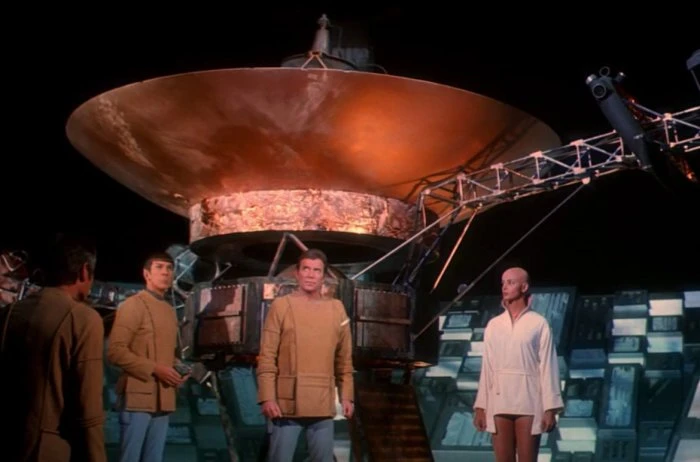

There was a similar lack of originality in the plot. The premise came straight from The Changeling, a memorable but mid-level second season episode of the original television series - which handled it better: a probe launched from Earth long ago returns, having been reprogrammed in a way that causes it to destroy life on a massive scale. Needless to say, no one in the film mentions that they have dealt with a similar situation before.

In The Changeling the probe is the wholly fictional Nomad. In The Motion Picture it is V'Ger, a fictional continuation of the real life Voyager probes which has just been launched at the time the film was being made. The rather clever idea at the heart of the film is that an original Voyager probe has become the centre of a massive accumulation of Space junk which is on the edge of sentience. Although the film gives a good impression of its scale, it is still not as frightening as Nomad - there was something particularly chilling in the fact that Nomad looked and sounded like a traditional cute robot, which made it all the more disconcerting when it suddenly killed without remorse. A scene where Nomad is floating casually around the Enterprise and all the crew are nervously trying to ignore it is still particularly effective.

The script pads the story by having Kirk, now an Admiral, take personal command of the Enterprise, which is being refitted, in order to save Earth from V'Ger. Things do not go well. The two juvenile leads are subsumed by V'Ger - possibly prefiguring Borg assimilation - but Spock does some Vulcan stuff and Kirk declares victory by claiming that incorporating the humans into V'Ger means it is a new life form, so they are not really dead. Hmm...

And that is basically it. That was the long awaited and very expensive return of Star Trek. It would have made a very inferior episode of the original show, and is indeed much inferior to The Changeling. The film has little action and no real antagonist. Even Nomad has far more personality than V'Ger. The juvenile leads added nothing and their loss had no emotional impact, except that it nevertheless struck a flat concluding note that Kirk listed them as missing and then did not rescue them as a hero is supposed to do. To be honest the whole film is far from Kirk's finest hour: he comes across as a Peter Pan figure, the little boy who would not grow up.

The script was evidently trying to be cerebral, more Close Encounters of the Third Kind than Star Wars, but the television show had demonstrated how it was possible to combine intelligent ideas with action. That skill seemed to have been forgotten. Moreover, for a supposedly cerebral film, The Motion Picture has little depth. Many of the best episodes of the show had managed to ask far more interesting questions and provoke far more stimulating thoughts in just 50 minutes than the feature length film in two long hours.

All this was combined with a visual style that was the opposite of what had been so attractive about the show and what long time fans wanted to see again. There are some impressive sequences, such as the much-imitated initial approach to the Enterprise, and Jerry Goldsmith's score set a new standard, but there is no denying that overall, The Motion Picture showed that Roddenberry and his team had not grasped what it took to fill the big screen and the longer running time. Critics and fans were disappointed.

Nevertheless, contrary to legend, The Motion Picture was a box office hit, thanks mainly to the Star Trek brand name, and it made a reasonable profit, if not as much an anticipated due mainly to the very high production costs. The studio executives came to the correct conclusion, for once, that there was still money in that brand name and resolved to carry on with a Star Trek film series.

Roddenberry was, not for the first time or the last in the history of "his" franchise, effectively sidelined in it. The success of the second Star Trek film, The Wrath of Khan (1982) owes more to the vision of its director, Nicholas Meyer. An outstanding novelist, a talented scriptwriter, and a successful producer as well as a skilled director, Meyer is one of the very few genuinely multitalented people operating in Hollywood in recent years. Everyone these days likes to think of himself as a "triple threat" hyphenate - "writer-director-producer" or whatever - but Meyer is the real deal. Yet, whether by choice or circumstance, he is rarely involved in a production in multiple roles: he may be the author of the novel on which one project is based, the scriptwriter for another, and the director of a third, but not all three at once. As a result, he has never been an "auteur" director and is not as well known as he deserves. Perhaps the very diversity of his talents has spread him too thin, but every project in which he is involved is at least interesting and his forays into the Star Trek universe have always been welcomed by fans.

Credit must also be given to Harve Bennett, who helped come up with the story for The Wrath of Khan, reportedly after watching the whole original television series - it certainly looks as if someone knew their Trek. Bennett was to contribute to the plotting of the three subsequent films, providing a much needed element of continuity.

Many, probably most, fans consider The Wrath of Khan to be the best of the Star Trek films and the standard by which the others are judged. Produced far more cheaply than The Motion Picture, it was a huge financial success and set Star Trek properly on its feet as a film franchise. It was the first of a trilogy of films with its own overall story and character arcs in addition to the self contained stories of each of the three films.

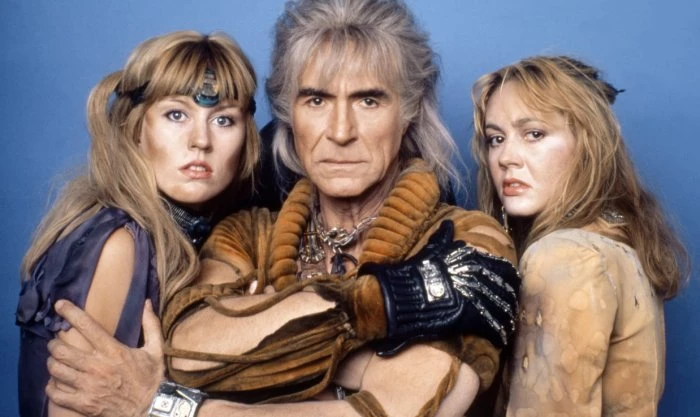

Like its predecessor, The Wrath of Khan references an episode of the original show, but where the The Motion Picture was in effect a "reboot" of The Changeling, its sequel was more of a sequel to the well regarded episode Space Seed. This is the one in which Ricardo Montalban played a 20th Century dictator, the eponymous Khan, who had tried to take over the Enterprise on emerging from stasis. The episode had ended on an optimistic note with Kirk leaving Khan and his associates on a deserted planet, confident that people of their superior abilities would relish the challenge of building their own brave new world there.

The film catches up with them and it turns out that Kirk's confidence was badly misplaced. The planet in question is a living Hell, not a brave new world, and Khan, presented as an ambitious but noble character in Space Seed, is left embittered. He yearns for revenge against Kirk in particular.

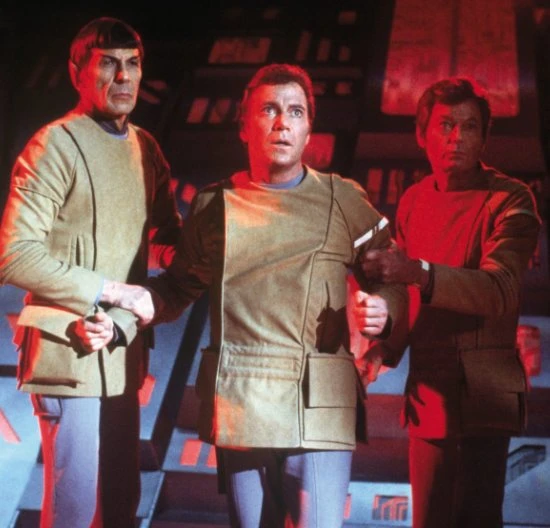

The story that follows is small scale. The future of Mankind is not an issue. It therefore feels a lot more like an extended episode of the television show. It helps that there is a deliberate attempt to get back a bit closer to the visual style of the show, with more light and brighter colours. There are good action sequences but enough space is left for character moments.

However, the great strength of The Wrath of Khan is that there are proper emotional stakes on the table. It turns out that Kirk has a son we never met before - probably best not to get too fond of him. After a game of complicated manoeuvres, bluff, and double bluff, Kirk prevails, but this time he pays a real price for his victory. He loses his best friend Spock in a scene that has since become a classic and which has more power than anyone has a right to expect from a supposedly silly science fiction adventure.

This left the problem of where to go from there. The title of the third Star Trek film, The Search for Spock (1984), rather gave it away - and immediately undermined the emotional impact of the previous film.

You see it turns out that the souls of dead Vulcans can be recovered in some way.

Who knew?

No one who had watched the television show for starters. There was no hint of it there. The Vulcans were presented there as like humans but better, a standard to which humans might aspire. To suggest they were somehow immortal missed the point entirely. Apart from anything else Spock's moving self sacrifice was substantially devalued.

The way this clumsy plot device came out of nowhere tainted the film from the start, which is a pity because there is a lot of good in The Search for Spock if one can overlook the conceptual flaws. Bennett's script has a lot of true Trek in places. Relieved of acting duties for the most of the film, Leonard Nimoy took the director's chair and his light touch was the complete opposite of the portentous pomposity of The Motion Picture. He showed a particular gift for comedy - McCoy's reaction to Spock's soul taking over his mind is hilarious. There are also some real emotional moments, above all the loss of the Enterprise itself. To be honest it is rather thrown away and things are never quite the same after that. Christopher Lloyd excels playing it straight as an ambitious Klingon who gets in the way of the gang's quest to resurrect their friend - and seems to have become a prototype for future Klingons.

Nimoy's style was even better suited to the fourth Star Trek film, The Voyage Home (1986), which took a more light-hearted tone throughout. Co-scripted by Meyer, it concludes the trilogy that began with The Wrath of Khan. Although each is a separate story, in the second and third parts of the trilogy our heroes must cope with the consequences of what happened in the previous part. In The Voyage Home they must face a reckoning for having stolen a starship to search for Spock.

Happily for them, if not for the rest of the human race, this is postponed by another probe threatening Earth - which seems to be a bit of a thing in the film series. It turns out that it can be redirected only by humpback whales which are sadly extinct by this point. Whoops. Serves us right.

This is, of course, a convenient excuse for a bit of time travel back to 1980s - what a coincidence - and a reference to the television series, where it was shown to be possible due to the "slingshot effect" discovered by accident in the episode Tomorrow is Yesterday and used again in the episode Assignment: Earth. This plot device is something of an embarrassment, and the franchise has generally ignored it ever since, but it is "canon." Once we are back in the Eighties, the tone is one of almost unbroken jollity, despite some tense moments including Chekov getting shot and being treated by what McCoy considers the barbarities of 20th Century medicine.

Back in the 23rd Century, our gang are simultaneously punished and rewarded for saving the world (again) by being ordered to go back to what they used to do except in a brand new Enterprise.

That might have been a good moment to wrap up the film series with a happy ending and the sense that our heroes' journeys had come full circle: the classic "hero's journey" is complete only when the hero returns "home," and home for Kirk and his friends in The Voyage Home is a starship.

However, the financial success of The Voyage Home meant that was not really an option. The fifth film in the series, The Final Frontier (1989), is freestanding, and owes little either to the previous films or to the original television show. Its premise is potentially an interesting one: a Vulcan religious fanatic takes hostages because he wants a starship to search for God.

Roddenberry, while not identifying as an atheist, famously disliked any mention of religion in Star Trek. There are occasions when this seems like a glaring omission, when themes are addressed which would provoke religious reflection and speculation almost as a matter of course, but when the script seems to tiptoe around the elephant in the room. The Final Frontier charges straight at it - and then rather sidesteps it at the last moment.

The question of Vulcan attitudes to religion might be particularly fascinating to explore. The Vulcans are a strictly logical people, so how do they deal with a concept like the existence of God for which there is - barring some currently unforeseeable discovery, or revelation, between now and the 23rd Century - no absolutely conclusive evidence one way or the other? We know, most memorably from the original series episode Amok Time, that the Vulcan obsession with logic is actually supressing passionate emotions. Might they also be suppressing a deep Spirituality? The events in The Search for Spock, rich in Christian symbolism, certainly imply as much.

Sadly the script ignores these issues completely. It is a great opportunity wasted. Instead we get the Enterprise going off to meet a very powerful entity which claims to be God - only to have these claims exploded when Kirk asks an obvious question.

The annoying thing about this is that anyone familiar with the original television show knows that the characters would be well aware of the possibility that a species or entity with superior power and knowledge would appear God-like to lesser, or less developed, beings. It was a theme explored in several episodes, most directly in Who Mourns for Adonais? One might therefore have taken it for granted that the very first question Kirk and crew would have asked was whether the higher intelligence with which they were dealing was necessarily the Supreme Being.

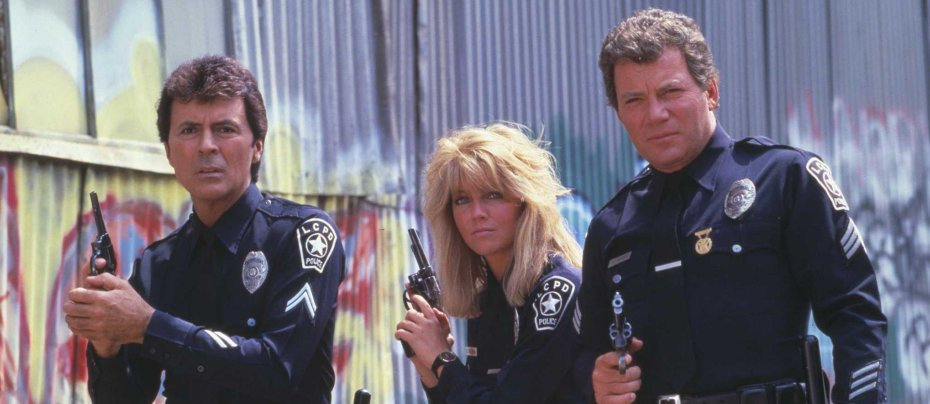

As with The Search for Spock, this major conceptual flaw in the plotting spoils a film that is, in other respects, not entirely without merit. William Shatner, taking over the director's chair from Nimoy, brought a more realistic, less glamorous visual style to the production. It worked well, at least in places, even if some of the effects could have been better. Shatner also delivers some of the best character moments in the film series and shares Nimoy's deft touch with humour. It helps that by this stage the cast were completely comfortable in their roles and with each other, which had not always been the case to put it politely.

There is a definite air of valediction about The Final Frontier, not least in the title. However, if the success of The Voyage Home had made one more trip to the well irresistible, the failure of The Final Frontier had the same effect, even if for completely different reasons. There was a feeling that things could not simply be left there and that the original Star Trek deserved a better resolution. Apart from anything else, major investment in The Next Generation at this point meant the brand name had to be protected from association with defeat.

So it turns out that beyond The Final Frontier there is indeed The Undiscovered Country - which was the subtitle of the sixth Star Trek feature in 1991. Nicholas Meyer returned as director and co-wrote the script. The premise was a very unsubtle reference to then current events, the end of the Cold War following the Chernobyl disaster - or, in the Trek universe, the Klingons seeking peace after an environmental disaster of their own.

Not all are happy at the prospect of peace. Just as Soviet hardliners launched a coup against Gorbachev the year the film came out, so Klingon hardliners plot against the peace-seeking Klingon Chancellor played by David Warner. Kirk himself is not so keen on reconciliation. This is totally in keeping with the Cold Warrior he was the original television show and since then the films have given him additional reason to dislike Klingons. It makes him the perfect fall guy when the peace talks are sabotaged by an assassination and he ends up on a Klingon penal planet. Needless to say his old comrades have no intention of letting this stand.

Meyer gets the balance between action and conflict of ideas just right. Although the film keeps up a brisk pace, it manages to fit in a lot of character development and relationship drama. Meyer builds on Shatner's introduction of a more realistic visual style. This looks like an Enterprise that might have a distinct smell about it. Christopher Plummer enjoys himself as a Shakespeare spouting Klingon who relishes being the villain while retaining an internally consistent point of view. The whole thing should be studied as a textbook example of how such films should be done.

William Shatner returned as Kirk in the seventh Star Trek film, Generations, but, as its name suggests, that was really the first cinematic outing of The Next Generation not the seventh of the original cast - and is perhaps a story for another day.

For all intents and purposes, what was by them becoming generally known as "The Original Series" ended with The Undiscovered Country and it would be difficult to conceive of a more suitable conclusion.

It was already becoming axiomatic among fans by that stage that the even numbered Star Trek films were better than the odd numbered ones. That is certainly true of the first six, even if the gap between them is not as great as some maintain: while flawed, The Search for Spock and The Final Frontier both deserve more respect than they usually get.

There is, however, something else that distinguishes the three undeniably great Star Trek films from the three disappointing ones. The three greats were the ones that showed the greatest awareness of the original television show: The Wrath of Khan was a direct sequel to one of its episodes; The Voyage Home used technology familiar from the show; and The Undiscovered Country built on Kirk's character as it was revealed in the show. These direct references suggest a greater general knowledge of the Star Trek "canon" which also comes across in other aspects of these films such as the interplay of characters. By contrast The Motion Picture feels like generic science fiction, and while The Search for Spock and The Final Frontier do have some nice Trek moments, they are not enough to make up for the inconsistency with the show in their plotting.

The moral of the story is therefore that in adapting a successful television show for the cinema, it is obviously essential to be true to the show in its plotting and characters, but it is almost as important to try to replicate the "texture" of the show, the sense of depth that is built up over many episodes. This texture is an elusive concept, so it is no surprise that cinematic adaptations rarely get it right, and the Star Trek franchise deserves credit for achieving it more often than most and at least as often as not.

Published on June 7th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.