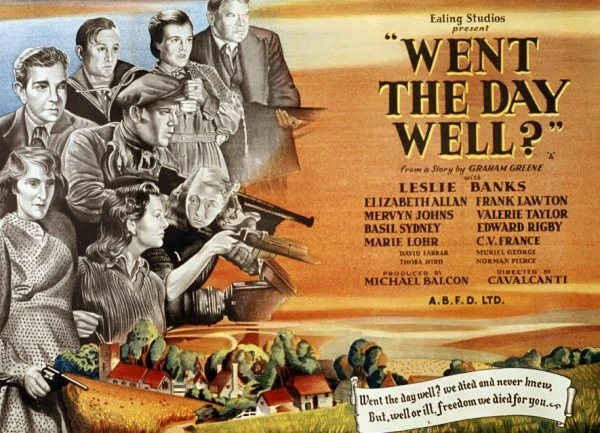

Went the Day Well?

or Women and Children First

by Andrew Cobby

If you’re ever in the village of Bramley End, which you’ll find near Dibley, have a look for the monument dedicated to some German soldiers in the church graveyard. If you’re lucky, Mervyn Johns might take a break from tending the graves and tell you all about it.

The film was made in 1942 by Ealing Studios. It is a story of war but told from an unspecified point in the future, when the war has been won and the sacrifices have been worthwhile.

Unusually for a war film the fighting doesn’t take place in a foreign field, it happens in England’s green and pleasant land. It is an Ealing film, after all. It contains scenes of shocking violence that have the power to disturb even to this day.

If it is this powerful now, imagine how an audience would have felt watching it during the Second World War. We haven’t had time to get to know them but, when the Home Guard are ambushed and killed in the country lane, the sight is as horrific as witnessing the magnificent seven of Walmington-on-Sea being mown down in front of Timothy White’s.

Surprisingly for a war film, its most powerful scenes depict violence being inflicted on, and by, women. The shopkeeper, the vicar’s daughter and the lady of the manor are all pulled into the conflict raging on their own doorstep. Women are in the thick of it and all of them give as good as they get. Potential wrong-doers will find to their cost that there are plenty of strong and resourceful females down Bramley End and Dibley way.

The residents of Bramley End are excited to see the arrival in the village of a detachment of British Army sappers, commanded by the urbane Major Hammond. Unknown to the villagers, they are not the British Army at all but a division of German paratroopers intent on paving the way for the invasion of England.

Bramley End is a typical English village, prone to petty rivalries and squabbles as everyone jockeys for position. Nora, the vicar’s daughter is in gentle competition for social standing with the older Mrs Fraser. The contest moves up a notch when the soldiers arrive and they both strive to bag the Commanding Officer for a house guest. Nora wins that round.

Shopkeeper Mrs Collins may be foolish at times – she apparently thinks at one point that scarecrows were signalling to the enemy. She is not a bad sort, though, because she takes her ribbing over this with good grace and proves herself to be a very brave lady.

Rounding out the distaff side are Mrs Collins’ young assistant Daisy (Patricia Hayes), Peggy who is due to be married to sailor Tom Sturry, and her friend Ivy.

Early on in the film, one of the soldiers gives young George a twisted ear for taking a peek at the equipment on the truck and is rebuked by the post mistress Mrs Collins as being no better than a German. I would have been tempted to give the lad a fourpenny one too, on the grounds that this is still the 1940s, young man, and children should be seen and not heard.

Had I taken such a high-handed attitude with young George, the joke would have been on me because George and the other evacuees show a resilience way beyond their years. George it is who sneaks out of the manor house, evades the sentries and eventually manages to raise the alarm at the next village, taking a bullet to the leg for his trouble.

It is a fabulously mature performance from a 16-year-old Harry Fowler as George. Check him out too in the slightly later film Hue and Cry, a tale of street gangs, criminals and coded messages in children’s comics. Don’t worry, the film is a lot better than I have made it sound and, here be spoilers, Jack Warner even gets to stretch himself by playing a villain for a change.

Mr Fowler developed into a respected character actor but my only memory of him from my youth was his participation in Going a Bundle, a kids’ TV show about people collecting things. He was joined in this by Anne Aston, taking a sabbatical from adding up on The Golden Shot. Going a Bundle was produced by Southern Television and, as Talking Pictures appears to have bought up this company’s entire output, it is a fair bet that it’ll be coming soon to that platform.

There are various hints that the British squaddies are not all that they seem. They sometimes give abrupt and unexpected answers to questions and they write some of their figures in the strange, continental way.

They are in a strange land so it is to be expected that they give themselves away. The past is another country and I wonder how I would fare if I was teleported back to the England of 1942. Anyway, to be fair to the fake squaddies, I didn’t know there is a Piccadilly in Manchester, either.

Nora is the first to suspect. Her female intuition is set off by the unusually written figures and the discovery of a bar of chokolade from Wien found in Major Hammond’s bag.

The Germans think they have an ace up their sleeve in the shape of fifth columnist Oliver Wilsford. He is their chief collaborator but he is also the local Squire and object of Nora’s affections. She fancies him, in her quiet English way, as indicated by the quick re-arranging of her hair in the mirror when he makes an unexpected house call.

It isn’t long before Nora’s female intuition is firing on all cylinders because she even starts to suspect Squire Wilsford. Of course, her feelings for him persuade her that she is wrong until she gets irrefutable proof when she and Mrs Fraser spy Wilsford conspiring with the Germans.

Mainly because of Nora’s suspicions, Major Hammond is forced to whip off his mask and reveal himself to be dastardly Major Ortler, Nazi interloper of this parish.

The villagers are held captive in the church and the vicar, Nora’s father, is shot dead attempting to ring dem bells and raise the alarm.

The German soldiers have revealed their true selves and this is when the women folk do likewise.

Mrs Collins throws pepper in the eyes of her unwanted German lodger, grabs a hatchet from the hearth and quickly dispatches him. It is a scene of sudden and unexpected violence and Mrs Collins’s reaction to the killing conveys the emotional toll of the situation. She knows that, in killing the German soldier, she has sacrificed herself.

After killing him she frantically tries to get through to the outside world via the telephone line. She is put on hold by the gossiping telephonist at the other end who sees that the caller is ‘only old Mother Collins’. The jibe is cruel in more ways than one.

Before swinging the axe she explains to the soldier that she was unable to have children. The soldier replies that he is unmarried but has two strapping sons who will soon be of fighting age. I can’t help thinking that this revelation helped to seal his fate.

The end for Mrs Collins is quick and sharp. The viewer knows that the poor lady won’t be able to avoid her fate but it’s still horrifying when it comes.

Her assistant Daisy doesn’t kill anyone or get herself killed but she has a moving moment of mental collapse. How do you cope with the sudden violent death of someone you see every day or witness the death of a stranger at close quarters? You try and survive the best you can and no one has the right to judge you on that.

That Thora Hird is a game girl. As Ivy she cheerfully positions herself by the window of the manor house with a loaded rifle and takes aim. It only confirms what I always suspected of good old Thora - give her a gun and she’ll take potshots at anything. Went the Dame well? She surely did.

Her mate Peggy does the same thing but, for some reason, I don’t find Peggy as memorable. I have nothing against the actress Elizabeth Allan, who plays her, but she displays a similar blandness in the otherwise marvellous film Saloon Bar made in 1940.

Mrs Fraser, played by Marie Lohr, at first appears to be a pompous and over-refined old lady. She loses out to Nora in the battle to bag the Commanding Officer, but she re-asserts her authority by organising the billets and hosting a dinner party for the newcomers.

I could have done with seeing more of her Cousin Maud and her dog Edward. All praise to Hilda Bayley, who plays Maud, for making the most of a small role.

Maud driving along in her car singing the old English song Cherry Ripe and ticking off the dog is a wonderful and unexpected addition to the film. Apart from the intro and outro, it is noticeable how very little music there is to be heard, incidental or otherwise.

It is strange how a song can achieve different effects. Cherry Ripe has a haunting tune which is used to almost comic effect here, but the air only adds to the eerie atmosphere of the séance scene in Night of the Demon.

For all her self-importance, Mrs Fraser shows a remarkable tenderness towards the evacuees, and a fearsome bravery during battle. She talks the talk but she also walks the walk, shielding the children and taking the full force of a hand grenade tossed into their midst. Just as we were getting to like the old girl too.

The most potent scene is the one in which Nora, the vicar’s daughter, shoots and kills Oliver Wilsford. The viewer is expecting some tense music to accompany Nora as she makes her way purposefully down the stairs with gun in hand. The only accompaniment we hear is the voice of Tom Sturry, instructing Ivy and Peggy on how to use a rifle.

There are no pot shots here, no wasted ammunition. This is shoot to kill. Nora trusted Wilsford, perhaps even loved him, but he is a collaborator who is responsible for the death of her father. He didn’t pull the trigger, but he may as well have done. The Squire has not only betrayed the village and the country, he has betrayed her.

When a stricken Wilsford falls from on high, from his pedestal, he does so in slow motion. It is an unusual technique to employ but it leaves a powerful impression. I don’t know why it should be that watching something unfold in slow motion tends to quicken the heartbeat.

Nora performs a cold-blooded execution but, similar to the killing carried out by Mrs Collins, she can’t defy the physical and emotional backlash that must be part and parcel of taking another person’s life.

She knows how to handle a revolver ‘well enough’ but she doesn’t realise how heavy a handgun feels to someone not used to carrying one or the physical recoil that results from firing a gun.

It takes Nora 50 seconds to pick up the revolver, descend the staircase and shoot Wilsford (yes, that’s right, I have timed it). It plays out like a time-bomb and the viewer can hear the tick, tick, tick before the inevitable explosion.

There is no time to look away. The spectacle is a relentless depiction of quiet resolve but it also demonstrates that, with some of us, there is more going on behind the eyes than the casual observer would ever suspect.

A long-range death from a rifle elicits a gleeful smile from those pulling the trigger. War has become an amusement arcade as another one bites the dust. The actions, and reactions, of Mrs Collins and Nora let the viewer know that when killing is up close and personal, it’s a different ball game.

The invaders expected a capitulation but all they got was six feet of the country. That is all any of us is entitled to, either buried under it or scattered somewhere over it.

The film is based on a short story, The Lieutenant Died Last, by Graham Greene. I haven’t read the story so I can’t vouch for the fidelity of the film. Graham Greene probably lags behind Agatha Christie and Stephen King in the list of most cinematic writers ever, but not by much. I have seen a fair few films adapted from his writing and Went the Day Well? is by far my favourite.

I have always been a frequent visitor of bookshops and I remember in the early 1990s Mr Greene’s name would often appear on books by an assortment of authors underneath a gushing blurb announcing the author as Mr Greene’s most favouritest writer in the whole wide world.

I learned to take his recommendations with a pinch of salt and I used to imagine him phoning in his latest recommendation while sunning himself at his home in the South of France. I was young and my suspicions about his artistic integrity put me off reading his books. Circumstances alter cases. Graham Greene is dead now and I have grown up a little. I am a fan of Richard Attenborough’s performance in Brighton Rock so I decided to give its pages a turn. ‘A good read. Preferred the film, though’ would be my blurb for that one.

I am a proud Teessider and Brighton Rock gets a bonus point for giving a name check to Middlesbrough. It is in good company because it is only the second book I have read, after The Diary of a Nobody, to do so. I’m not a literary critic but if given the choice between reading Brighton Rock or The Diary of a Nobody, choose the latter – it’s much funnier.

Similarly, I am no film critic but if you have to choose between watching Went the Day Well? or just about any other war film, choose the former. For all its 1940s monochrome and English village setting, there’s a good chance it will be far grittier.

Published on February 25th, 2024. Written by Andrew Cobby for Television Heaven.