Star Trek

1966 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards, Peter Henshuls, Laurence Marcus

If American television has given birth to a genuine phenomenon, it was the brainchild and labour of love of a former World War Two pilot, LAPD patrolman, and jobbing scriptwriter by the name of Gene Roddenberry. When, in 1964, he registered the initial treatment with the Writers' Guild of America, he decided, for the time being and for want of a better name, to call it Star Trek.

As a freelance writer, he had learned his craft on the likes of Highway Patrol and Have Gun - Will Travel. The last was a popular Western series about a gentleman gunslinger, played by Richard Boone, who travelled from place to place, and is probably best known for its catchy theme song. The Western genre, and its emphasis on that travel from place to place, obviously had a big impact on Roddenberry and 'Star Trek.' He was particularly influenced by two Western shows on which he had not worked, the hugely successful Gunsmoke and Wagon Train, which showed the pioneering ethos of the Old West as a series of regular cast members, led at first by Ward Bond, make their way across America, exploring new territories, making new discoveries, and pushing back boundaries. It is not difficult to see the similarities in Star Trek.

The other major influence is perhaps more surprising. The 1964 treatment drew heavily on C S Forester's fictional British naval officer, Horatio Hornblower. A daring seaman, Hornblower's courage and intelligence made him the perfect role model for the hero of Star Trek - Captain Robert April of the interstellar spacecraft 'S.S. Yorktown.'

As usually happens, there were changes, not least to names and format, in the subsequent development process, but one of the things that Roddenberry retained from Forester was the importance of a naval hierarchy, a crucial distinction from his Western influences.

The project was picked up by Desilu Productions, the leading independent production company founded by husband and wife Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball ("Desi-Lu" - that sort of thing was very popular in the Fifties). The complete opposite of the airheaded character she played in I Love Lucy, Ball was a serious player in "The Industry" at a time when it was almost entirely male dominated: if there was a woman in a Hollywood Board Room, she was probably there to take notes - unless she was Lucille Ball.

A pilot was made, 'The Cage,' featuring the more familiar 'U.S.S. Enterprise' under its famous Captain - Christopher Pike.

In something of a casting 'coup,' Pike was played by the high profile motion picture actor Jeffrey Hunter, who had portrayed Jesus in 'King of Kings' and been John Wayne's sidekick in arguably the greatest Western ever made, 'The Searchers.' The cast also included two actors with whom Roddenberry had worked before. Leonard Nimoy was Spock, but not Spock as we know him - there is actually something very disconcerting about seeing him grin. Majel Barrett, a classically attractive woman who was Roddenberry's mistress by this point, was Pike's second-in-command. This turned out to be too much for test audiences, so she was afterwards demoted to Nurse for the rest of the series, that being seen as a more appropriate role for a woman at the time.

Despite a fine performance by Hunter, the network, NBC, rejected the pilot: wary executives thought it "too cerebral," which tells you all you need to know about network executives. It was later cannibalised for clips in a two-part episode of the eventual series, 'The Menagerie.' For, as we all know, the story did not end there. NBC had nevertheless been impressed by what they saw, and such was Roddenberry and Ball's belief in the concept that, sweeping all opposition aside, they managed to get the network to greenlight a then unprecedented second pilot.

After a lot of shifting through potential scripts which later became episodes, Roddenberry selected 'Where No Man Has Gone Before.'However, there was a marked reluctance on the part of "above the line" talent to commit to a show that had already been rejected once. With Hunter bowing out, well known and viewer friendly names like Lloyd Bridges and Jack Lord passed on the leading role. Ultimately, it was almost by default that the respected young Canadian actor William Shatner took the helm as - at last - Captain James Tiberius Kirk.

While it was sufficiently successful to secure an order for a full season, 'Where No Man Has Gone Before' was not the first episode to be shown, at least not in the USA - it was in Britain. This makes it look something of an oddity because it is obviously a transition between the first pilot, 'The Cage,' and the regular series. So the visual style is not yet fully established and the Medical Officer is Dr Mark Piper, played by the hard working veteran Paul Fix.

The first episode shown in the States is the first of the series proper, 'The Man Trap.' By the time it was shot, DeForest Kelley, as Dr Leonard McCoy, had taken over the role of the Medical Officer. The core triumvirate was now in place. Although it does not seem to have been Roddenberry's original intention, the focus shifted from the traditional Hornblower-like action hero to a far more interesting interplay between three archetypes - the testosterone filled leader Kirk, the ruthlessly logical Spock, and the crusty but compassionate McCoy. Sometimes it is as if Spock and McCoy - Reason versus Emotion - are battling for Kirk's soul. At other times, it is a reflection of the struggle we all feel inside us, as our higher thoughts and feelings, both rational and humane, try to control our animal nature.

Yet that animal nature is necessary because, as Kirk discovers when he loses it in the episode 'The Enemy Within,' he needs it to be the decisive leader that he is.

That is a good example of the sort of intellectual issues raised by the better episodes of what was meant to be an action adventure show. The scripts are extraordinarily talky for a modern television drama of any sort in which the motto is "show, don't tell." Most unusually, you can listen to them as if they were radio plays with little loss of understanding of what is going on. They are actual literature. Roddenberry, a workmanlike writer himself, commissioned scripts from people of much greater literary talent, including Harlan Ellison, Gene Coon, Robert Bloch, Richard Matheson, Norman Spinrad, Theodore Sturgeon, and Dorothy Fontana, who started as Roddenberry's script assistant but went on to write some of the best loved 'Star Trek' scripts as D C Fontana. Apparently she used her initials because she was concerned that she might not be taken seriously if it was known that she was a woman, scriptwriting then being almost as much a male preserve as the business side of "The Industry."

It should be noted that the writing of 'Star Trek' was not done in a vacuum. Coinciding with the start of the Space Race, there had been something of a revolution in American science fiction over the previous decade. While it was still a genre of little prestige, distinguished more for quantity than quality, it was almost inevitable that the sheer bulk of cheap paperbacks and short story magazines was enough to generate a critical mass that began to crackle and fizz with energy and new ideas.

This had already been reflected on television in imaginative scripts for the likes of The Outer Limits and The Twilight Zone. The individual episodes of Star Trek, all of them free standing with no connecting story or character arcs, as was standard in television drama at the time, was therefore only a continuation of an established trend.

Yet it took the trend to a new level by using the familiar characters of Kirk and his crew to link what are basically short stories. When people discuss major themes found in science fiction, and sometimes even science fact, they tend to reference 'Star Trek' episodes, because everyone knows them. In 'Darmok,'an episode of the later Star Trek: the Next Generation, an alien species communicates using an idiom based on its traditional stories. To a great extent the human race itself does the same and the better known episodes of the original 'Star Trek' now count as being among our shared traditional stories.

Thus when discussing the possibility of parallel or multiple universes - now a respectable theory in modern cosmology because our own universe looks so unlikely on its own - one tends to think immediately of the 'Star Trek' episodes 'The Alternative Factor' and 'Mirror, Mirror' (fondly remembered as the one in which Spock has a beard). Discussions of predestination, historical inevitability, and the theoretical problems of time travel prompt thoughts of the episodes 'Tomorrow is Yesterday' and the acclaimed 'The City on the Edge of Forever,' in which Kirk falls in love with a saintly missionary played by Joan Collins but must watch her die rather than see the timeline disrupted.

The Jungian dichotomy of the personality, the notion that we all have a "shadow self" at odds with who we think we are, is explored in several episodes including 'Amok Time,' 'The Enemy Within,' and, again, 'Mirror, Mirror.'

Contemporary issues were also addressed. The Cold War was a frequent theme. In 'The Doomsday Machine,' a giant planet eating computer becomes the physical manifestation of the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction. Although the "special effects" might raise a smile today, it was actually very frightening to a child being brought up when the possibility of nuclear annihilation was always only a few minutes away. Even worse than the totality of the destruction by the machine was how impersonal it was. That is how a nuclear war would have been, a clash of computers.

This was an idea explored previously in an episode which is, if anything, even more chilling, 'A Taste of Armageddon.' Here war has become so ritualised that, in order to prevent the physical and cultural damage of actual attacks, those designated as killed in what are basically computer games step obediently into suicide booths. The alternative is presented in 'Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,' in which a civilisation is destroyed by irrational racial hatred. Meanwhile, 'The Mark of Gideon' is a graphic warning about overpopulation.

Although Roddenberry wanted to project what he saw as an optimistic vision of the future, 'Star Trek' stopped off at some very dark places along the way. This was balanced by a number of more light hearted episodes, including 'The Trouble With Tribbles' and 'A Piece of the Action.' In the last, Kirk imposes what is in effect a 40% tax on a civilisation modelled on 1920s Chicago. It is not the first time or the last that he ignores the Prime Directive of non-interference by which he was supposed to be bound.

Kirk was modelled on John F Kennedy, or rather on the idealised image of Kennedy that prevailed for many years after his murder. Like Kennedy, he promotes a "liberal" image but is in practice more pragmatic. Like Kennedy, he is against intervention - except when he is not.

Some commentators claim, retrospectively, that there is a political subtext to 'Star Trek,' especially in relation to the Vietnam War, but it is difficult to see. While Roddenberry, like most of Hollywood, tended to drift to the left of the American mainstream, the networks were far more powerful than they are in today's multi-channel, multi-platform marketplace and they were in turn influenced directly by the big advertising agencies. They vetted scripts very closely to ensure nothing was broadcast that might offend any large segment of consumers. It was only after the Tet Offensive in 1968 that American public opinion began to shift against the Vietnam War, and only after the election of Richard Nixon later the same year that Democrats, the majority in Hollywood, tended to become more actively opposed. Before that, with a Democrat in the White House, they had felt obliged to be more supportive of an involvement which had, after all, been initiated by Kennedy. So there is simply no denying that Kirk was, like Kennedy, an aggressive Cold Warrior - against Klingons and Romulans rather than Russians and Chinese - who was more than happy to get involved in conflict when it suited.

Indeed, the original 'Star Trek' was, culturally and, in some ways, politically, a very conservative show. Roddenberry chafed at this. It was only when he came to make 'Star Trek: the Next Generation,' that he was able to present his vision exclusively, because it was sold directly into syndication without going through the networks at all. The exclusivity of this vision could be one of the reasons why 'Star Trek: the Next Generation' may have greater "cult" appeal to fans but never had as much impact on popular consciousness as the original and tends not to be remembered with such general affection. Just because network executives are Philistines does not mean they are wrong about the public taste. Indeed, the opposite may be true.

Roddenberry himself never really understood why 'Star Trek' worked. After all, one of the things he banned from his "perfect" universe in ' Star Trek: the Next Generation' was interpersonal conflict - when it was the arguments between Kirk, Spock, and McCoy, sometimes friendly banter, sometimes serious ethical debate, that made the original so human and appealing.

Other characters also began to emerge. The ground-breaking multi-racial, gender mixed crew of 432 included Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott (James Doohan), Lieutenant Uhuru (Nichelle Nicols), and Lieutenant Sulu (George Takei). However, apart from Spock, it was not a mixed species crew, because that would have put too much pressure on the makeup budget and, in any case, would probably have looked silly.

When, during the second season, Takei went off to shoot 'The Green Berets' with John Wayne, Walter Koenig, as the Russian Ensign Chekhov, stood in for him and then remained as his colleague after his return. Some claim the character was prompted by Russian complaints about their lack of representation given their contribution to Space exploration. Others say it was an attempt to attract younger female viewers, especially since his hairstyle seemed to reference The Monkees. Yet surely the more obvious similarity is with David McCallum's Illya Kuryakin in The Man From U.N.C.L.E.?

Kuryakin should remind us that by 1966, there was nothing particularly original in positive depictions of people of different nations and races on American television. Fans of 'Star Trek' - again, very much in retrospect - tend to exaggerate its significance in the racial politics of the United States in the 1960s. The truth is that it was pushing at an open door by that stage. Desegregation was already happening, the Civil Rights Act was law, the US Military had in fact been integrated for some years, and so there was nothing particularly strange in the idea of a black commissioned officer like Lieutenant Uhura. The contribution of 'Star Trek' was no more and no less than to make the causal mixing of races in the future look inevitable.

The harmonious image of the future to which Star Trek aspired on screen was not reflected behind the scenes. It was a famously unhappy set. Roddenberry was a tough alpha male who liked things done his way. It was perhaps necessary to be like that in the Darwinian environment of American television in the 1960s. Certainly, 'Star Trek' would never have been made if Roddenberry had not been as pushy and aggressive as he was. However, if this won him a lot of fights, it also got him into a lot more that might have been avoided. As a leader, he seems to have been more a Kirk than a Jean-Luc Picard. He fell out with a lot of people unnecessarily and basically cut off his own right hand when he lost his talented Producer, Gene Coon. He ended up sidelined in his own show, nominally still Executive Producer but with everything actually being run by Fred Freiberger in Coon's former post.

There were also feuds among the actors. DeForest Kelly, whom everyone liked, was said to be the only regular who had none. Most of the stories involve William Shatner and complaints, not least from other cast members, about his alleged egotism. The usual version is that Shatner expected to be the star, so he was irritated when other characters began to develop and get more attention - especially when it was clear that Spock was what we would today call the "break out character." In Shatner's defence, there was very much a class system in place within the acting profession at that point, and, having a solid curriculum vitae in film, he was perceived as having taken a demotion in accepting a regular role in a television series. He therefore had a reasonable expectation that the series would be a star vehicle for its leading man - as was the case with most such series at the time.

(It should not be forgotten that he had the reputation of being a serious rising talent before 'Star Trek.' Anyone inclined to doubt that in the wake of T J Hooker might care to check out a 1962 film called 'The Intruder' or 'The Stranger.' Although the words "starring William Shatner" and "directed by Roger Corman" are not usually associated with high quality, it is a very perceptive study of the nature of racism and mob rule that might be strangely topical today.)

The production's internal conflicts were exacerbated by external pressures. The show struggled in the ratings. It did not matter that a few people liked it a lot when insufficient numbers did not like it just enough to tune in every week. Most adults thought science fiction was childish, while the children themselves preferred Westerns, which had more action and less talk about interesting philosophical concepts. The most annoying thing about those network executives is that they were actually right about it being too "cerebral," at least from the only perspective that mattered to them, the ratings.

Legend has it that the show was saved from cancellation at the end of its second season only by a letter writing campaign by fans. While it is true that letters arrived in unprecedented numbers, so that NBC had to abandon its policy of replying to them all, tens and hundreds of thousands mattered little when network ratings were measured in millions and tens of millions. However, it seems that NBC really were genuinely impressed by the quality of the stationery on which many the letters were written. Marketing as a science was still in its infancy, and the networks - and, more importantly, the advertising agencies - were just beginning to look beyond the headline figures to the actual demographics. Good stationery implied that viewers of 'Star Trek' had higher than average disposable incomes. That interested the advertisers.

So the show got its third season, but it was a temporary reprieve. It had entered the vicious circle that has finished off so many good shows: the budgets were cut because the ratings were low, so the quality declined, and as the quality declined the ratings got lower...

This decline may not be so obvious to a casual viewer today, to whom all the 'special effects" and the production values in general now look derisory. To anyone watching every week in 1968, the difference would have been clear. Quite a lot of money had gone into the show in its first two seasons, and much of the production was therefore cutting edge by the standards of the time. That was visibly not the case with the third season when it was first shown. Among other savings, less expensive writers were used. Curiously, these included Gene Coon, writing under a pseudonym, but his guiding hand editing scripts as Producer was sorely missed.

That said, the third season, while it was definitely a confirmation of the Law of Diminishing Returns, does not deserve the scorn with which it is viewed by many hard core Star Trek fans. It includes many of the best remembered episodes, including 'Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,' 'Day of the Dove,' 'The Enterprise Incident,' and 'The Mark of Gideon,' even if the ratio of classics to duds decreased noticeably. One must forget that, although there are couple of dozen episodes of the show that are now acknowledged works of art, and maybe as many again for which people feel great affection out of familiarity, there were in every season others which are practically unwatchable. If there is plenty of evidence to support those who believe 'Star Trek' was a show of superior quality, there is also some to support the those who hold the opposite view.

In the end, that did not matter. Like any other show, it depended entirely on its ratings, and no letter writing campaign was ever going to save it after the third season.

Then came the final act twist. Again like any other show - at a certain level - it was sold into syndication to provide cheap filler. There, and in similar situations in foreign markets, it found an unexpected afterlife. It was perfect repeat fodder. The free-standing structure of the episodes made it easy casual viewing. People may not have bothered to tune in weekly when 'Star Trek' was on the network, but it was a welcome distraction if they happened to find it was on when they were browsing through the channels for something to watch.

It helped that it was bright and visually cheerful. This is a factor programme makers often undervalue. When the box in the corner is struggling to catch and maintain the attention of the people in the room, light and colour are great advantages. It is perhaps very significant that 'Star Trek' grew in popularity at the same time that colour television became the norm. It seems designed specifically to show off the advantages of the new technology - because it was. It could be argued that the person most responsible for the success of 'Star Trek' is not Roddenberry or Coon or Fontana or Shatner or Nimoy but whoever it was who first suggested that the Star Fleet uniforms be made in the three primary colours.

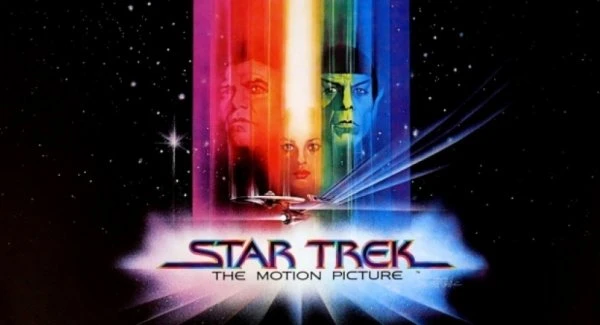

Even so, it might be just another fondly remembered old show had not 'Star Wars' showed the potential of both science fiction and franchise. If Gene Roddenberry fathered Star Trek, it was, indirectly, George Lucas who revived it. A series of 'Star Trek' films soon followed and then Star Trek: The Next Generation, which is what really started the multi-media money making machine that was known at Paramount simply as "The Franchise." As such, only Harry Potter, 'Lord of the Rings,' the Marvel Universe, and 'Star Wars' itself bear comparison, and 'Star Trek' was the only one that started in television. Other television based franchises have since copied its example, but Star Trek remains the biggest and the best - or at least the standard by which all others are judged. There is no sign of that changing.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on July 7th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards, Peter Henshuls and Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.