Star Trek: The Next Generation

1987 - United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards and Peter Henshuls

It is no exaggeration to say that the 'Star Trek' franchise is a significant moment in modern cultural history. Quite apart from its more direct impact on popular consciousness, it changed the way we viewed television. For many years television was, and for the most part still is, an ephemeral medium, like theatre. One watched a show to be entertained for a while and that was it. One might remember a particularly good episode and perhaps talk about it with others, but it had no enduring significance beyond that.

With Star Trek we see the beginning of "cult television," the notion that certain shows can have an influence on some of their viewers that extends beyond the mere watching of the show. The fan enters into a new universe, an imaginary universe that can become as detailed as the one in which we actually live and, in some ways, as realistic. Taken to an extreme, this may be very unhealthy, a pretext for obsession or retreat from real life, but sometimes such shows hold up a mirror to our own universe so that we can see things about it we might not have noticed or considered before. Our imagination thus helps us to understand our reality.

The Star Trek franchise was the first to achieve this completely and remains the most influential. However, it did not set out to do anything like that, nor did it do it immediately. It took about twenty to thirty years, and it was the work of fans as much as producers. The turning point was Star Trek: The Next Generation.

It is usually forgotten, or not really understood by younger fans, that there was nothing particularly special about the "Classic" or original Star Trek. It was just another show. The idea of the "cult" hit did not exist when it was first shown - because it was going to invent it. In the meantime, it lived and died by the ratings, like any other show. The big networks do not care if a few people like a show very much indeed - all that counts is that sufficient numbers like it just enough to watch it regularly every week. Since Star Trek was never that sort of show, it struggled to last three seasons. Indeed, it would not have survived that long but for an unprecedented letter writing campaign by fans. Yet it entered its final season with the assumption it would not last much longer, "a self-fulfilling prophecy" in the words of Nichelle Nicholls, who played Lieutenant Uhura, because it was a pretext for lower budgets and a poor scheduling slot that reduced ratings even more.

So Star Trek was cancelled and that was that - or so it was thought. Dead as a network show, it was duly sold into syndication to provide cheap repeats ...only to discover that there is an afterlife.

The fact that its episodes were free standing, combined with its colour, its clever storytelling, and its strong cast, made it ideal casual viewing. While people had not gone out of their way to watch it regularly when it was scheduled, they found it easy company when they happened to switch on the television and found an episode showing, as one frequently was.

It proved a reliable draw in syndication, and was also repeated frequently in foreign markets, including the UK. As a result, it became something of a familiar friend - and it stuck in the memory because there was nothing else like it. The mythology has it that it was the fans who revived the show, but the brutal commercial truth is that the small numbers who loved it passionately mattered less than the large numbers who had come to like it in what we might today call an ironic sort of way.

There had long been talk of some sort of revival, but such talk is cheap in Hollywood. It was the success of 'Star Wars' that changed everything. There was clearly big money in science fiction after all.

The original cast reprised their roles in a series of films which, after a shaky start, proved very profitable - perhaps a bit too profitable, because it prompted increased salary demands from the stars. Since a follow up television series was already the obvious next move, the economics of the situation suggested that they should hire a new cast to play new characters rather than the more established actors who were now thinking in terms of hit film money.

While this may have made financial sense, it made marketing the show a much tougher proposition. Fans wanted to see more of their old favourites, not a bunch of nobodies trading on their franchise. In any case, "spin off" television shows following successful films as a general rule do not have a good reputation, commercially or critically - there are notable exceptions, but their overall track record is poor. The same is true of belated sequels to shows fondly remembered from years before. Everything suggested that Paramount were simply going to cash in on the name to which they held the legal rights, take their money, and run.

Indeed, it seems that the only people not thinking in those terms were Paramount themselves. They took the project very seriously, bringing in a lot of expensive behind the scenes talent, including the Executive Producer of the original Star Trek, Gene Roddenberry.

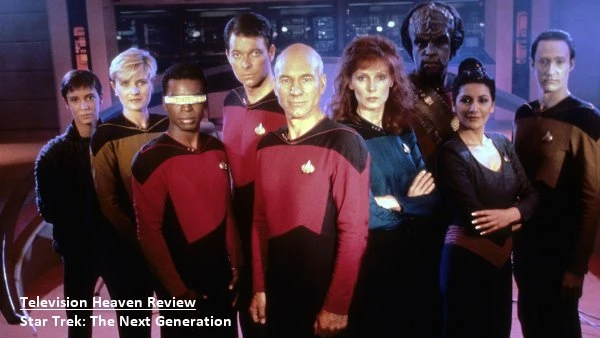

Nevertheless, expectations were low - in the face of disinterest from the big networks, the brave decision was made to sell the brand new show directly into syndication - and the cast list lowered them further. Who were these people? The irony is that it was these relatively obscure actors who turned what could have been another rightly forgotten one season "spin off" or sequel into what is now called simply "The Franchise."

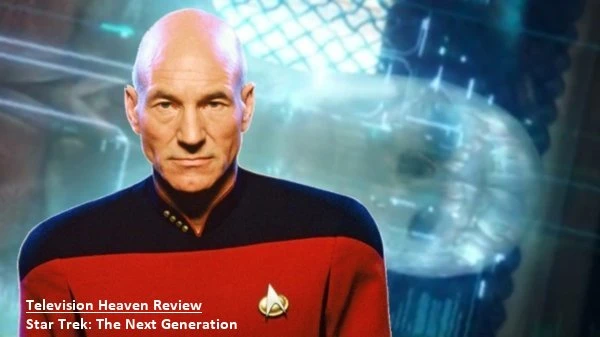

If one decision can be said to have made the difference between the success and failure of Star Trek: The Next Generation it was the casting of Patrick Stewart as Captain Jean-Luc Picard. Stewart was a respected, if not especially distinguished, Shakespearean with a first-class curriculum vitae in prestige British television projects such as Fall of Eagles, I, Claudius, and Smiley's People. Going bald and beginning to look too old for a leading man, he seemed destined for the very long list of fine actors for whom "it" never really happened.

Then one evening, Robert Justman, a Star Trek producer brought on to the new project by Roddenberry, heard Stewart's voice at a literary reading at UCLA and was convinced immediately that the RSC-trained Yorkshireman was ideal to play the Frenchman Picard. Contrary to later claims, Roddenberry himself was less keen. Apparently he wanted Stephen Macht from Cagney and Lacey.

The other person who was reluctant was Stewart. He seems to have had absolutely no notion of the broader cultural significance of Star Trek or its status in the minds of its hardcore fans. A normal working actor, he viewed it as just another job, one that looked unlikely to last long but which would in the meantime give him a serious American television salary which might leave him with something left over for when he went back to less lucrative theatre and British television work. He was therefore reluctant to sign an open ended contract that might commit him to up to six years and it seems it was only his conviction that the new series would only last a season or so that persuaded him.

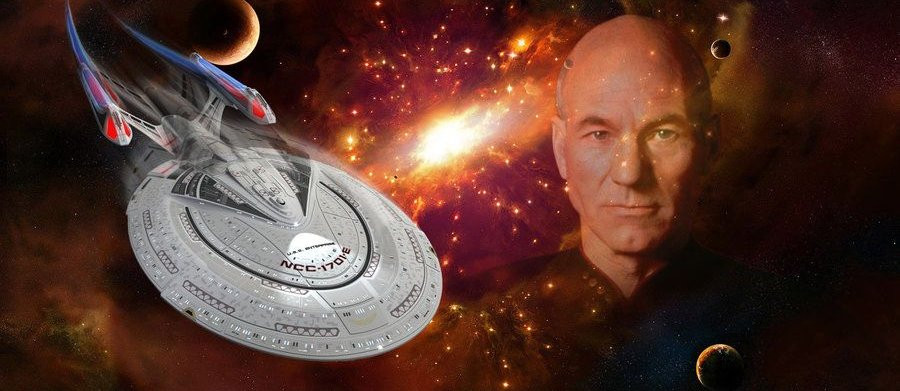

It soon became obvious to both men that casting Stewart was the best thing ever to happen to Stewart's career and to the show. From the moment of his first appearance, his authority over the role of Picard and Picard's authority over the Starship Enterprise are never in doubt. This should be no surprise, because, with the possible exception of Sandhurst, there is nowhere better in the world to learn command presence than the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Picard was a new leader for a new generation. He was the polar opposite of the aggressive, impetuous Captain James Tiberius Kirk who always led from the front in the original Star Trek. Picard was an intellectual, a keen archaeologist who drank Earl Grey tea by the gallon. A diplomat not a warrior, he was cool in a crisis, his emotions, anger as well as fear, under tight restraint. He delegated rather than tried to do everything himself. A father figure, he saw it as part of his role to help his subordinates to develop themselves. As such, he was the epitome of the more collaborative and supportive style of management that was becoming more fashionable in the 1980s and 90s.

There were actually books and articles written along the lines of 'Leadership Lessons from Jean-Luc Picard,' and the fictional character became something of a role model in management theory circles around that time.

Perhaps more surprisingly, he became something of a sex symbol and a chrome domed beacon of hope to balding men everywhere.

By way of balance, the producers gave him a more Kirk-like second-in-command in the form of Commander William Riker. This is a man so overflowing with testosterone that he cannot sit down without throwing his leg over the chair as if he was mounting a horse - a technique known as "the Riker Manoeuvre." Despite the repeated efforts of the writers to convince us otherwise, Riker is not that bright, and a man who would rather spend seven years with his surrogate father than take up the offer of his own command is hardly a natural leader. Nevertheless, as played by Jonathan Frakes, who became an accomplished director working on the show and subsequent films, he is an immensely likeable character, less egotistical than Kirk and less remote than Picard.

Yet the most interesting character in any 'Star Trek' is always the sympathetic outsider who is fascinated by Humanity, and who struggles to understand us and fit in with us. This was Commander Spock in the original Star Trek, Constable Odo in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, the Emergency Medical Hologram in Star Trek: Voyager, and in Star Trek: The Next Generation the android Lieutenant Commander Data, played by Brent Spiner. Data is unfailingly polite, preternaturally calm, slightly pedantic, and ultimately rather poignant in his Pinocchio-like desire to be something he can never be. In an effort to appear more human, he adopted a cat he named Spot - who has no spots - and wrote a poem about him. It was not a very good poem. Indeed, a 2020 "artificial intelligence" could probably write a better one than the 1980s notion of a 24th Century super android. Data is therefore sadly rather dated.

The most high profile name in the initial cast list was probably Denise Crosby, but only because she was Bing Crosby's granddaughter. It shows the status of the project at that stage that she quickly decided it was beneath her and left before the end of the first season. Her character, Chief of Security Tasha Yar, thus became the first regular in any Star Trek series to be killed - rather offhandedly by a jumped up oil slick with some bad special effects. Crosby may well have regretted her decision because her career elsewhere did not exactly flourish and she returned later in several guest slots. Her departure may be doubly regrettable because Yar had potential: several years before Xena: Warrior Princess made them almost mandatory, physically strong female characters were extremely rare. Given a bit more time, Yar might have become the feminist role model that Xena became later.

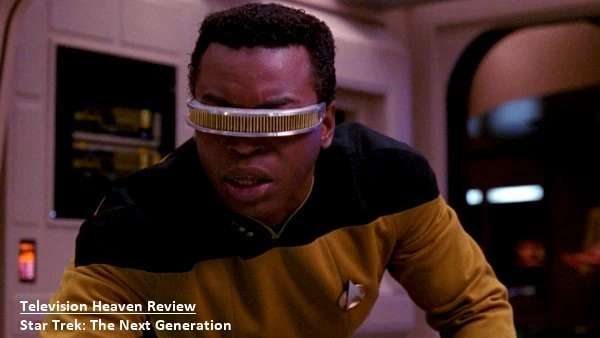

The member of the initial cast previously best known as an actual actor was LeVar Burton, who had played the young Kunta Kinte in Roots. He became Chief Engineer Geordi La Forge, whose principal function was to spout technobabble. Otherwise, there was nothing the writers could do to make him interesting. He was blind, but, since technology gave him a magic visor that enabled him to sort of "see," that really did not make much difference to anything.

Given the ideology openly on display in Star Trek: The Next Generation, one might be forgiven for wondering if the producers were simply going for double "diversity" points with poor Geordi. If so, they were far more successful with another character, putting the representative of a completely alien culture on the command deck - a Klingon, no less.

In the original Star Trek the Klingons were simply generic villains, basically the Communists in the Cold War analogy of the time. With the end of the Cold War in sight, Star Trek: The Next Generation abandoned such simplistic notions and gave the Klingons their own point of view. They became a proud warrior culture - and favourites with a great many fans. They were exemplified by the only Klingon in Star Fleet, Lieutenant Worf.

Michael Dorn, who plays him, might have been a great comedy "straight man." He has a gift for terse one-liners. Worf lives in a state of permanently suppressed fury, or at least exasperation. He goes along with all the happy clappy Federation stuff because he sees it as his duty, and a good Klingon always does his duty, but one suspects he does not really believe in it. As such, he is, ironically, a welcome human touch amid the rather anodyne interactions prompted by Roddenberry's questionable insistence that interpersonal conflict will be a thing of the past by the 24th Century.

This philosophy is summed up by having the "Ship's Counsellor" sitting at the left hand of the Captain while the First Officer sits at the right. Perhaps only in 1980s California could what is in effect the "Ship's Therapist" be elevated to the third most important person on the 'Enterprise.' Although played by the very personable British actress Marina Sirtis, Counsellor Deanna Troi is a thoroughly irritating character. Her big thing is her ability to sense things "empathically," but it proves a useless superpower: she is always either being somehow blocked when it really matters or stating the obvious - "I sense aggression," says Deanna as the 'Enterprise' explodes.

Even more irritating was Acting Ensign Wesley Crusher (Wil Wheaton), a misconceived attempt to attract teenaged male viewers by putting "one of their own" on the command deck. All such attempts ignore the fact that teenaged males are so competitive that they do not think in terms of solidarity, and also that they do not fantasise about being teenaged males: their fantasies are of becoming power figures like Picard or getting all the girls like Riker or both.

Wesley's mother was the Chief Medical Officer, Dr Beverly Crusher, played by Gates McFadden, who was fired at the end of the first season. Apparently she did not get on well with one of the producers, but returned after he left, in part because the other cast members wanted her back.

This leads naturally to one of the biggest reasons for the show's success, its sense of Family, both on screen and off.

While the 'Enterprise' was a warship in the original series, in 'The Next Generation' she became a travelling community, closer to Roddenberry's initial concept of "Wagon Train in Space." Crew members brought their families along with them. As it turned out, this aspect was never really developed and the show became more militarised again after Roddenberry's death in 1991. Anyway, it is significant that none of the regular characters were married or, apart from Beverly and Wesley Crusher, related by blood.

Instead the principals developed into a family of their own, with Picard as Dad, Beverly as occasional Mum, Riker as Dashing Older Brother, Deanna as Sensible Older Sister, and the others as younger siblings who looked up to them.

This on screen chemistry was in part a manifestation of genuine friendships that seem to have developed among the cast members. This is unusual because, while professional actors tend to learn to maintain cordial relations with the people with whom they are working for up to sixteen hours a day, they rarely want to see much of them after that. It is also a big contrast with the original Star Trek, which was a notoriously unhappy set, at least in its television phase.

Another big difference with the original Star Trek is that Star Trek: the Next Generation is very much a product of the revolution in television scripting that began with Hill Street Blues. Drama and humour are blended without looking forced, episodes are still free standing but greater use is made of "cliff-hangers" and story arcs, and multi-strand storytelling takes the place of the focus on a single hero.

Yet the biggest difference of all is as subtle as it is pervasive. In the original Star Trek, we are shown as much of its universe as we need to provide backdrop for the weekly adventures of Kirk and Co, no more. There is not much in the way of texture or detail, and there are often glaring inconsistencies between episodes. In 'The Next Generation' we are presented with a fully realised universe that is as fascinating as some of the stories.

The crucial figure in all this is graphic designer Michael Okuda. His often satirical "Okudagrams," or details of computer displays on the sets, show his attention to detail, but his real influence is as co-author of 'Star Trek: the Next Generation Technical Manual' and 'The Star Trek Encyclopedia,' which act as scholarly reference books about a universe that is entirely fictional. It is perhaps at this point that 'Star Trek' ceases to become a television show and becomes a new cultural phenomenon of its own kind.

Indeed, it becomes a multicultural phenomenon, because alien civilisations, like the Klingon, become as fully realised as the Federation itself - with people actually learning Klingon as a language.

This may have saved the show, because the Federation on its own can become a bit sanctimonious. It was the epitome of everything that Roddenberry and his associates wanted to happen, and they did rather beat the audience over the head with their own politics - basically uncritical 1980s California Left. Some might be attracted by this, others put off, but, either way, it can look very odd now. This is especially true of the show's fanatical interpretation of "The Prime Directive" of non-interference, which Kirk ignored so cheerfully whenever he felt like it. In one episode Picard refuses to rescue an alien race from the destruction of their planet because it would interfere with their culture - and then invites his crew to "honour those lives we cannot save."

Ugh! A show that has so many speeches self-praising Humanity often has little sense of it.

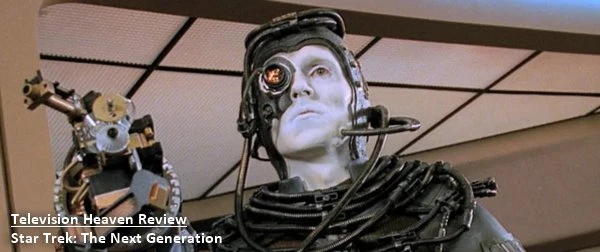

The alien cultures provided a welcome alternative to this hypocrisy. They also challenged Roddenberry's vision of his ideal future with an awkward question the show never really answered: if the Klingons are motivated by honour, the Ferengi by money, the Romulans by power, the Cardassians by service to the State, the Borg by assimilation, and so on, what great principle motivates and unites all the people of the Federation?

It all seems rather aimless. Would we really want to live in Roddenberry's pristine but pointless Utopia? Perhaps 'The Matrix' is right that we actually need the struggles we hate so much. There is no doubt that, when it comes to entertainment, we enjoy our vicarious experience of others overcoming their problems, and others are also the source of most of the problems in our own lives. We therefore identify with the hero who overcomes villains who are the personifications of our own struggles. Whether Roddenberry likes it or not, we are competitive animals.

Partly for this reason, the show took a while to find its way, despite getting off to a strong start with the feature length 'Encounter at Farpoint.' It has been said that a 'Star Trek' series usually takes about three seasons - the whole run of the original - to define its unique identity. This was certainly true of 'The Next Generation.' Many of the early stories are fairly unimaginative and Roddenberry's attitude to interpersonal conflict reduced the opportunities for dramatic tension.

Indeed, most of the show's truly great episodes, such as 'The Inner Light,' 'Chain of Command,' and 'Tapestry,' were made after Roddenberry's tragically early departure left writers free to explore more challenging ideas that might not have accorded with his desire for his universe to be how he wanted it.

These were also the episodes in which Stewart was allowed to explore the man behind the great authority figure and really cut loose with his heavyweight acting skills. They bear rewatching again and again. There are, however, many other episodes, especially in the early seasons, that have not aged as well. In some ways, the original Star Trek has coped better with the passing years.

Nevertheless, Star Trek: the Next Generation deserves credit for reviving the whole genre of science fiction on television almost single handedly, and for achieving the near impossible task of supplanting the original show as the flagship of "The Franchise," even in the eyes of die-hard fans. It remains so to this day - the standard by which all the other series, and televised science fiction in general, is now judged.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 18th, 2020. John Winterson Richards & Peter Henshuls "made it so".