Smiley's People

1982 - United KingdomReview: John Winterson Richards

It seems that there were people who found the BBC's landmark 1979 adaptation of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy insufficiently opaque and incomprehensible. That is the only possible explanation for the Beeb's decision to follow it up with Smiley's People, a sequel so complex that it makes TTSS look like a particularly undemanding episode of Bagpuss.

Both adaptations are based on novels by David Cornwell, aka John le Carre, who served in the Secret Intelligence Service, aka MI6. Together they transformed the whole genre of the spy thriller, which, for almost two decades had been dominated by James Bond and the literally fantastic notion of the "superagent" - a superbly accomplished individual who lived the high life while simultaneously being employed as a spy.

Cornwell's great contribution was to ask "What sort of people really become spies?" People who steal secrets usually do so because they are bribed, blackmailed, or otherwise coerced into it. They are therefore usually people with major weaknesses. Cornwell suggests that what is true of spies is also perhaps, to a lesser extent, true of those who handle them and catch them. They are often people for whom the idea of knowing what others do not know, and having a bit of power that others do not have, is particularly attractive because it helps them mask their own inferiority.

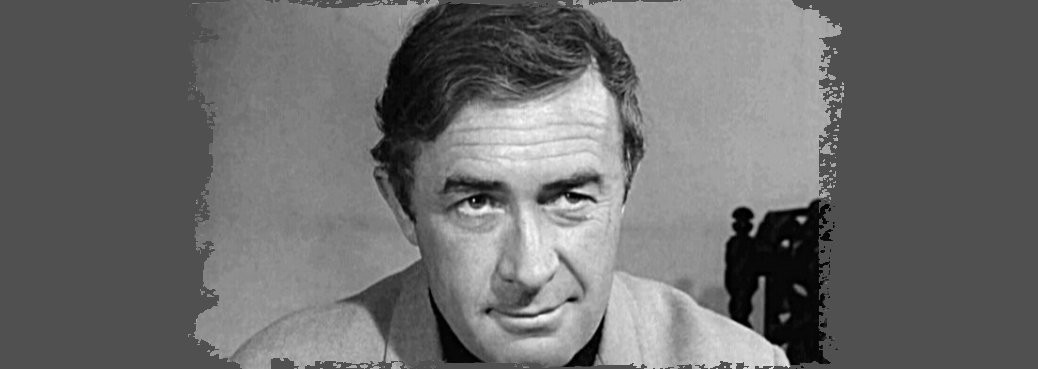

The protagonist - one might even say hero - of Smiley's People is a perfect example. George Smiley is an introverted, cuckolded petty bureaucrat with thick glasses and an eye for detail. He is the complete antithesis of the swashbuckling, womanizing "superagent." He is also totally credible and surprisingly sympathetic.

This is because he is played by Sir Alec Guinness. Indeed, Smiley's People is basically The Alec Guinness Show, a masterclass in acting from start to finish.

It may not be so obvious these days what a risk Guinness was taking. There was a real snobbery until relatively recently about "movie stars" doing television. It was felt that they were endangering their brands by overexposure. When he did TTSS, Guinness was not long off Star Wars . As the most recognisable name in the most successful film of its day, he was arguably the most bankable "movie star" in the world at that point, so, quite apart from the status issue, doing a television series would have been a huge pay cut. (Of course, Guinness had, very shrewdly, held out for a share of the gross on Star Wars, so he could probably afford it.)

It was also a technical risk. Guinness had built his career on subtlety, conveying a lot with a tiny gesture or expression. This is difficult enough on a cinema screen, where the actor is projected to several times his real size and the audience is forced to pay attention to him. It was considered impossible on television.

Remember that the average television screen in the Seventies and Eighties was a lot smaller than its direct equivalent today, and that watching television was more of a communal activity. The whole family might be in the same room, chatting and doing other things while nominally "watching" the small box in the corner. The television therefore had to compete for their attention.

Conventional wisdom at the time was that this was best achieved by being loud and active. Many actors, even good ones, adopted an almost theatrical style when working on television, speaking up and exaggerating their gestures to grab their audience. It does not always age well.

Guinness did the complete opposite. Speaking slowly and quietly, he compelled the watcher to listen carefully in case he missed some important plot point. He succeeded because he was Sir Alec Guinness and also because it was all too easy to lose track completely if one did not concentrate on what was being said.

Where TTSS saw Smiley on the defensive, seeking out a "mole" in his own organisation, Smiley's People had him take the offensive against the KGB. Slowly but surely, he puts the facts together to expose a major human weakness at the very top. He exploits this ruthlessly against "Karla," a high ranking member of the KGB (played by Patrick Stewart, in the pre-Picard days when he tended to be cast as a villain) who previously got the better of him.

Adding to the confusion is the way that some of the characters seem to be completely different people from who they were in TTSS. That great stalwart of Seventies television, Bernard Hepton, enjoys himself particularly in this respect, accent and all.

In the end, Smiley achieves an incredible coup, but it is a bittersweet moment. The briefest of encounters with an unspeaking Karla brings him no satisfaction. Both men are left sharing the understanding that their profession does not come down to patriotism or ideology but to human beings with human frailties. Even the fanatic is vulnerable because his fanaticism is itself a sign that he doubts.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 24th, 2019. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.