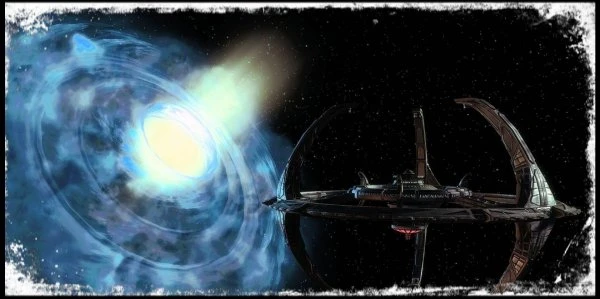

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

1993 - United StatesOriginally intended as a slightly different take on the standard starship-based 'Star Trek' adventures, over seven seasons Star Trek: Deep Space Nine evolved into the darkest and most complex series in "The Franchise" - and possibly the best.

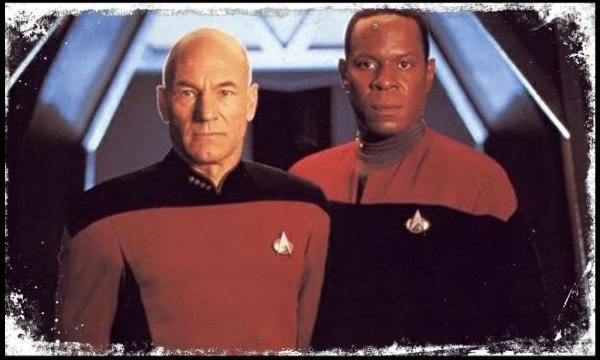

Two years after the death of Gene Roddenberry, the legendary Executive Producer of the original Star Trek and Star Trek: the Next Generation, two able successors, Rick Berman and Michael Piller, thrust the underside of what he saw as his optimistic view of the future defiantly into the spotlight. At the same time that Jean-Luc Picard is at the helm of the 'Enterprise' - he turns up in the first episode - a scratch garrison is having a far less glamorous time of it in a former Cardassian space station near the devastated and politically unstable fringe planet of Bajor.

Remember that Picard's 'Enterprise' is the Flagship of the Federation. It is modern, with all the latest technology that works perfectly. Its crew is a carefully selected and dedicated elite. They get all the interesting missions and are always visiting new places. Picard himself is a well known hero - even if some have legitimate reason to feel negatively about him.

The implication of Star Trek: Deep Space 9 - we will stick to 'DS9' from this point - is that the careers of most Star Fleet personnel were nothing like those of Picard and his command staff. The eponymous space station is old and falling apart. That, added to the practical difficulties of combining different technologies, means that things are always breaking down or in a state of being repaired. Its inhabitants are the flotsam and jetsam of the Final Frontier.

Yet it develops considerable strategic significance at the entrance of an apparently stable "worm hole," a short cut to a distant and largely unexplored quadrant of the Galaxy. Despite its importance, the station - thanks to some superb production design - always retains a definite grungy feel to it. If Star Trek is, in the words of Roddenberry's original pitch, "Wagon Train to the Stars," then 'DS9' is the disreputable cattle town where it stops off.

So nothing is as neat and tidy as it is in the 'Enterprise.' Commerce, which Roddenberry preferred to ignore, becomes a major factor in 'DS9.' This includes alcohol, gambling, and hints of prostitution. In Star Trek: the Next Generation, the "holodeck" is a recreational and educational technology where one might, for example, role play in one's favourite novel or in an historical event. In 'DS9,' it is implied that other uses have been found for "holosuites." They need to be cleaned a lot.

The fully realised universe developed by 'The Next Generation' is made more realistic - and slightly more adult - in 'DS9.' It also addresses other certain realities that Roddenberry wanted banned from his vision of a perfect future, notably politics, religion, and interpersonal conflict. All three end up dominating the life of the principal hero of 'DS9,' despite him being personally an apolitical professional officer, an agnostic, and rather good at resolving disputes.

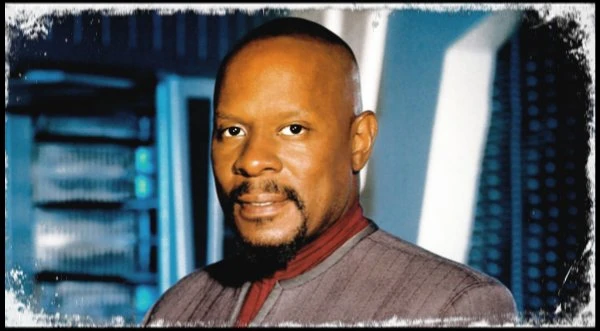

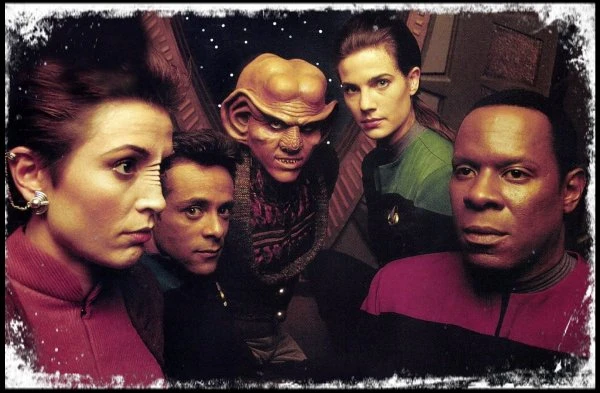

This is Commander, later Captain, Benjamin Sisko, played by Avery Brooks, the senior Federation officer on the station - which remains, however, due to the complicated politics of its situation, under Bajoran civil law. He also finds himself, definitely not by choice, a major figure in the Bajoran religion. His role is therefore more than that of a normal, straightforward commanding officer.

Like Sir Patrick Stewart, who plays Picard, Brooks has a background as a noted Shakespearean. He therefore knows how to project authority, and, although Sisko dislikes Picard, both men share a similar command presence and leadership style. Much was made at the time of Brooks being the first non-white leading man in a 'Star Trek' series, but to be honest, with General Colin Powell already being considered seriously as a potential US President, it really was not that big a deal by 1993. Sisko commands obedience as naturally as Othello - a role with which Brooks was familiar - commanded it from the Venetians.

Family is once again a major theme and, like Picard, Sisko is in effect a Patriarch. Unlike Picard, he is an actual father - to an adolescent son named Jake (Cirroc Lofton) - and was an actual husband: he lost his wife in a battle in which Picard played an important role, hence his antipathy. In the course of the series he becomes romantically involved with a freighter operator named Casidy Yates - the excellent Penny Johnson Jerald, who was later to be so good in 24 - whom he eventually marries.

His more extended family, in true 'Star Trek' tradition, are his command staff and their close connections. If Picard's surrogate family are the equivalent of the Waltons, the model nuclear family most fathers want, Sisko's are the noisy, bickering dysfunctional family most actually get.

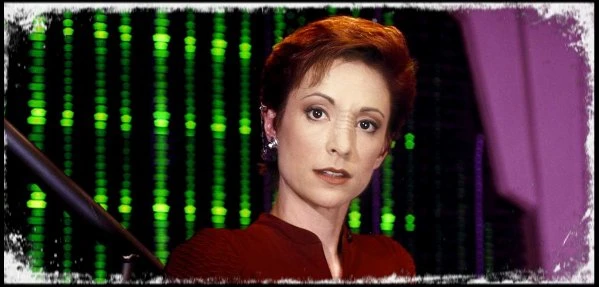

His second in command, Major Kira Nerys, is also the Bajoran liaison officer, so, like Sisko himself, she has divided loyalties. She was active in the Bajoran resistance against the Cardassian occupation of her planet, and implicated in acts that might legitimately be called terrorist. She now has a Militia Commission under the Provisional Government set up after the Cardassian departure from Bajor. Although not a major player herself, she is politically connected.

The original intention of the producers was that this post would be filled by the character of Ro Laren, a Bajoran Star Fleet officer, played by the always watchable Michelle Forbes, who had appeared in Star Trek: The Next Generation. For some reason it is difficult to comprehend, Forbes declined the "spin off" role that had been set up so neatly for her. It was an ill-advised move. Although she has gone on to enjoy an interesting career, she missed out on a signature part that would have defined it.

Kira Nerys, played by Nana Visitor, became a culturally significant characterisation. This was only a few years before women started playing both leaders and leading roles in action adventure drama - Xena, Buffy, and, of course, Kathryn Janeway in Star Trek: Voyager. Television was not quite there yet in 1993, but it was close and Major Kira is an important stepping stone.

She is simultaneously a credible authority figure, an action hero, and a complicated woman. Her sharp exterior hides a brittle vulnerability. She brings with her a lot of emotional baggage from savage fighting against the Cardassians. Despite a brutal early life and her command responsibilities, she retains her femininity. She was a pioneer of a type of character that has since become very common, even obligatory, but has rarely been written or played better.

Less successful is the concept of Dax, a symbiont living in a human host - first Jadzia Dax (Terry Farrell) and then Ezri Dax (Nicole de Boer). Although both were attractive young women, we are asked to believe that Sisko always viewed Dax as an old man because he had been friendly with him as such in a previous host, Curzon Dax. This never convinced and the concept never really worked anyway.

Yet the idea of the symbiont does at least demonstrate the commitment of 'DS9' to aliens who really were alien, not just slight variations on humanoids. A far more interesting example is Constable Odo, a beautifully judged performance by the late Rene Auberjonois.

Odo is a shapeshifter of unknown origin. A being of great integrity, he remains the station's resolutely neutral Constable, or chief of security, through the Cardassian evacuation and all the politicking that follows. Apparently the only one of his species, at least in the beginning, his air of authority masks a very lonely man who is unsure of his identity.

He performs the role that is found in practically every 'Star Trek' series - Spock in the original, Data in 'The Next Generation,' and the Emergency Medical Hologram in 'Voyager' - that of the outsider looking in at Humanity, trying to understand so that he may imitate and fit in ...except in Odo's case, as a shapeshifter, the imitation is literal and physical.

Such is Auberjonois' skill that this imitation, like the best jazz music, is always just that little bit off the beat. Poor Odo is never quite there.

So the romantic relationship he develops with Major Kira seems unlikely, but then it becomes credible because it seems so unlikely. Here are two damaged souls in the immensity of Space together trying to work out who they are behind the facades that their respective positions oblige them to maintain. We begin to hope that, somehow, against all the odds, things will work out for them ...because we know, deep down, that is really not going to happen.

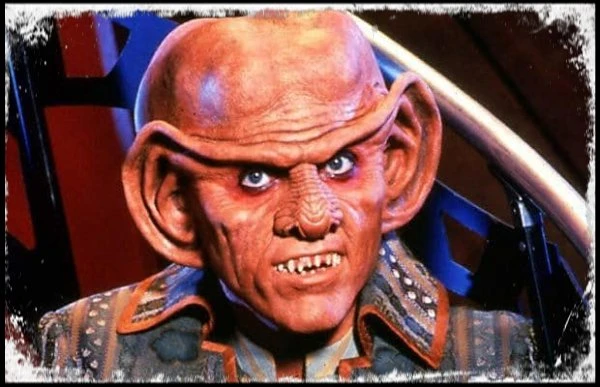

Odo's other close relationship is with his perpetual adversary, Quark, a member of the ruthlessly acquisitive Ferengi race. Quark owns a seedy bar, with a casino and "holosuites" attached, but is open to any potentially profitable enterprise without regard to legality. This puts him on constant collision course with the upright Odo, but, in a strange way the two of them need each other like the symbiont Dax and his host need each other.

Outwardly ugly, and apparently determined to play the villain, Quark, portrayed perfectly by Armin Shimerman, turns out to be unexpectedly sympathetic. For all his quoting of the wonderfully amoral Ferengi "Rules of Acquisition," he has his own integrity, even if it differs from Odo's: Quark is true to himself, to his culture, and, sometimes reluctantly, to those he has come to consider as his friends. Where other characters spout high principles and end up having to live with unpleasant moral compromises, Quark is selfish and practical but capable of acts of generosity that mean far more coming from him.

The station's Medical Officer, Dr Julian Bashir, played by Alexander Siddig, is another character about whom the viewer's feelings change. Initially he is brash and insensitive, apparently a brilliant young man who does not mind who knows it. Yet there is a secret to this brilliance, and beneath his arrogant exterior, Julian is, like many who wash up at the station, uncertain and alone. In many ways, 'DS9' is the story of Dr Bashir growing up.

He strikes up an unlikely friendship with Chief Miles O'Brien - but then in friendship, as in romantic love, opposites often attract. O'Brien is a mature family man and a senior Non Commissioned Officer, both the character and Colm Meaney, the actor who plays him, having risen through the ranks together. He appeared first in Star Trek: the Next Generation as an anonymous character, little more than an "extra." Eventually he was given a name, together with a job title, Transporter Chief on the 'Enterprise.' From there he was promoted to a frequent recurring role in 'The Next Generation' with his own storylines. Finally, he was promoted sideways to full series regular in the "spin off," as the man who is fighting a never-ending battle to stop the station falling apart. While all this was going on, Meaney also became a familiar face in British, American, and Irish feature films, a very busy man.

Later, as the storylines became more military, the cast was joined by another veteran of 'The Next Generation,' this time one who had been a series regular of that show too - the popular Klingon Worf, played by Michael Dorn. We were asked to believe Worf fell in love with Jadzia Dax, but his more convincing love affair was with the small fast attack starship 'Defiant,' which was introduced to make the show less static.

That was always a problem for the writers. Starships go places. Space stations do not - or at least, if they do, not far and very slowly. Interesting people must come to them, rather than vice versa. It was mainly in dealing with that problem that 'DS9' relied more on recurring guest characters than any other show in the franchise. Some became so frequent that they seemed like regulars.

James Darren, fondly remembered from Time Tunnel, is a delight as "Vic Fontaine," a "holosuite" programme in the form of a Sinatra-esque lounge singer which takes on a life of its own - yes, it makes no sense at all in a science fiction show, but the Rat Pack vibe is still cool. Majel Barrett, Roddenberry's widow and "The First Lady of Star Trek," turns up in her 'Next Generation' role of Lwaxana Troi. Wallace Shawn of 'The Princess Bride' fame is perfectly cast as Grand Nagus Zek, the ruler of the Ferengi - anyone else in the role would have been inconceivable. Louise Fletcher, the legendary Nurse Ratched, is a self-serving Bajoran religious leader. Marc Alaimo is Gul Dukat, the last Cardassian Prefect of Bajor and a man who has trouble letting go.

Yet the most memorable of many memorable recurring characters is Elim Garak, played by the superb Andy Robinson who was so convincing as the villain in 'Dirty Harry' - indeed, perhaps too convincing because such was the impact he made on the public mind that he got very little work for years after that film and his big comeback, in 'DS9,' was under heavy make up and under the name Andrew J Robinson.

From a viewer's point of view, it was worth the wait. Garak is one of the great television characters of all time. The only Cardassian left on the station after their withdrawal, he keeps claiming that he is "just a tailor" - but since he is open about lying, no one believes him. He gives the impression that he has previously been involved in intelligence work, but could this be another of his deceits? No, it turns out that he is more deeply involved than anyone might have imagined. More cheerfully amoral even than Quark, he is a trained and remorseless killer with a gift for high level intrigue. For all that, he retains a certain charm, and there is a strange honesty in his making it very clear that he should not be trusted.

Political intrigue is a major theme in 'DS9.' We see it in high level diplomacy between the species but also within species, including the Bajorans, the Cardassians, the Romulans, and the Klingons. Rather shockingly, we even see it within the Federation.

It turns out that there is a conspiracy, known as Section 31, at the very heart of the Federation. More than that, it is suggested that it is the conspiracy that keeps the whole thing going, protecting it from itself by doing all the dirty work necessary for survival that the Federation's high minded ideals prohibit.

This runs completely contrary to Roddenberry's vision. Yet, even if one does not accept the conspiracy's view of itself, it raises awkward questions. It is implied that the Federation is a democracy, but Roddenberry's dislike of conflict means that there is no sign of the clash of ideas that is essential to any healthy democracy. Does everyone in the Federation think the same? If so, it seems a creepy place. If not, where is the dissent?

There are hints of it in 'DS9.' In one episode, Worf, of all people, is attracted by a group who want to return the Federation to its original values. Yet it is never made entirely clear what is meant by those values - or whether Section 31 is their ultimate guardian or working against them to promote some other values. One way or the other, there is a serpent in Roddenberry's paradise.

Talking of which, Roddenberry, although apparently not an atheist as such, was also adamant that religion would have no part in his ideal future, nor would any form of mysticism. Yet organised religion and mysticism are major themes in 'DS9,' and play a driving role in the plot.

More than that, we have a sympathetic figure, Major Kira, with a sincere religious faith which is very important to her. She is well aware of the scientific explanations for the phenomena on which her Bajoran religion is based, and of the corruption of its religious hierarchy, but she remains a believer. She is a good example of Stephen Jay Gould's concept of "non overlapping magisteria," hints of which can be seen in a letter of Galileo over three hundred years before in which he says faith and science are different types of understanding (unhappily, Galileo, a devout man, did not follow his own advice and famously later got into trouble when he attempted to reconcile the two).

In running into this minefield, the show dodges the question of the existence of the Supreme Being by pointing out the possibility of Higher Intelligence which is not necessarily Omniscient, Omnipresent, and Omnipotent. Thus, the Bajoran "Prophets" and the "Founders" are objects of religious reverence but they are not equated with God.

This is very diplomatic on the part of the producers. Theists should not be offended because it is not blasphemous to portray an intermediate Higher Intelligence rather than the Supreme Being, while at the same time atheists should not be offended because such Higher Intelligence is by no means inconsistent with a purely naturalistic view of the Universe. After all, it was a noted atheist who pointed out that, given the sheer scale of the Universe, it is by no means impossible that beings of much greater intelligence than us might have evolved, while another pointed out that the powers of such beings might appear magical, even "divine," to more primitive intelligence. Of course, this does not mean that such beings do exist - none of the arguments of necessity that can be used for the existence of the Supreme Being apply to them - only that there is nothing to say that they do not. They fall victim to Ockham's Razor, because they are unnecessary, but that does not mean they cannot exist, because most things that do exist are also unnecessary.

These are some pretty big concepts for an action adventure show, and if 'DS9' obviously does not go into them in great depth it is still to its credit that it prompts the questions, even if it is not its job to provide the answers. In this it is superior to the previous two series of 'Star Trek,' which liked to raise clever metaphysical and ethical questions but which kept some of the most interesting areas of discussion strictly off limits.

This willingness of 'DS9' to go where no 'Star Trek' has gone before applies to its whole structure. Episodes of the original Star Trek were all free standing. So are most episodes of 'The Next Generation,' except greater use is made of "cliff hangers" and there are increasingly more frequent references back to earlier episodes. In 'DS9,' everything changes with long preplanned story and character arcs, some lasting several seasons.

This culminates in the "Dominion War" arc, in effect an historical epic, except set in an entirely fictional future, complete with grand strategy, high diplomacy, and fairly spectacular pitched battles. The last, needless to say, are CGI and not particularly realistic, but they are proof of the scope of the producers' ambition.

Where Star Trek: the Next Generation developed an ever more detailed Universe as background, 'DS9' moves it around. In the end, as in all good drama, characters are not the same as they were in the beginning - and neither is the Galaxy.

In an attempt to tack on an ending of which Roddenberry might have approved, the Federation emerges victorious as the sole superpower in the Quadrant. This smacks of the triumphalism that lasted well into the 1990s after America's victory in the Cold War when the talk was of "the end of history" but it does not ring true in the show any more than it did in real life back then.

For the lesson of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is that nothing is certain, there is no such thing as historical inevitably, and the unexpected always happens. After all, it was the opening of the "worm hole," seen as a great opportunity at the time, that led directly to a devastating war. What else is out there waiting to happen?

Ultimately, 'DS9' is all about the loss of innocence, the same innocence that gave the original Star Trek and STTNG much of their charm. Its defining episode, and arguably its best, 'In the Pale Moonlight,' ends with a good and noble man saying something one could never imagine coming from Picard or even Kirk. It is a pivotal moment in science fiction.

By a curious coincidence - such things often happen, as if an idea is in the air at a certain point - 'DS9' ran almost simultaneously with Babylon 5, which was also set on a space station and with which it had many similarities, especially its engagement with politics, religion, and secret conspiracies. Indeed, in many ways, the two had more in common with each other than 'DS9' did with the previous versions of 'Star Trek.'

Although the 'Star Trek' franchise itself then went back to its roots with the more traditional format of Star Trek: Voyager, the influence of 'DS9' on science fiction in general has been greater than that of any of the 'Star Trek' shows that followed it. One can see its more cautious, even cynical view clearly in, for example, Firefly, the reboot of Battlestar Galactica, and The Expanse.

It was on 'DS9' that television science fiction, like Julian Bashir, really grew up.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 19th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards and Peter Henshuls for Television Heaven.