Fall of Eagles

1974 - United KingdomReview by John Winterson Richards

Bird lovers need not worry. The eagles that do the falling in Fall of Eagles are the three Imperial Houses of Eastern and Central Europe during the First World War, the Romanov Tsars of Russia, the Hohenzollern Kaisers of Germany, and the Habsburg Emperors of Austria and Hungary.

All three had eagles as their heraldic symbols - which rather suggests a lack of originality in their thinking. That is indeed the basic thesis of the BBC's series of thirteen freestanding but related dramas from 1974. The rulers of all three Empires are portrayed as inward looking, lacking in vision, and obsessed with each other rather than trying to understand the immense changes that were occurring in the world around them.

The script keeps hitting us over the head with this idea. There is, of course, a great deal of truth to it, but it is not long before it begins to seem rather simplistic. It overlooks the fact that, for all their limited education and experience, these reactionary aristocrats presided over rapid modernisation of their respective Empires.

The series opens in 1853, at which point life for many in the three Empires was not that much changed from the time of the Napoleonic Wars, which were then still very much within living memory. It ends in 1918, in what is recognizably the modern world in which many people today were brought up, the world of electricity, cars, aeroplanes, and telephones. For most of the time in between, the Great Powers of Europe were at peace with each other, and on the whole their subjects enjoyed a massive increase in their material prosperity and personal freedoms, even if these benefits were not spread universally or evenly. All this is difficult to convey with limited television budgets.

So most of the focus is necessarily on the domestic dramas within and between the three Imperial Families. There is certainly enough there to keep a "soap opera" going for some time: the misjudged arranged marriages of the Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria and the future Kaiser Friedrich of Germany; the difficult relationship between the future Kaiser Wilhelm II and his parents; the consequences of the suicide of one heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary and the assassination of another; and the sad love story of the shy Czar Nicholas II.

There is indeed plenty of good human drama here, and it is well presented by a grand cast. Yet, in the end, it seems a bit unfair of the whole production, having made the deliberate choice - or been forced by budgetary constraints - to concentrate on the family aspects of the history of these three Imperial Houses, to imply then that the Imperial Houses were themselves obsessed by the subject and that nothing else was of much significance to them. That was far from the case. These were families who always had a strong sense of the nature of power.

John Elliot, who had co-written A For Andromeda with Fred Hoyle, put together a crack team of writers, including Jack Pulman and Troy Kennedy Martin - who were destined to go on to cover themselves in glory with I, Claudius and Edge of Darkness respectively - from the extraordinarily deep pool of talent Britain had at the time.

It is fair to say that some of these writers, including Kennedy Martin and the militant Socialist Trevor Griffiths, had strong connections with the political Left, and this certainly comes across in the general perspective of the production. This is particularly obvious in the strangely sympathetic portrayal of Vladimir Lenin (Patrick Stewart), which ultimately becomes almost hagiographic. His thread ends with him being received rapturously by an apparently spontaneous demonstration on his return to Russia from exile (the actual event was in fact carefully arranged by his organisation).

A better ending to the Russian thread from both the dramatic and historical point of view would have been to show the well-meaning but ineffective Czar Nicholas II murdered brutally in a basement by Lenin's followers - along with his wife, children, servants, and pet dog. That was the real end of the Romanov Dynasty.

To miss such an obvious scene does rather confirm certain clichés and conspiracy theories about the BBC in the 1970s.

Yet if the intention was to portray the various aristocrats as a bunch of self-absorbed idiots, it was undermined by the excellence of the cast most of whom were incapable of providing anything but three dimensional characterisations.

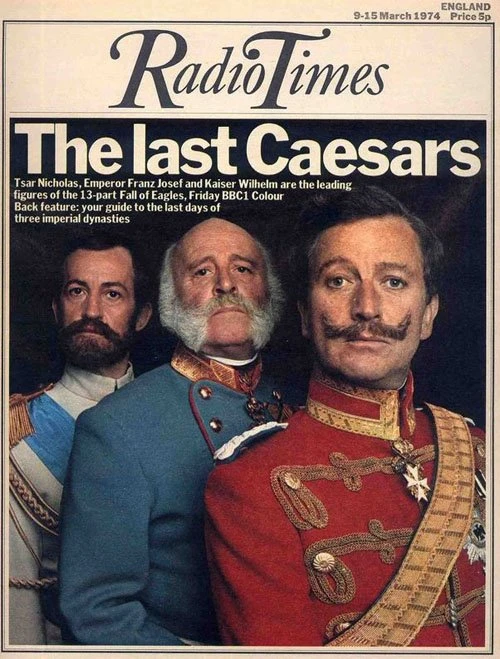

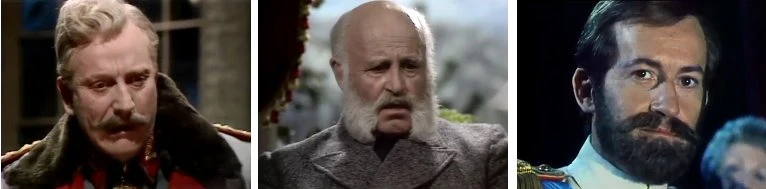

Accomplished veteran Laurence Naismith, 'The Amazing Mr Blunden,' was practically born to play Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph, who seems to be hiding a deep inner vulnerability behind a facade of strict formalism. However, the other two Emperors at the start of the Great War were played by actors cast very much against type - both to great success. Barry Foster, a million miles from Van der Valk, manages to evoke a surprising sympathy for the bumptious Kaiser Wilhelm II, suggesting a man who became a bully because he was bullied.

Best of all is Charles Kay, an actor who has made a fine career out of playing arrogant authority figures - his partnership with Ian McNeice as Harcourt and Pendleton in Kennedy Martin's Edge of Darkness should have got its own spin off series. Here he goes behind the scenes of one such character to paint a moving intimate portrait of the Last Tsar, Nicholas II, a sensitive man who is out of his depth and knows it: secretly terrified of being found out, he resorts to living an extended but ultimately unsuccessful impersonation of his alpha male father.

German film star Curd Jürgens was brought in to play to play the biggest alpha male of all at the time, Otto von Bismarck. He gives a suitably commanding performance, conveying both Bismarck's domineering personality and his emotional nature. Here is yet another great historical figure who uses an outward display of power to mask fears of inner weakness, except Bismarck had the intellect and the strength of character to carry it off and become what he pretended to be.

The supporting cast reads like a roll call of a particularly glorious time for British acting talent, including Gemma Jones, Peter Vaughan, Charles Gray, Marius Goring, Michael Bryant, Esmond Knight, T P McKenna, Maurice Denham, Gayle Hunnicutt, Geoffrey Chater, Diane Keen, Frank Thornton, Freddie Jones, Bruce Purchase, Isla Blair, Vernon Dobtcheff, Kenneth Colley, David Swift, Frank Middlemass, Nigel Stock, Andrew Keir, Hugh Burden, Colin Baker, Jan Francis, Michael Kitchen, Michael Bates, Paul Eddington, Michael Gough, Colin Jeavons, Tom Conti, and a young John Rhys-Davies. Those were the days.

The whole thing is drawn together with a narration in the world weary but oddly reassuring tone of Michael Hordern.

Having splashed out on the cast and costumes, the BBC did not have so much to spend on location and sets. As a result, production values vary between episodes. There are a lot of drawing room scenes, and one episode leaves the impression of being shot largely in a greenhouse and another on the deck of a ship in a studio.

This variation in production values is itself a reflection of a variation in the overall quality of individual episodes. This is to be expected, given that the basic concept was to have a series of separate but linked playlets, written by different people and without a regular cast, even if some characters do turn up in several episodes.

Curiously, some of the best episodes are those which focus on relatively obscure passages of history and which therefore did not get the biggest budgets. The ship in the studio episode, for example, was a great actors' piece about how the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs was outmaneuvered by the Austro-Hungarians over Bosnia-Herzegovina, a comic sideshow that was to have tragic consequences later. It prompts the question whether the Great War, and the consequent destruction of all three Imperial Houses, might have been avoided if Russia had felt less humiliated. It also prompts the question "Why was Peter Vaughan never knighted?" What a superb actor he was.

The undoubted success of Fall of Eagles began a memorable run of quality historical dramas for the BBC that reached its zenith with I,Claudius and ended with The Cleopatras. The Beeb still basks in the glory of the image it built up at that time, and it is often forgotten that, subject to some notable exceptions like Elizabeth R and Henry VIII until Fall of Eagles, serious historical drama was a genre dominated in the UK by the free spending ITV with the likes of The Caesars and Napoleon and Love. So Fall of Eagles is itself an important part of the BBC's own history.

It is also, from personal experience, highly recommended to anyone doing this period at A-level.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 13th, 2020. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.