The Name of the Rose

2019 - ItalyReview: John Winterson Richards

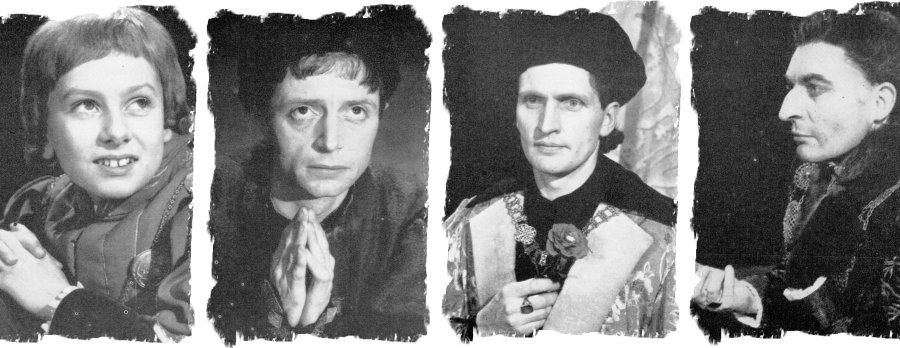

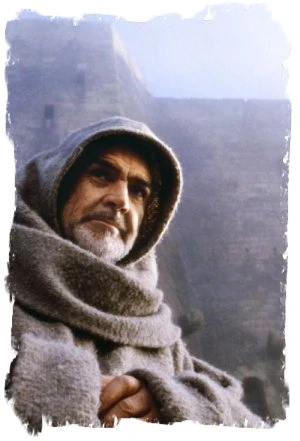

It is surprising that Umberto Eco is said to have disliked Jean-Jacques Annaud's feature film version of his novel 'The Name of the Rose,' which starred Sean Connery, Christian Slater, F Murray Abraham, Michael Lonsdale, and Ron Perlman. After all, Eco probably owes more sales of his books to that film than to anything else.

One can only speculate that he might have received a lot of hate mail from readers who bought his books having seen the film and were therefore expecting Mediaeval detective stories of "Murder at the Abbey" on the lines of Ellis Peters/Edith Pargeter's 'Cadfael' - only to find dense postmodern texts, heavy with many layers of symbolism, exploring the impossibility of determining objective truth through subjective perceptions.

Eco, it should never be forgotten, was a distinguished Professor of Semiotics, the study of signification and meaning - nice work if you can get it...

Perhaps he ought to have been cheered by the fact that Annaud's vision of the book is so different from his own is itself evidence in favour of the theory on which he built his academic career, that any text must be considered "open" and can therefore be interpreted in different ways.

On that principle, there is plenty of scope for different interpretations of a work, especially one as complex as 'The Name of the Rose.' In particular, there was, as with most adaptations, much in the novel that the film left out. At the same time, there is also much in the film that is not found in the novel - especially, of course, in its visual style. Annaud had adopted a sort of High Gothic aesthetic - in the melodramatic sense rather than the architectural - with muted colours, not unlike the classic black and white Hollywood horror films of the 1930s or German Expressionism.

At the same time, the supporting characters were turned into grotesques and there was a heightened sense of claustrophobia in the mountain Abbey. This was very effective on its own terms, but it altered the tone of the story in ways that were not implied in the novel.

So, although it seemed a strange use of resources to remake such a respected film for television, it was not an unjustifiable decision. It may also have been hoped that a television series might have given the writers the space to expand some of the themes and subtexts of the novel in a way that time constraints made impossible in a feature film. Could we at last see an adaptation that Eco, who died not long before production began, might actually have liked?

Even if that seems too much to ask, Eco fans did at least have some reason to hope that the television version might be closer to the novel, or some of their individual readings of the novel, than the film.

They were destined to be disappointed. The television version is, if anything, even further from the book than the film and it is a fair bet that Eco would hate it. Would he be right to do so? After all, he disliked the film, which a lot of people, including this reviewer, liked a lot. In any case, taste is subjective - or, as Eco the Professor of Semiotics would be the first to point out, the work is open to multiple interpretations.

Sadly, the television The Name of the Rose is at best an honourable failure judged even on its own terms. This is doubly a pity because there is much about it that deserves credit. First of all, it ought to be praised for going its own way in terms of visual style. This is not to say that it is necessarily superior to the film in this respect, but having the courage to be different was a good beginning.

So in place of the film's dark, confined aesthetic, the "miniseries" opens up the story both literally and visually, and gives us a lot of beautiful location work. Most of the locations are in Central Italy, further South than the Alpine setting implied in the novel and the film, but all the more appealing to the eye for that. It is no surprise that the Italian state broadcaster RAI co-produced: they are the acknowledged masters of making Italy look even more gorgeous, if such a thing is possible.

There is more interior light and colour, and the characters get outside more. Indeed, they are outside the Abbey more than in the book, and more than would have been likely under monastic rule. Is anyone complaining? No. It is a good excuse to see more of the Italian landscape. Although it is set in winter, it seems to be a mild winter with bright clear skies.

That everything seems so cheerful actually heightens the impact of the horrible events that occur against this background. So does the fact that the monks and other characters seem more like normal people than they do in the film.

The "miniseries" also begins with a commendable attempt to put the events in the Abbey in the political and theological context to which the novel alludes, and which the film did not have the time to address properly, even if it had wanted. That fine French actor, Tcheky Karyo, best known to British television viewers as Julien Baptiste from The Missing and Baptiste, was brought in as Pope XXII.

It was therefore particularly annoying, after this encouraging start, that the production seems to have lost interest in this aspect very quickly, and Karyo and the equally compelling Sebastian Koch, as a Baron representing the secular State, are there for little more than cameos.

Even more annoying is a character who does not appear in the novel, the daughter of the dead leader of an heretical sect, who just happens to be some sort of post-Xena female super-warrior with the power to defeat multiple trained and fully armoured Papal knights. There can be no more grating example of the committee mentality of modern co-production. Someone obviously worried that a show largely about celibate men was unlikely to appeal to female demographics. Then someone else probably piped up that increased representation of women should take the form of a positive, assertive role model.

The whole story is unbalanced - tension is gone when we know Mediaeval Xena is there to save the day if needed - and all historical credibility goes out of the window.

The rest of the cast is worthy of the book and holds well in comparison even with the talented big name actors in the film. John Turturro is no closer to how Eco saw the novel's hero, William of Baskerville, than Sean Connery - it is quite clear from the book that, as his name suggests, he was basically intended to be Sherlock Holmes in a cowl - but Turturro is historically more credible, because he looks and talks like an authentic Franciscan monk of the hardline "Spiritual" faction. Indeed, it is a great performance in its own right, and Turturro the co-writer and co-producer should have put more emphasis on Turturro the actor.

By contrast, Rupert Everett is reduced to playing a pantomime villain as historical Inquisitor Bernard Gui. Historians are beginning to take a more nuanced view of the Mediaeval Inquisition, and Gui seems to have been relatively "liberal." However, the novel makes him a stereotype, F Murray Abraham makes him look even worse in the film, and Everett takes him right over the top. It is a missed opportunity: it would have been interesting to delve into the psychology of the historical Gui.

Michael Emerson, so good in Person of Interest, shows a touching vulnerability as the out of his depth Abbot trying desperately to hold on to the illusion of his authority. In the end he is rather thrown away, another missed opportunity because he is a character of whom we would like to have seen and learned more.

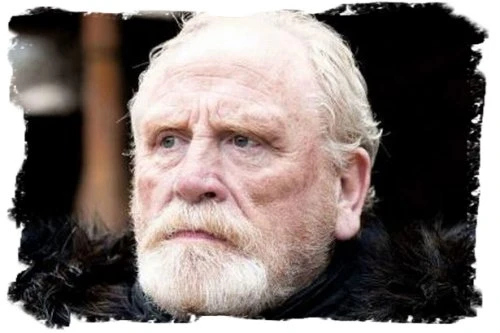

Best of all is James Cosmo as the blind keeper of the secrets of the hidden library. Blessed with an imposing physical presence, Cosmo has forged an outstanding career in "tough guy" roles, so it is easy to overlook what an intelligent and versatile actor he can be when given the material. Where the film telegraphed the true nature of the character from the start, the "miniseries" maintains a certain ambiguity: it is clear that this person is going to be important but a viewer who has not read the book or seen the film might find himself hard put to guess which side of the fence he is going to fall.

That there are these positive elements to the production only makes it more depressing that it fell short. There could have been something special here but the departures from its source material ensured that the film remains the definitive version to date.

So, once again, a lot of time and money and effort was wasted on the false security of an unwanted retread of an established classic when it would actually have been a better commercial decision to invest in new material which might turn out to be a future classic.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on May 6th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.