Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years

1981 - United KingdomHardy is only one of an outstanding cast

Winston Churchill the Wilderness Years is reviewed by John Winterson Richards

Even if he had not saved Western Civilisation in 1940-41, Winston Churchill would have been remembered as a man who led a remarkable life. It Is quite intimidating how he seems to have done everything.

Any decade of his adulthood could furnish enough story for a film or a television series, as he could fit more into ten years than most people do in a whole lifetime. In his youth, he was in effect a real-life John Buchan hero, winning a polo championship with a last minute goal, volunteering for five campaigns, taking part in the last great British cavalry charge at the Battle of Omdurman, and escaping from the Boers after being captured in an armoured train ambush which might have won him the VC had he not been there as a war correspondent. As a young politician, he opened the first Labour Exchanges, converted the Royal Navy from coal to oil, oversaw the development of the first tanks, founded the Royal Air Force as a separate organisation, and gave us much of the map of the Middle East we have today. Even his eightieth year he won the Nobel Prize for Literature and had his paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy - while still serving as Prime Minister.

We had a somewhat better class of politicians in those days.

Yet it could be argued that Churchill was at his greatest not in 1940-41 but during the worst decade of his life, including most of the 1930s, when he was out of office with little prospect of ever returning to it. Failure after failure convinced him that his career was over and he was driven to the lowest depths of despair. He could see the dangers facing the World, especially from the new National Socialist regime in Germany, but was helpless to do anything about them. His warnings were ignored. He was truly a secular prophet almost alone in the wilderness.

Still he continued to warn, and it was during this period that he developed the strength of character and resilience, not always evident in previous years, that were to prove decisive in 1940-41. It was these "Wilderness Years" that subjected him to the most severe test - and made him stronger.

This is the stuff of drama and in 1981 Southern Television spent over three million pounds - a huge sum in those days - on an eight-episode prestige project for the ITV network, Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years. One can see where the money went. Although there were no big international stars, the cream of a talented generation of British actors were rounded up. There was a strong commitment to filming on location, including Churchill's birthplace at Blenheim Palace and his family home at Chartwell in Kent. An impressive set of the House of Commons was positively packed with extras for the big Parliamentary showdowns. Composer Carl Davis, at the height of his powers, provided a rousing theme.

There was a strong commitment to historical accuracy in every department - locations, sets, dressing, props, costumes, and, above all the script. The last puts most recent historical drama to shame. It strengthens the emotional experience of the production when we are assured that what we are seeing and hearing really happened. As often as not these are the actual words that were spoken by real people. There are necessarily some changes, and many omissions, in the name of dramatic convenience, but for the most part what we are given in Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years is authentic in every detail - right down to nice touches like the use of Sarah Churchill's family nickname "Mule" and the Speaker not wearing a wig in a Commons scene because there was a Deputy in the Chair that day.

This accuracy is not surprising given that Churchill's Official Biographer, Sir Martin Gilbert was closely involved in the production as Historical Adviser. The fifth volume of the Official Biography, 'Prophet of Truth,' which deals with the Wilderness Years, was published shortly before the production began, and a special abridged edition of 'Prophet of Truth,' titled 'The Wilderness Years,' was brought out to tie in with the show, which therefore represents a certain point of view.

Sir Martin was a particularly meticulous historian, but, like all who study any controversial topic closely, he had strong opinions of his own on many points. The show, like his books, represent his Churchill-centric and pro-Churchill view of British politics in the 1930s.

Any show is also a product of the time in which it was made. For many years, the prevailing narrative has been how Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain, and the "Appeasers" contributed to the causes of the Second World War by ignoring Churchill's warnings about Hitler. This is known as the "Guilty Men" theory after an influential wartime booklet written by three journalists who happened to be employed by Churchill's close friend Lord Beaverbrook.

This narrative is the spine of the plot in Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years. It was almost unquestioned orthodoxy in 1981 when the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, modelled herself deliberately on Churchill, and the Leader of the Opposition, at that point generally considered to be the likely next Prime Minister, was Michael Foot, one of the authors of the original 'Guilty Men' booklet.

Historiography has moved on since then and historians tend to take a more nuanced view of a lot of things. In particular, it is now generally accepted that, politically and militarily, Neville Chamberlain could not have taken Britain to war over Czechoslovakia in 1938 even if he had wanted - which, as the script conveys accurately, he definitely did not. British public opinion was overwhelmingly for peace after the huge losses of the Great War, and even Chamberlain's modest and belated attempts at rearmament were met by opposition, not least from the Labour Party, including the young Michael Foot. Also not mentioned in the script is the fact that one of the most diligent parers of military expenditure in the 1920s was the Chancellor of the Exchequer in Baldwin's previous Ministry - Winston Churchill.

There are many other omissions in the script - necessarily so, because, even as it is, a great deal of exposition is required. The casual viewer never gets a proper sense of Churchill's strange position in British politics at the time: he was a high ranking and experienced statesman but something of a gadfly, widely regarded as both very clever and very unreliable. Beyond a few close friends and casual allies, from both extremes of the Conservative Party, on different issues, he had no real following of his own, and so was not the major player that hindsight, and the script, assume he must have been. The real bogeyman of the British Establishment at the time was not Churchill but his old friend and mentor, David Lloyd George, who was hoping for a comeback as Prime Minister as late as 1940. It is significant that Lloyd George is barely mentioned, and never appears, in Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years.

The script nevertheless deserves credit for its brutal honesty about some of Churchill's many imperfections. He often chose his battlegrounds poorly, going against the tide of history on India (even if he was proved right about the massacres that would result), getting obsessed with irrelevant details of an inquiry into alleged tampering with a submission of evidence to Parliament, and defending Edward VIII in the Abdication Crisis, which did much to damage his credibility. He was a poor businessman. He was perpetually short of cash, not least because this did nothing to alter the spending habits he always felt appropriate to the grandson of a Duke. This, combined with a taste for gambling, led him to some badly judged investment decisions. On at least three occasions he was bailed out by the generosity of several very wealthy friends. He also benefited politically from a close association with several media moguls, including Beaverbrook, Lord Camrose of 'The Telegraph,' and Brendan Bracken that would attract comment today. He was a caring father but his alternating between overindulgence and Victorian strictness may have contributed to the problems exhibited by at least two of his children.

For all these faults, Churchill was still a very great man and Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years rightly reminds us why. The point is that we should not expect our heroes to be perfect. Churchill was certainly not perfect but is no less a hero for that.

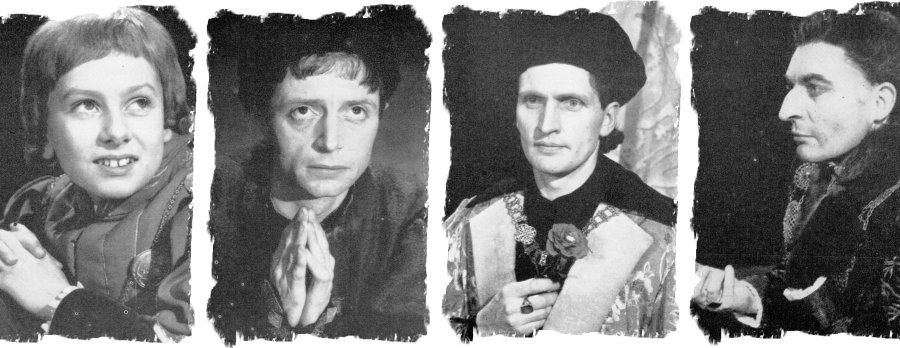

All this is conveyed perfectly by Robert Hardy in the title role. Hardy had a great deal in common with Churchill in addition to a certain physical resemblance. Both had been young prodigies but by 1981 Hardy, like Churchill in 1938, was in danger of being pigeonholed. A leading member of a radical new generation of stage actors in the 1960s, Hardy was already beginning to look old fashioned, a respected character actor who had never quite made it to the superstardom as a leading man many had predicted for him. Like Churchill, he was a man of broad interests - he had studied English under JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis at Oxford and wrote a scholarly work on the longbow. Like Churchill, he built a wide network of friends, including Richard Burton, but, like Churchill, he had a habit of speaking his mind that probably did little to help his career.

So Hardy's Churchill is a rare melding of actor and part. If Hardy sometimes seems a bit overdramatic, even histrionic, well, so, it must be said, did Churchill. Winston really did talk to his closest friends in private as if he was making speeches in the Commons, or as if he expected his clever, well-crafted asides to be quoted - it just so happened that many in his circle were keeping detailed diaries. He could indeed be very emotional, as Hardy demonstrates, even if those emotions were usually shallow. For the most part ebullient, and evidently great fun when at his most bubbly, he was also subject to periods of deep depression. His fits of anger were usually short lived, rarely festering into a permanent grudge: it is to his credit that, when he later attained power, he still employed Chamberlain and many of the "Appeasers" who had treated him badly in his Wilderness Years, even when he was criticised for doing so.

Although several distinguished actors have played Churchill since, and been showered with Awards for their portrayals, it is Hardy's performance those who have seen it tend to remember most vividly. He was asked to repeat it again and again in lesser productions, and it is the part with which he is now probably most associated. It is a great missed opportunity that the money was never there for a full sequel to Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years with Hardy in the lead. It would have been fascinating to see a more mature Hardy tackle a more mature Churchill at length through the "Finest Hour" and beyond.

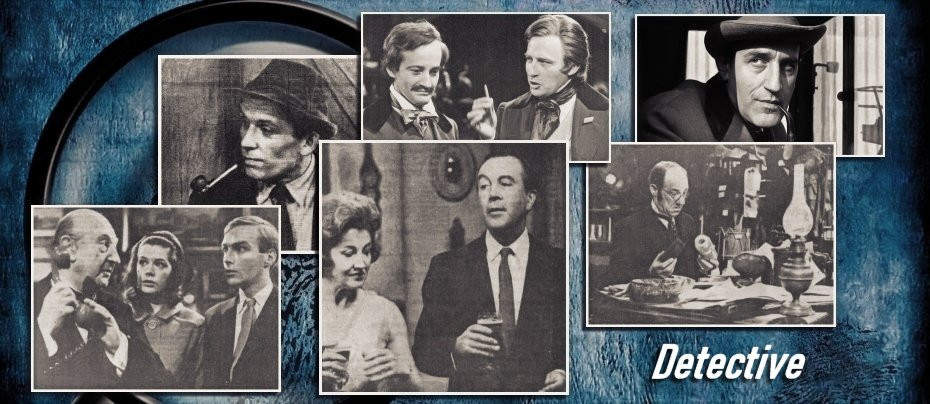

Yet Hardy is only one of an outstanding cast, quite a few of whom bear at least a passing facial resemblance to their historical counterparts, which is a refreshing change.

Top of the list, it is quite uncanny how Eric Porter looks exactly like Neville Chamberlain, whom he plays. Always an actor of great presence and subtlety, this may be the finest performance of his career. Fussy and arrogant, his Chamberlain is the antagonist of the piece but no villain. In a telling scene, his point of view is stated fairly: a reasonable man who wants what his best for his people, he naturally assumes Hitler wants the same. We now know how naive that is, but it is the assumption of a fundamentally decent man who assumes the decency of others. It tends to be forgotten that Chamberlain was a sincere social reformer who, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, had saved the British people from the worst effects of the Great Depression and who, as Prime Minister, viewed foreign affairs as an annoying distraction from what he saw as his really mission of making their lives happier. He deserves to be remembered more charitably than he usually is.

Although he is all but forgotten now, Stanley Baldwin was the dominant and defining politician in Britain between the Wars. A skilled operator who would have impressed Machiavelli, he was careful to hide this behind the facade of a bluff, honest, no-nonsense Englishman, not that intelligent perhaps but overflowing with good humour and common sense. Peter Barkworth brings him to life quite brilliantly. It is the portrait of a man almost anyone would assume was a good chap whose fingerprints would never be found on a murder weapon. They never were. His great scene is an innocuous croquet match in which the courtesy and decency of his conversation are contradicted by the casual ruthlessness with which he plays.

Siân Phillips does not look like Clementine Churchill but captures her essence very effectively. The Churchills had an odd marriage but it worked well. Clementine's practical nature was a much needed check on Winston's romanticism and her shrewd judgement of people a useful corrective to his tendency to trust too easily, even if she was sometimes wrong. Largely neglected by his parents as a child, Winston developed an excessive need for companionship and affection as an adult - which Clementine was perhaps not the best person to satisfy. In fairness, while Churchill was great company at his best, even his closest companions could find him demanding, self-centred, and exasperating on occasion. One can understand why Clementine was often exhausted and frequently needed breaks away from him. However, the script is almost certainly wrong to imply that she had affairs during these breaks, and that Churchill knew and turned a blind eye.

The now obscure Sir Samuel Hoare is used as an amalgam of several members of the Baldwin-Chamberlain Cabinets who were hostile to Churchill but at least he gets a dignified conclusion to his character arc. The real Sir Samuel was something of a cold fish, so Edward Woodward, of Callan fame, was far from obvious casting, but he makes the most of the opportunity to prove his versatility. Callan fans might appreciate the in joke when Sir Samuel turns to Lord Hailsham for legal advice - and Hailsham is played by Geoffrey Chater, who was so memorable as Callan's superior, Bishop.

Two rising young stars of the time did their careers no harm with wholly credible portrayals, Nigel Havers as Churchill's argumentative scapegrace son, Randolph, and Tim Pigott-Smith as Bracken, Churchill's slightly mysterious financial supporter and political apprentice.

In a neat parallel, David Swift plays Churchill's legendary scientific adviser, Professor Lindemann, while his brother Clive plays Chamberlain's closest adviser: sadly, the two brothers never share a scene but, as always, both earn their cheques.

Talking of actors who always earn their money, Frank Middlemass is wholly believable as the ultra-aristocratic 17th Earl of Derby: a delicious line about furniture sums up his whole character. Peter Vaughan looks the part of Baldwin's legal enforcer, Sir Thomas Inskip. It is a pity we do not see more of Stratford Johns as Lord Rothermere, Norman Bird as the respected Sir Maurice Hankey, Nigel Stock as a British Admiral sympathetic to Hitler, and Sam Wanamaker as Churchill's closest American friend, Bernard Baruch. David Markham, in one of his last roles, looks the part as Churchill's cousin, the Duke of Marlborough, as does Terence Rigby as a socially ambitious cotton magnate, even if both characterisations may be slightly unfair to their real life counterparts. Paul Freeman ('Raiders of the Lost Ark') is appropriately tightly wound as a civil servant obsessed with German rearmament, while Moray Watson is a more level headed officer who shares his concerns. Walter Gotell, the relatively reasonable KGB General in the Roger Moore Bond films, is fair minded as a Secretary of State for Air who knows there is a problem but feels he can do nothing. Richard Marner has a cameo as a German officer - good preparation for his later role in Allo 'Allo.

Another interesting casting connection: German actor Gunter Meisner, who appears briefly as Hitler, played the same role in The Winds of War - in the sequel to which Hardy made one of his subsequent reappearances as Churchill.

Only Richard Murdoch - Arthur Askey's sidekick "Stinker" Murdoch - is slightly miscast as Lord Halifax. There is nothing wrong with his performance as another of the slightly vague old men which were his stock in trade at that point - immaculately delivered, as always, but out of place here. Halifax was a much younger man and famous for his shrewdness, which, combined with his deep Christian faith, led to Churchill nicknaming him "the Holy Fox."

There is very little "action" as such in Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years. It is a character driven piece, and, while character is revealed by action, here the action is mostly dialogue, with some clever little details for the keen eyed. Such a "talky" script would simply not be allowed these days, which makes rewatching it for the first time in forty years a double pleasure. It is one of the last products of the true "Golden Age of British Television," when producers were not afraid to assume their viewers were grown up enough to pay attention and not expect to have everything spoon-fed to them.

It is therefore regrettable, but somehow symbolic, that this classy piece of television did nothing to prevent Southern losing their franchise soon after it was shown. As it is, it remains an honourable monument, not only to Southern but to ITV's strong competition with the BBC in historical drama during its glory years.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 19th, 2022. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.