The Day of the Triffids

1981 - United KingdomThe BBC’s 1981 six-part adaptation of The Day of the Triffids stands as a prime example of an atmospheric, intelligent, and reverent realisation of classic science fiction recreated for the small screen. A darkly lyrical vision by one of Britain’s foremost literary science fiction writers, John Wyndham, was brought vividly to life by a team of television professionals who approached the material with both creative enthusiasm and profound respect. The result was a landmark production that has endured as a touchstone of the genre.

The origins of Wyndham’s seminal novel were curiously humble. In 1950, while out walking through a tangled Hampshire country lane, John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris observed the thorny, awkward movement of blackberry brambles swaying in the wind. To his wife Joan, he wryly remarked, “By Jove, if those things could walk and think, they’d be dangerous.” That simple thought would germinate into one of the most unsettling stories of speculative fiction ever penned. Less than a year later, Collier’s magazine in New York began serialising the tale under the title Revolt of the Triffids, and a minor classic was born.

Between the novel’s 1951 publication and its eventual television incarnation, The Day of the Triffids underwent various adaptations—some more successful than others. The BBC adapted it for radio, it was serialised on Woman’s Hour, and in 1962, it received a rather underwhelming Hollywood treatment, starring Howard Keel and British actress Janette Scott. That film, while fondly remembered in some circles, lacked the novel’s introspective tone and subtle menace.

It wasn’t until 1979 that the idea of a faithful TV adaptation gained serious traction. Producer David Maloney, a seasoned hand in science fiction television thanks to his work on Doctor Who and Blake’s 7, championed the idea. Douglas Livingstone was brought on board to adapt Wyndham’s novel for the screen. Though the BBC admired Livingstone’s scripts, the production’s extensive requirements—ranging from numerous outdoor locations to complex special effects—proved too expensive to green-light at the time.

That impasse was broken two years later, in 1981, when a co-production deal was struck between the BBC, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and American cable network RCTV Inc. This international funding arrangement allowed the series to proceed, with Livingstone reworking his original six 26-minute episodes into three longer instalments for overseas broadcast, while maintaining the six-part format for UK audiences.

Livingstone’s adaptation remained commendably faithful to Wyndham’s bleak vision. His most notable changes were relatively minor: updating the 1950s setting to an ambiguous near-future, and modifying the character of Josella Payton—from the author of a provocative novel titled Sex Is My Adventure to a more modern, career-minded woman. While Wyndham himself may have frowned upon this change, it was a shrewd move for a drama intended for a broad family audience.

Director Ken Hannam, an Australian filmmaker with a deft touch for character and mood, adopted a deliberately low-key and realistic tone in his approach to filming. Hannam’s direction was understated, evoking a world quietly descending into chaos, and effectively capturing Wyndham’s distinct blend of science fiction and social commentary. The result was a story that felt eerily grounded despite its fantastical premise.

At the heart of the drama is Bill Masen, a former Triffid farmer who begins the story recovering in hospital from temporary blindness caused by a Triffid sting. While shielded from the global catastrophe—a mysterious cosmic light display that blinds the majority of the world’s population—Masen emerges to find a society in ruin. Sightless masses wander the streets, and the mobile, venomous Triffids, once cultivated for their valuable oil, are now free to prey on humanity.

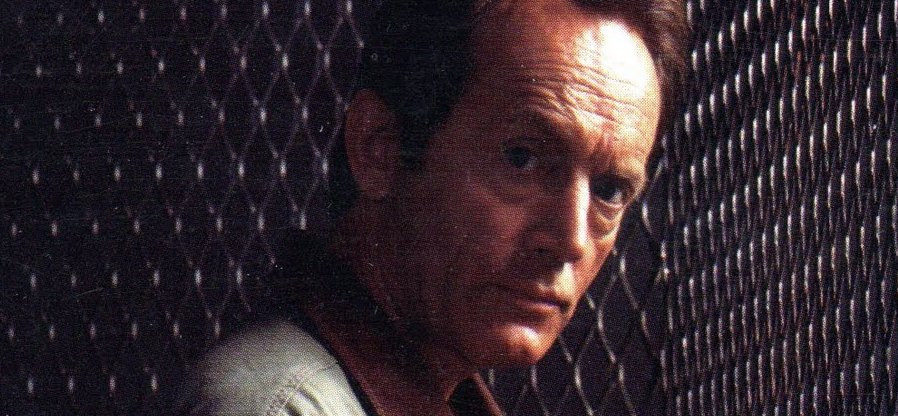

John Duttine’s portrayal of Masen is quietly brilliant. He infuses the character with a convincing, everyday heroism—pragmatic, resourceful, and deeply humane. Emma Relph, daughter of renowned film producer Michael Relph, is equally strong as Josella, bringing intelligence, warmth, and subtle vulnerability to a character who might easily have become a stock figure in lesser hands.

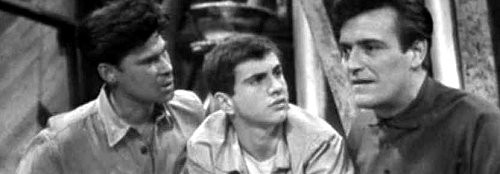

The supporting cast is equally well chosen. Stephen Yardley brings strength to the role of John, David Swift offers a memorable turn as Dr Soames, and Maurice Colbourne excels as the charismatic and dangerous Bill Coker. Their performances ground the series, adding emotional heft to a story of societal collapse and survival.

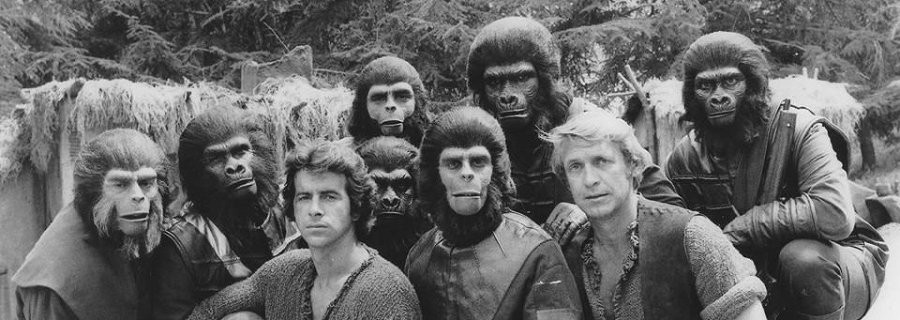

Of course, the true stars of the series are the Triffids themselves—strikingly realised and impressively articulated for the time. Lurking somewhere between science fiction horror and ecological parable, the Triffids are never fully explained. Their origins remain mysterious, their intelligence ambiguous, and their menace palpable. As with Wyndham’s novel, they are treated less as monstrous invaders than as a deadly force of nature, capitalising on humanity’s sudden vulnerability.

What makes the 1981 adaptation so enduring is its careful balancing of scale and intimacy. While the implications of the disaster are global, the storytelling remains focused on individuals—people trying to survive, to regroup, and to find hope in a world turned upside down. The production design, while modest by today’s standards, is effective and evocative, with the eerie emptiness of post-disaster Britain brought chillingly to life.

The Day of the Triffids is, in many ways, a textbook example of how to respectfully adapt literary science fiction for television. It captures the philosophical and emotional weight of the original work without sacrificing narrative tension. It also helped pave the way for the wave of intelligent, idea-driven science fiction dramas that emerged on British television throughout the 1980s.

Low-key yet ambitious, faithful yet thoughtfully adapted, this BBC version remains the definitive screen treatment of Wyndham’s novel. It is a chilling, thoughtful, and expertly realised adaptation that still resonates over forty years later. The triffids may be slow-moving, but their cultural legacy, like their creeping tendrils, continues to grow.

TRIVIA:

The Triffid's appearance remained a closely guarded secret until the transmission of the first episode, although a glimpse was given on the cover of the Radio Times dated 5-11th September 1981 showing the edge of its head as it menaces Bill and Jo.

Whyndham would almost certainly have approved of special effects man Steve Drewett’s design for the Triffid’s, which was based on research into real life parasitic plants. Drewett’s training at the Natural History Museum showed in the form of the looming, lumbering eight-foot monsters, clattering their armoured mandibles and slashing out with their flailing stings.

The long tubular sting was, in fact, Drewett's idea. It explained how the Triffids disabled and fed off their prey, something that the novel was vague about. Having read the book he decided to make the plant look initially attractive so that its victims would be drawn nearer to look at it.

A Triffid was operated by a man crouched inside. The knotty bowl, based on the ginseng root, was made of latex with a covering of sawdust and cord while the neck was fibreglass and continued down to the floor, where it joined with the operator's seat. A flexible rubber head, coated with clear gunge, surmounted the plant.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 7th, 2018. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.