Casanova

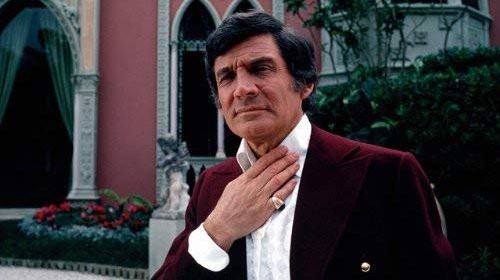

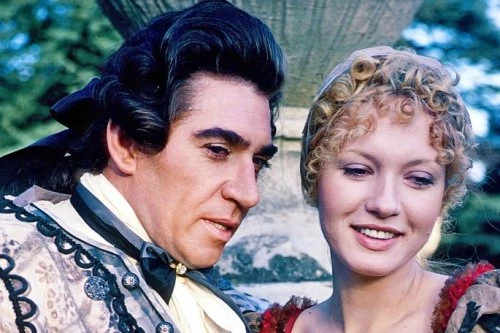

1971 - United KingdomDennis Potter’s Casanova, first broadcast in 1971 by the BBC, remains one of the more audacious pieces of television drama of its time. Starring Frank Finlay in the titular role, the series painted a complex, reflective, and often troubling portrait of Giacomo Casanova, not merely as the infamous womaniser of legend, but as a man imprisoned (both literally and emotionally), introspecting on a life consumed by sexual pursuit, loneliness, and the inexorable passing of time.

At six episodes, Potter’s Casanova was as much a psychological exploration as it was a costume drama. The decision to intercut between Casanova’s imprisonment in Venice and his reminiscences of various amorous encounters was a bold storytelling device that gave the series an almost confessional tone. Finlay’s performance was restrained, melancholic, and at times pitiful, far from the rakish caricature audiences may have expected. In many ways, the series did for Casanova what The Singing Detective would later do for Potter’s own alter ego: strip away fantasy to expose the fragility beneath.

Yet it was not the dramatic structure or historical reflection that attracted headlines — it was the explicit (for the time) sexual content. Casanova featured nudity and sexual situations that, while relatively tame by today’s standards, were groundbreaking in the early 1970s. It was part of a wider cultural shift where British television was beginning to grapple more openly with sex, desire, and the body - subjects previously confined to innuendo or art-house cinema.

This boldness did not go unnoticed, and one of the most vocal opponents of the series was none other than Mary Whitehouse, Britain’s self-appointed moral guardian. As founder of the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association (NVALA), Whitehouse had by then become a familiar figure in British cultural life. Since the mid-1960s, she had campaigned tirelessly against what she perceived as the moral degradation of British society, particularly on television. Her targets were many, ranging from the BBC, which she often accused of “pandering to the permissive society”, to individual creators like Potter, whom she held responsible for what she saw as a dangerous erosion of public decency.

Whitehouse’s criticisms of Casanova were typical of her broader crusade. She lambasted the series for its frank depiction of sexuality and its inclusion of nudity, which she argued would corrupt public morals and degrade women. In her view, television was a powerful social influence, and those who made it had a duty to uphold certain standards.

Potter, by contrast, saw the inclusion of sex and nudity not as gratuitous but as essential to the narrative. His writing often challenged traditional notions of morality, identity, and repression, and he was no stranger to controversy. By 1971, he had already raised eyebrows with works like Vote, Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton, and he would continue to provoke and innovate until his death in 1994. Potter used the medium of television not merely to entertain but to interrogate, and Casanova was a prime example of his subversive intent.

It is worth noting that Casanova did not appear in a vacuum. The early 1970s were a time of significant cultural transformation in Britain. The so-called "permissive society" was in full swing: the censorship laws had been relaxed; Oh! Calcutta! was playing to packed audiences; and cinema had already begun to explore sex more openly. What Casanova did was to bring this new openness to the small screen - a space still, at the time, considered by many to be the preserve of family entertainment.

So, was nudity on television acceptable to contemporary audiences? The answer is both yes and no. There was clearly a growing appetite for more mature themes and an increasing recognition that television could and should reflect adult concerns. Yet there remained a significant segment of the population, often represented by Whitehouse and her supporters, who viewed such developments as a betrayal of traditional values. In that context, Casanova became a cultural battleground, a litmus test for what British society was willing to countenance in its living rooms.

In retrospect, Casanova feels less sensational than it did at the time. Its real power lies not in the nudity or sex, but in its psychological depth and its willingness to question the very myths it depicts. As with much of Potter’s work, it was ahead of its time—too frank for some, but a necessary challenge to the limits of television for others.

Today, one can see Casanova as a pivotal moment in British broadcasting—a point where television began to acknowledge, with uneasy honesty, the complexities of human sexuality. Whether one sees that as progress or decline perhaps depends on which side of Mary Whitehouse's moral line one chooses to stand.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on May 18th, 2025. Written by Laurence Marcus for Television Heaven.