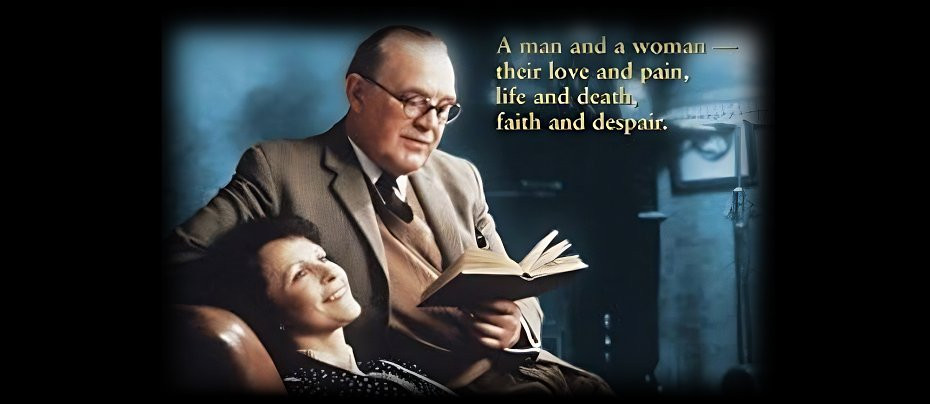

Shadowlands

1985 - United Kingdom"strong characterisation and intelligent dialogue"

Shadowlands review by John Winterson Richards (December 2023)

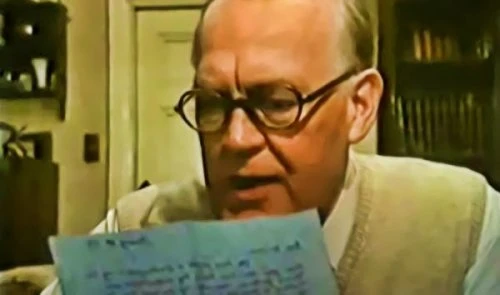

It was the recent passing of the great Joss Ackland, an actor who was never really given the recognition he deserves, that prompted your reviewer to revisit the first and best production of Shadowlands, in which Ackland plays the philosopher, theologian, novelist, poet, and Professor CS Lewis. It was only after I finished rewatching it for the first time in several years that I realised it was the Eve of the Sixtieth Anniversary of Lewis' own passing - no more than a coincidence, but the sort of coincidence that seems to happen a lot.

The BBC Shadowlands, directed by Norman Stone, is arguably Ackland's finest hour and a half as an actor, as well as having an interesting history of its own. Based on a first draft by Stone and Brian Sibley, the final script was written by William Nicholson, who subsequently adapted it into an Award-Winning stage play starring Nigel Hawthorne and Jane Lapotaire, which was in turn adapted, again by Nicholson himself, into the script for a major feature film, also of the same name, directed by Lord Attenborough and starring Sir Anthony Hopkins as Lewis.

It is in this cinematic incarnation that most people know Shadowlands. It is a great film, one of Attenborough's best, anchored by what is surely one of Hopkins' half dozen most accomplished performances. That having been said, it is not denigrating the film in any way to say that Stone's original version is far better because it is much closer to the real story and because Ackland is much closer to the real CS Lewis.

Where Hopkins plays him as a somewhat sheltered academic, propelled into the outside world late in life by his love for an extroverted woman, the historical Lewis projected a more outgoing, ebullient personality, which Ackland evokes very convincingly, and, although he had attained a certain level of comfort and security in his life by the time the story in Shadowlands opens, his path there had been full of incident and unexpected turns. The most unexpected led him from militant atheism to becoming, in his own words, the most reluctant convert to Christianity in England. A long late night walk around the grounds of Magdalene College with his friends JRR Tolkien and Hugo Dyson played a pivotal role in the process.

Much, but by no means all, of Lewis' eventful journey is described in his autobiography Surprised By Joy, a title that was subsequently to take on an ironic double meaning, since it also sums up with uncanny prescience the events dramatised in Shadowlands, most of which took place after its publication - another of those coincidences that happen a lot.

Those events begin with Lewis, secure in his Oxford Fellowship and in a pleasant bachelor home shared with his brother, Warren, generally known as "Warnie." One day Lewis mentions, perhaps a little too casually, that among many fan letters he has received as a result of his writing, especially the Narnia novels, one from an apparently eccentric American lady stands out as unusually interesting. It just so happens that she is visiting England and would like to meet him. Since she is married, Warnie acts as chaperone when they have tea together in the Randolph Hotel in Oxford.

Joy Davidman Gresham is indeed a surprise. Like Lewis, she is a poet and a convert to Christianity, but in other respects she is very different from him. Jewish by birth, she had for many years been an active Communist. She intrigues the small-c conservative Lewis. He invites her and her sons, David and Douglas, to spend Christmas with him and Warnie.

It was only when they are on friendly terms that Joy reveals what might have kept them at a distance had she revealed it before, that she is alone with her children in England because her marriage is collapsing and her husband is with another woman. Interestingly, Lewis, a strong advocate of lifelong Christian marriage, says nothing to discourage her divorce.

Nevertheless, they remain no more than friends. When Joy has problems with her visa, Lewis offers to marry her in a civil ceremony in order that she and the children can remain in the United Kingdom, on the strict conditions that it is kept secret and that it is understood that it is a marriage in name only. This leads to the strange situation in which people suspect that she is Lewis' secret mistress when the real secret is that they are lawfully married but celibate.

It is when Joy discovers she has terminal cancer that Lewis realises his feelings for her are more than Platonic and proposes a full Christian marriage. After the ceremony, the clergyman offers a prayer of healing and soon after Joy goes into a remission that amazes everyone. They enjoy an extended period of great happiness together, but they know it is only temporary. Eventually the cancer returns and Joy's death leaves Lewis devastated.

The scenes that follow are the most powerful, with Ackland doing some of his very best work. The experience of the months that followed losing Joy, in every sense of the word, prompted Lewis to write the last of his great works, A Grief Observed, which is quoted in Shadowlands without being mentioned directly. This is a book of such brutal honesty that Lewis published it under a pen name in order to distinguish it from his more optimistic Christian works. Its unflinching attitude to death, which makes it a tough read, has also made it a great comfort to many people, both believers and non-believers, mourning the loss of a loved one. The Attenborough film quotes some of the blunter passages out of context to imply, falsely, that Lewis lost his faith, when the book as a whole, as well as his private correspondence at the time, make it clear that he did not, on the contrary emerging with a deeper Spiritual understanding.

What he did reject was the more sentimental consolations of religion which in Shadowlands are put into the mouth of a straw man clergyman friend, a fictional character who seems to be an amalgam of several of his believing friends, just as another fictional character is an amalgam of several of his unbelieving friends. This is a permissible literary device, even if one feels an experienced clergyman would know how to handle such situations better. The point is that even firm faith in the possibility of Heaven for the deceased does little to alleviate the sense of loss at their physical absence felt by those left behind, a truth some religious people may find it hard to admit.

The original version of Shadowlands is more accurate than the feature film by ending with a beautiful metaphor on the true nature of faith. In a heartbreaking scene, Joy's son Douglas says he does not believe in Heaven, but Lewis, without answering directly, subsequently references how he found faith around the same time he learned to dive. He promises to teach Douglas how to dive, implying that they will discover or rediscover faith together. That is a good place to end, so the script does not go on to show how Lewis did indeed become like a father to the boys, especially Douglas, who became a Christian and whose book Lenten Lands is a major source for Shadowlands. Lewis was also supportive of David's choice to explore his Jewish heritage.

It is in general one of the ways in which the BBC Shadowlands is superior to the Attenborough film that it is willing to engage closely with the religion which is at the core of Lewis' life and work. One cannot understand Lewis without understanding this - just as one cannot understand his friend Tolkien without understanding his faith, a point one recent film biography of Tolkien seemed to go out of its way to avoid. The Attenborough film also cut poor David out completely.

It has to be noted that all the versions of Shadowlands are structured as a classic love story, ignoring a lot of subtext. For example, it seems that Joy set her sights on Lewis at long distance before they ever met. It also has to be said that several of Lewis' decisions seem at odds with his professed intention of keeping her at a respectable distance.

Ackland is perfect at conveying the hearty beer-drinking Englishman - actually Irishman of Welsh origin - Lewis aspired to be while at the same time hinting at the vulnerability and caution of a man who had experienced a difficult first three decades. Claire Bloom is a luminous Joy. Where Debra Winger made her very assertive in the modern style in the Attenborough film, Bloom is better at suggesting that she is, in her way, just as damaged beneath a veneer of self-confidence as Lewis himself. She is also better at projecting the fierce intelligence that was necessary to captivate a man like Lewis. There is nothing wrong with Winger's performance, but one never forgets one is watching a Hollywood actress. Character actor David Waller plays Warnie credibly as a Nigel Bruce-type Doctor Watson to Lewis' Holmes. Stressing Warnie's role as a kindly, humane presence among spiky intellectuals, the script makes no mention either of his own considerable achievements as a historian or of his struggles with alcoholism.

It is only to be expected that the production values and photography are superior in the subsequent feature film, but this should not detract from the fact that the location work in the BBC version is still excellent in its own right, especially by the standards of its day.

In any case, what matters more is the accuracy and dramatic impact of the story, and here the television version wins on both points. More than that, it proves that, far from being alternatives that the scriptwriter must mediate, accuracy and dramatic impact are complimentary, because fact often gives us better stories than fiction and the emotional power of stories is increased when the viewer knows they are true. Shadowlands is also another reminder that television does not need to be noisy and flashy to attract attention, but, quite the contrary, strong characterisation and intelligent dialogue that is prepared to deal seriously with serious issues can be far more compelling. Sadly, one cannot imagine something like it being commissioned by the BBC today. Stone has since made another film about Lewis but had to do so independently.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 12th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.