Anzacs

1985 - AustraliaFollowing up the global success of the "Australian New Wave" of the 1970s and 80s in the cinema, Australian television produced a number of high quality "miniseries" that attracted similar acclaim and cemented Australia's position as a rising cultural power. Each of the most notable of these, Anzacs, Vietnam, and Bangkok Hilton, was a showcase for at least one rising Australian star who later went on to international fame.

It is no coincidence that Anzacs, the first of these prestigious series, covers some of the same ground as Gallipoli, the film which is usually considered the zenith of the cinematic "New Wave." It is based on a true story dear to all Australians, even if its meaning and significance are open to debate. It is the story of Australia's contribution to the First World War, the Great War.

All nations have their founding mythologies. The United States, for example, takes pride in the notion that it was started by a bunch of plucky farmers fighting for their "freedom" against the arrogant Brits - even if the truth is a lot murkier. One suspects that many Australians rather regret that they did not get to fight a similar War of Independence against Britain. Instead, they date their nationhood from the time Australia united to mobilise its own army of tough, self-reliant, egalitarian outdoorsmen, bound by an unbreakable "mateship," in the common cause of "freedom" - only to have it misused by said arrogant Brits.

This "Anzac Legend" is very powerful in Australia, where Anzac Day, the anniversary of the day the Australians landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula, is a national holiday. Like all the best legends and mythologies, the Anzac Legend has a strong foundation in fact but has changed over time to suit the prevailing ideology: at first the emphasis was on the common cause of "freedom" - but in more cynical times the emphasis shifted to the alleged misuse of Australian troops by British Generals. Anzacs is very much a product of the latter.

History is clear that a deep, unforced patriotism led to a flood of volunteers from the Dominions to support the United Kingdom at the start of the Great War. Sympathy for the small nations of Serbia and Belgium invaded by the Central Powers was also real and widespread in the younger nations of the British Empire. The first contingents from Australia and New Zealand were grouped together in the "Australian and New Zealand Army Corps" (ANZAC), which was deployed in the Gallipoli Campaign against Turkey. There, the Australians and New Zealanders soon established their reputation as superior fighting men, a reputation their countries have enjoyed ever since - even if it must in fairness be noted that the Australians also developed a reputation for indiscipline.

Despite their magnificent efforts, the Gallipoli Campaign was mismanaged until it ended in evacuation. The Australian Divisions were then sent to the Western Front in France where they added to their fighting reputation. So there is real substance to the Anzac Legend, even if there is also considerable exaggeration: more of the Anzacs were urbanites than stereotypical bushranger types, there was a definite Australian class system, and the question of leadership is complicated - some of the most infamous mistakes were made by Australian officers, while some British Generals were held in high esteem by the Australians they commanded.

The series follows a group of fictional volunteers who enlisted together in the real life 8th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force - a battalion with an astonishing combat record: three of its members were awarded the Victoria Cross. The basic format of Anzacs was similar to that of the later Band of Brothers, except the Australians, perhaps lacking confidence in the commercial viability of what would otherwise have been an almost exclusively male cast, also included elements of drama on the Home Front.

The first episode sees the Anzacs in Gallipoli, but since this was territory already well covered by the then recent film of that name, the series did not hang around there for fear of comparison. So the bulk of the production, four episodes, is dedicated to the 8th Battalion on the Western Front, including the bloody Battles of the Somme, Passchendaele, and Amiens.

Since Australians take the Anzacs very seriously, it is no surprise that the project went to great lengths to get the military history right. Few films and television series are its superior in this respect. Considerable effort appears to have gone into replicating the actual tactics and procedures of the time. Our heroes do not simply shoot down large numbers of the enemy as they present themselves conveniently one at a time while being wholly unable to aim properly in response. A German advance on the Australians in open country is a particularly fine example of fire and manoeuvre, and it looks entirely credible that our side might lose.

It is interesting to see the name of James Mitchell, the British writer responsible for Callan, in the credits. One suspects he was brought in by the Australians because he shared his fictional character's passion for the details of past campaigns.

Several incidents witnessed by our imaginary Anzacs are real. These include General Kiggell, Field Marshal Haig's Chief of Staff, breaking down when he saw the mud in which he had sent men to fight at Passchendaele, and the "mutiny" of the 60th Battalion - a rare example of men refusing to obey orders because they wanted to be put in the thick of the battle.

The script's treatment of the high command is more questionable. To its credit, it differentiates between the different Generals. Some, like Plumer, are praised. Others are treated unfairly. The notion that the British and Imperial frontline troops were "lions led by donkeys" was still the height of fashion in the 1980s. Serious historians have since taken a far more nuanced view, not least about Haig himself, who is, as usual, portrayed unsympathetically in Anzacs. The series is, however, quite open about David Lloyd George's rather unscrupulous plotting against him.

The script is particularly unfair to the Australian Major General Sir William Bridges, who, it is implied, was out of touch with his own troops at Gallipoli. In fact, Bridges was noted for his frequent visits to the front, where he was killed by a sniper a few days after the scene in question - one of seventy British and Imperial Generals who died on active service during the War: if any of them were "donkeys," they were brave donkeys.

The battle scenes are superbly mounted. If some use only a relatively small number of extras, the fact is usually hidden with great skill. The gore and squalor is toned down, necessarily for television of the day, but one still gets a vivid sense of the horror of it all. The script even engages, discreetly, with the dark side of the Anzac Legend, a reputation among other Allied troops for looting and for shooting prisoners. The former is treated as a lark while the latter is just the work of one very bad apple, but Anzacs is brave to mention them at all.

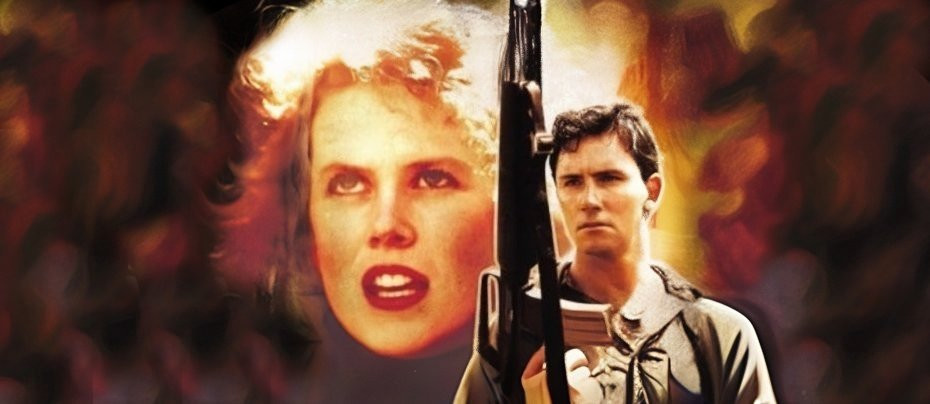

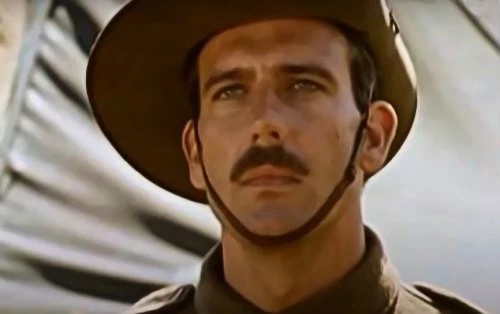

The strength of the production rather overshadows the cast. The project was intended to promote a rising generation of Australian actors. However, Andrew Clarke, who played the impossibly perfect principal protagonist, never quite turned his popularity in Australia into an international career, and two of the other young stars, Megan Williams and Jon Blake, both died tragically early.

Perhaps surprisingly, the "breakout" actor was Paul Hogan, who was relatively low on the bill in what was supposedly his first big dramatic role. In the event, it was really not that dramatic: he was obviously brought in as comedy relief, playing a character similar to that he had usually played in his recently ended comedy series, and which he later played in most of his film roles, such as Crocodile Dundee - the stereotypical tough, cunning, warm-hearted unreconstructed larrikin. He managed to steal every scene in which he appeared but without unbalancing the drama. His likeable screen persona was already known outside Australia, but it was Anzacs that showed he had the ability to handle a big role in a major project and soon led to greater things.

The best performance, however, is that of Tony Bonner as a decent officer whose nerves are gradually shredded: it is an intensely moving demonstration of the hidden cost of war. Aussie stalwart Bill Kerr strikes an authentic note as the respected General Monash, and Shane Briant is subtle in his portrayal of an Australian of German origins.

In retrospect, Anzacs probably says more about the Australia of the 1980s than about the Australia of the Great War. Most Australians retained a genuine affection for "the Mother Country" until fairly recently. As late as the 1960s, young Australian intellectuals complained of a "cultural cringe" towards Britain - and moved there. However, many mainstream Australians felt disappointed when the British did not join them in the Vietnam War and then positively betrayed when Britain joined the EEC. Australian nationalism and Republicanism began to grow. By the time Anzacs was made, Bob Hawke was Prime Minister, and he would be succeeded by the more aggressively anti-British Paul Keating. They enjoyed great support in the Australian Cultural Establishment and this is reflected in Anzacs.

Some of the attitudes expressed by the characters were undoubtedly around during the Great War, but probably not as prevalent as Anzacs implies. The Anzacs were generally proud to have fought alongside Britain in 1914 and their children were proud to do it again in 1939. The series was therefore very much of its time, but has nevertheless aged well as an outstanding piece of television craftsmanship and a worthy tribute to some great fighting men.

Review by John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found here: John Winterson Richards

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 23rd, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.