Vietnam

1987 - Australia‘Vietnam is such a compelling drama’ – ‘Kidman steals the show’

Review: John Winterson Richards

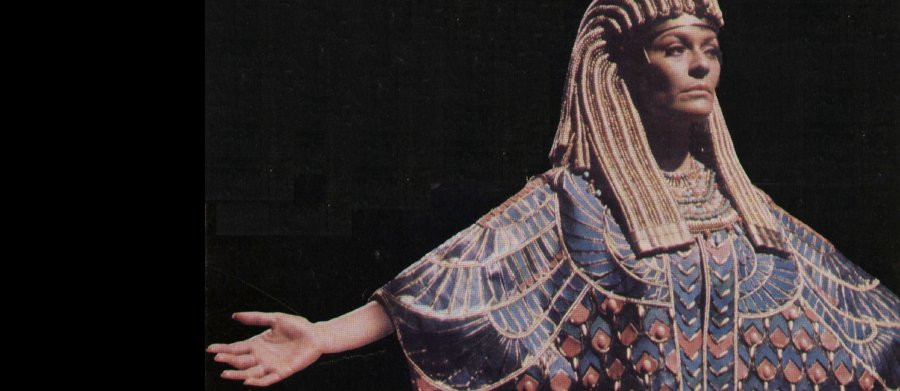

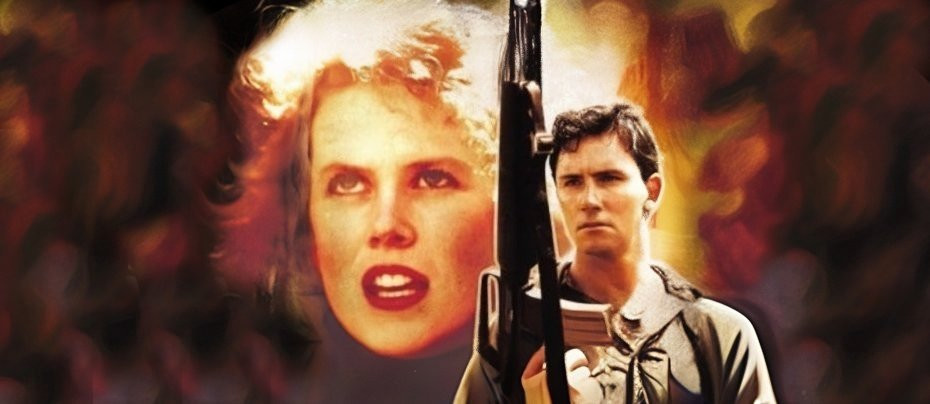

A casual line of dialogue in Vietnam references the beginning of what became the New Wave in Australian cinema - which is ironic because the mini-series itself is in retrospect a great example of how that wave spilled over into television, following Anzacs and soon to be followed by The Bangkok Hilton. It is also notable as the project that introduced an astonishingly talented teenager called Nicole Kidman to the world.

In spite of its title, Vietnam is less about Vietnam than it is about Australia, and the cultural and social changes there during the 1960s. To be honest, that rather heavy handed line about Australian cinema is typical of a definite lack of subtlety in the script's approach to those changes, but there is no doubt that the Australia that was positively eager to support the United States in the Vietnam War was not the same Australia a few years later and Vietnam provides a neat, if somewhat biased, summary of complicated events that serve as a backdrop to the drama.

Since Australia's participation in the War is largely forgotten today, at least outside Australia, Vietnam can be criticised for not doing more to explain why it was, initially, considered a good idea at the time. The Fall of Singapore to the Japanese in 1942 had posed a real threat to Australia and it was the United States rather than the United Kingdom on whom Australians began to rely for their security. When the rapid Post-War expansion of Communism in East Asia and the Eastern Pacific posed a similar threat, a genuine threat that Vietnam plays down, Australians felt it was an assertion of their own nationhood to take the initiative in partnership with their new ally. What soon became apparent, and this is a point Vietnam makes much better, was that their ally had absolutely no idea what it was doing (not a personal opinion but the conclusion the "Pentagon Papers," an internal study begun as early as 1967, which showed that the United States went in to Vietnam with no political or military strategy worthy of the name).

The impact of the growing realisation that this was the case is the basic theme and spine of the story in Vietnam. It combines three separate plotlines - a family drama, a war drama, and a political drama. To be honest the last does not always sit easily with the other two because it detracts from the perspective of the "ordinary family" and the "ordinary soldier" when the paterfamilias just happens to be a senior adviser to the Prime Minister.

Douglas Goddard (Barry Otto) is a veteran of the Second World War and a political conservative acutely protective of his social status, a somewhat cartoonish representation of the traditional Australia of the 1950s. While he is hardly a domestic ogre, and it takes an affair to make him the bad guy in what happens, he talks down to his wife, Evelyn (Veronica Lang) and fails to notice how unhappy she is. Their son Phil (Nicholas Eadie) is something of an aimless drifter who does not want to be conscripted but, in spite of his father's advice, does nothing to avoid it. Daughter Megan (Kidman) is a bratty rebel, self described "jail bait," an equally cartoonish representation of the 1960s, who, viewed objectively, is selfish and just as much the slave of the fashions of her generation as her father, and would come across as quite unpleasant were it not for Kidman's precociously mature performance.

It is not difficult to predict what is going to happen to each of these four, and it does. What keeps Vietnam compelling is the skill with which each of their predictable stories is told.

The war drama, filmed mainly in Thailand, is particularly well done, especially given the limitations of a television budget. There is a very powerful scene with a land mine and a clever air of unreality when Phil becomes involved in "black ops," causing him to lose his moral compass as he simply goes with the flow of the insanity around him.

The family drama is also moving in spite of the stereotypes. It is sad to watch the characters become estranged, even if the script seems to imply that there is a necessity to the breakdown of their relationships. Yet even if this family structure is flawed, they are none of them bad people and one is left feeling that it only needed a bit more effort at communication to make things work.

The political drama is more perfunctory, in part because the writers wear their politics on their sleeves - which in the Southern Hemisphere television industry are the same sleeves as they usually are in the Northern Hemisphere. A succession of Liberal, i.e. conservative, Prime Ministers are portrayed in person but presented as little more than cardboard cutouts while the anti-War Labour Prime Minister Gough Whitlam is shown reverentially in archive footage. His election in 1972 is symbolically a moment of healing for the Goddards, and, by implication, for Australia as a whole. The reality is that Whitlam was, and possibly remains, the most controversial Federal Prime Minister in Australian history, and his win in 1972 was not a moment of reunification but a swing of only 3% that was reversed more decisively a few years later. Bob Hawke, who was the Labour Prime Minister at the time Vietnam was made, is also given a respectful cameo in archive footage.

The script is at least honest about the terrorist nature of the Vietcong. Yet it is the Americans who are shown, crassly, as the really bad guys. It has to be said that My Lai and the Phoenix Programme happened, so it is fair to reference them, even if they are not mentioned directly by name, but Vietnam should not be mistaken for a comprehensive analysis of the War and its consequences. While it is in the nature of a historical drama to pick out the most dramatic elements from history, there is a danger that viewers who know little else about the period might be left with seriously inaccurate impressions.

The anti-War movement is romanticised quite shamelessly and made to look more popular than it was. Supposedly sympathetic characters cheerfully chanting the name of the head of a brutal Marxist dictatorship has not aged well. Nor has the typically Eighties celebration of the "sexual revolution." Scenes with the then 18-year old Kidman playing a 15-year old now make very uncomfortable viewing.

It is all the more necessary to stress these reservations because Vietnam is such a compelling drama. Kidman steals the show. Almost immediately afterwards she went on to even greater success with another great Australian miniseries, The Bangkok Hilton, and the feature film Dead Calm from the same producers as Vietnam. However, rewatching Vietnam for the first time in more than three decades, one is struck by how Otto and Eadie are just as good. Although Douglas is in some ways the antagonist, Otto invests him with humanity and vulnerability: when he is nagging his son to get his act together and go to University, one sees the veteran getting the better of the patriot in wanting the boy to avoid being conscripted. Eadie, in his late twenties at the time, was perhaps a bit too old for the early scenes, but he is at his best towards the end when Phil returns home with PTSD: while one sees why the Vietnamese wife of a comrade crippled in the War is very frightened of him, he never loses our sympathy.

Whether it was during the Vietnam War - or the Second World War or the First - that Australia "came of age" as a nation might be a matter for debate, it was during the 1980s, thanks in large part to Vietnam, that Australian television matured into a global force in television drama.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on May 30th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.