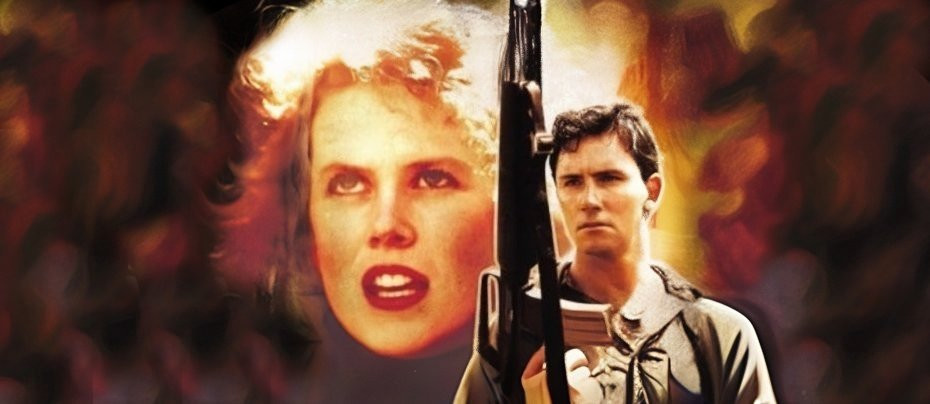

Women at War/Les Combattantes

2022 - France‘The makeup and practical effects excel at showing the full horror of some of the wounds inflicted’

Les Combattantes/Women at War review by John Winterson Richards

Following the success of their historical drama Le Bazar de la Charite, known rather crassly in English as The Bonfire of Destiny, Netflix and the French television channel TF1 got together again and decided there is no point tampering with a winning formula. So they hired the same producer, the same director, the same production designer, the same composer, the same cinematographer, the same costume designer, and the same three principal actresses, Audrey Fleurot, Camille Lou, and Julie de Bona, and commissioned another period piece.

This one is set about a generation later, in the opening days of the First World War in 1914, hence the title Les Combattantes, which Netflix translated into English as Women at War - Netflix really need to have a word with whoever decides on English titles of their foreign language productions and purchases. The Great War marks the end of La Belle Epoque, the nominal "beautiful time" of which The Bonfire of Destiny was an evocation, so there is a distinct shift in tone and Fleurot, Lou, and de Bona all play different characters - very different.

Fleurot plays a veteran prostitute who turns up looking for work at a provincial town just behind the front lines. It has to be said that she looks out place, too beautiful and too high class - she even owns and drives her own car - to be in need of a bed in a garrison bordello. There are definite hints of Mata Hari about her, especially since she knows more than she should about unit locations and seems a bit too eager to visit the front line. It turns out that she does indeed have a secret.

Lou is a trained nurse on the run from the police after a woman dies during an illegal abortion. The policeman pursuing her with Javert-like intensity is the husband of the woman who died. To be honest, Lou's character and her portrayal seem a bit anachronistic, but her overall character arc is ultimately a satisfying one.

De Bona is cast as the surprisingly young Superior of a convent which is turned into a military hospital. Dramatic convention demands that religious protagonists must either lose their faith or succumb to temptations of the flesh or both. Nuns in particular are assumed to be living in a state of overheated sexual frustration so that it only takes the sight of a man to set them off. This is a rather misogynist assumption if one comes to think of it - monks are rarely portrayed as jumping at the first woman they see - and clearly out of place in what is meant to be a feminist script, but it is the equivalent of Chekhov's gun on the wall: once the audience sees it they expect it to be fired.

These three principals are joined by a fourth, Sofia Essaidi, as the wife of the manager of his family's truck factory. He leaves her in charge of it when he goes off to War (he is a loving husband and father, so it is no spoiler to suggest what happens to him - it is all telegraphed so unsubtly that it counts as restraint that he does not have a vulture sitting on his shoulder). For some reason that is obviously more 2022 than 1914 she has an Oskar Schindler-like aversion to converting it to the manufacture of ammunition.

It is no surprise, given the personnel involved, that the strengths and weaknesses of Women at War are much the same as those in The Bonfire of Destiny, except there are signs that the team have learned a little from past mistakes. The plotting is in places - but, to be fair, only in places - laughably bad. Unlikely events abound. Character motivation frequently makes no sense. Coincidence and cliche are so common as to seem almost inevitable.

We have absurdities like President Poincaire turning up conveniently in a small town to decorate our heroines and prostitutes being allowed to wander freely around the combat zone (all right, this is the French Army, so it might be possible, but even Marshal Massena felt obliged to disguise his mistress as a dragoon when he took her on campaign). A wholly unnecessary and unbelievable subplot about a spy is particularly irritating.

Most irritating of all is the fact that these absurdities detract from some pretty solid drama with real emotional weight elsewhere in the production. There are times when the script seems to be saying some things that are quite important about war and about the role of women only to lapse into melodrama.

The war scenes are very well done. The confusion and uncertainty, the way violence can erupt suddenly out of the mundane, and the impact of casual brutality on the civilian population are conveyed very effectively by a minor skirmish in the opening episode. So is the truth that no one is safe when bullets are flying, no matter how important to the narrative they might seem. The consequences are also shown graphically, in particular how often no one has the time, or the responsibility, to tend to the wounded or bury the dead.

It is more authentic than many viewers might assume. When people today, especially in the English speaking world, visualise the Great War, the image that comes to mind is of the flat, muddy fields of Flanders and Northern France. Most know little of the campaigns in the wooded hills of Eastern France, including the Vosges, where Women at War is set. In fact, there regions saw some of the fiercest fighting of the War, especially in 1914. Graf von Moltke the Younger, Chief of the German General Staff, altered the plan he inherited from his predecessor, Field Marshal von Schlieffen, by strengthening the attack in the East at the expense of the attack in the North. This decision ultimately cost Germany the War, but only because stubborn French resistance prevented the planned breakthrough to Paris.

The pretty forest landscapes are therefore accurate, at least for 1914 before artillery flattened everything. The German writer Ernst Junger, who fought in Eastern France, describes how the cover provided by the trees was illusory: in fact it made things worse, because the roots made it difficult to dig trenches and splinters added to the injuries caused by bullets or shells. He also says the French were more likely than the British to fight to the death.

So what seems today to be patriotic posturing on the part of the French soldiers was genuine in 1914 - and, yes, they really did go into battle in those impractical uniforms, with bright red trousers and soft kepis instead of steel helmets - and, yes, they really did bayonet charge machine guns manned by well trained Germans in sensible field grey. If they were wholly incompetent, no one can deny their courage.

The production is also accurate in showing the predictable results of this reckless bravery. The make up and practical effects excel at showing the full horror of some of the wounds inflicted.

Nor does the production attempt to romanticise another horror, the squalor and exploitation of prostitution in France at the time. For all the false glamour associated with the period, La vie en rose was anything but rosy for the women in factory-like field brothels.

As in The Bonfire of Destiny, the production design, props, set dressing, and locations immerse the viewer in a wholly credible sense of time and place. Credit is due to the director for his cunning in making a relatively small number of extras look like an army and gun fights in the woods like elements of epic battles. In addition Women at War benefits from the agreeable presence of some splendid vintage cars - or, if they are replicas, very good replicas.

While producers are not supposed to think in terms of gender demographics these days, of course they do, and it is pretty clear that Women at War, was intended primarily, as the title suggests, as a "women's story" but with the War and the cars thrown in to keep their menfolk engaged. As such, it succeeds on both levels. Like The Bonfire of Destiny it is pretty heavy handed in its feminism, but at least the male characters are given greater depth and nuance this occasion, even if they are not really given time to develop.

None is portrayed as the sort of cartoon villain seen in the previous production. A particularly nasty pimp is shown as having genuine feelings for the Fleurot character, even if this is hardly a sign of great nobility and does not exactly lead to him changing for the better. The Essaidi character's odious brother-in-law finds a belated hint of courage and misplaced honour. Two other men who are initially very antagonistic to our heroines are given solid motivations and resolutions that are not unworthy of them. The always watchable Tcheky Karyo makes a General who basically represents the whole French military Establishment perhaps a bit too likeable, but he serves his purpose in the script, which is to show how the men in charge came reluctantly to value the contribution of women. It is a good point well made.

This greater sophistication in the writing carries through to the ending. Things are not wrapped up neatly. Of the three story arcs, one ends on a tragic note and three rather ambiguously but with varying degrees of optimism. After all, as we are reminded by a closing title card, 1914 was just the beginning of a four year War. This was not a time for "happily ever after."

There is little scope for a sequel but one would not be unhappy to see the same team return again for a shot at a different episode from French history. If there is still a whiff of soap about their work, it is nevertheless well acted, very well directed, and extremely well produced, and it tells important stories from a point of view mainstream history has tended to neglect.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on March 30th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.