The Spread of the Eagle

1963 - United KingdomWhen the BBC's ambitious series An Age of Kings proved to be a surprise critical and audience success in 1960, it was inevitable that the corporation would try and repeat that success by plundering more of Shakespeare's plays for translation to the small screen.

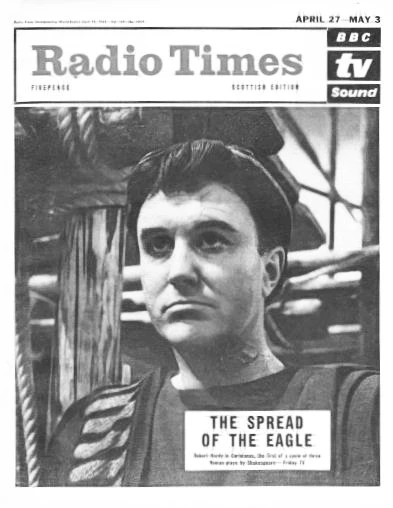

Writing in the Radio Times in April 1963, Peter Dews, the veteran BBC producer who had produced An Age of Kings, admitted that the intention was 'to present something similar.' But there was nothing similar. 'So it was decided to present Shakespeare's most 'televisible' play, Antony and Cleopatra. Before we knew where we were, we had Coriolanus and Julius Caesar, to form a Roman trilogy.'

Dews grouped all three together because he considered that they had many common features. They were all quarried by Shakespeare from Sir Thomas North's translation into English of the Greek essayist Plutarch's Parallel Lives - a series of 48 biographies of famous men. All three had characters in common and Coriolanus and Antony and Cleopatra had strong textual similarities.

'Moreover, throughout all Shakespeare's work there is a Tudor passion for order and strong government,' wrote Dews. 'In An Age of Kings, the crown of England symbolised it. In the three Roman plays, it is in the belief of Rome as an ideal, greater than its upholders or detractors, which invests every line. That ideal I have symbolised by the Roman eagle - aloof, golden, cruel. As with the English crown, we see people who try to uphold its power or destroy what it represents. We have three great personal tragedies set against a violent and dramatic political background. In Coriolanus, the honest, fearless soldier is out of his depth when he exchanges the blacks and whites of simple military conflict for the intermingling greys of politics. Coriolanus is made by and broken by Rome and finds that, though he hates Rome implacably, even he cannot bring himself to destroy it. So he prefers death. ‘

In Julius Caesar, the moderates who start the revolution are unable to stop it. Good men who murder for the highest motives are destroyed by what they unchain. ‘The conspirators murder their dictator, only to find that all they have killed is Caesar's person and not Caesarism. In the end, the spirit of Caesar, in the persons of Mark Antony and Octavius Caesar, defeats and kills them.’ In Antony and Cleopatra, we see what happens when Mark Antony opts out of his responsibilities to Rome and prefers the arms of Cleopatra to the duties of ruler of a third of the world. ‘The couple evade public responsibilities to fulfil private desires.' The themes are as topical today as ever.

Whereas An Age of Kings took fifteen weeks to complete, The Spread of the Eagle was shown in nine parts of 50-minute episodes with each tale, Coriolanus, Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra - in order of real-life historical events - allocated three episodes with a combined running time of around two-and-a-half hours per play.

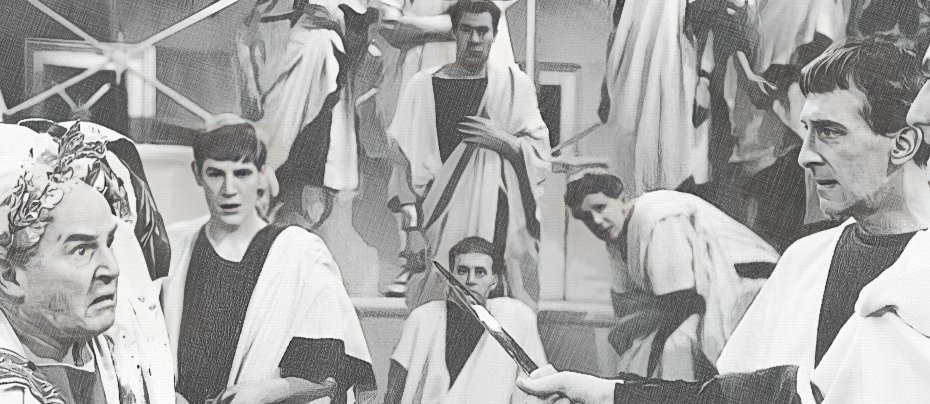

For continuity, designer Clifford Hatts built three distinctive sets: The Forum, which in Coriolanus is still being built but is large and gleaming in Julius Caesar, a massive 'marble' Senate, and the plains of Philippi, the cool cavern of a palace where the 'Serpent of the Nile' lives. In contrast to the more intimate approach favoured by later projects such as the BBC Shakespeare Collection, Hatts was asked to stress the monumental - in Dews' words, "to show great men in great places". Dews also attempted a genuine sense of scale with the cast, plus extras, at times topping the one-hundred mark.

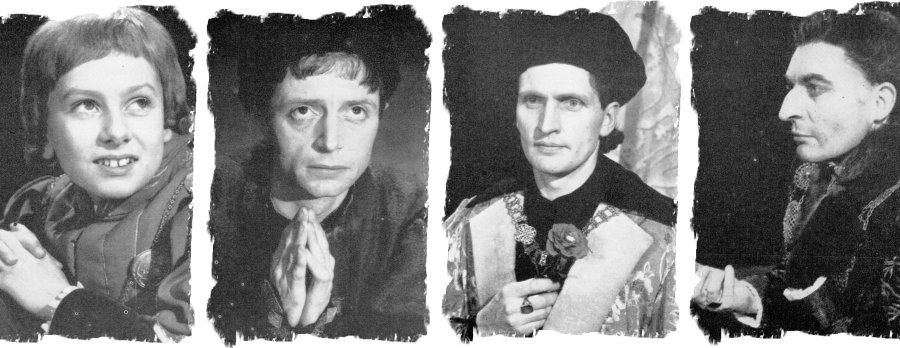

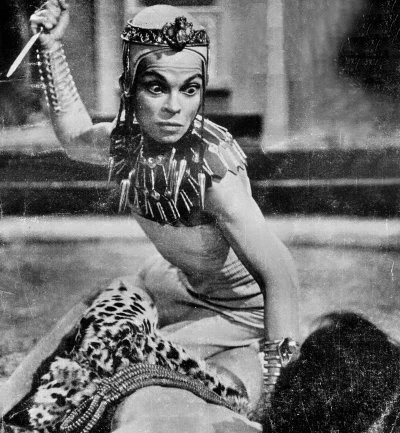

As in An Age of Kings, there was a permanent company of 20 actors, playing a wide variety of parts throughout the three plays. Keith Michell had the lion's share of the series by playing Marc Antony in the last two plays. Peter Cushing made a return to BBC drama after a number of years absence, and Roland Culver - a distinguished Shakespearean actor made his television debut as Menenius Agrippa. Beatrix Lehmann (Volumnia), Barry Johns (Julius Caesar) and Paul Eddington (Brutus) played Shakespeare on television for the first time. Quite a number of Dews' Age of Kings actors reappeared. Robert Hardy (who had played Henry V) played Coriolanus, Frank Pettingell (Falstaff) played Junius Brutus, David William (Richard II) played Octavius Caesar and Mary Morris (Queen Margaret) played Cleopatra.

Critical response to the series was very favourable. The Daily Herald’s critic Dennis Potter (yes, that Dennis Potter) wrote on 8 June 1963: ‘Shakespeare translated to the little screen can afflict the producer with immense problems of sweep and scale. But Peter Dews' current sequence, The Spread of the Eagle is beautifully accomplished in all but the battle scenes. Last night saw the completion of Julius Caesar, darkly shadowed with dissension and the pain of troubled conscience. The testy, almost juvenile quarrel and emotional reconciliation between a grieving Brutus and the sour-faced Cassius was convincingly done.

At one time, Shakespearean actors sang the words with a trembling nasal sound. But here, the camera creeps in to hold a long close-up, and a face almost whispers the poetry. Peter Cushing's Cassius, sullen and yet sad-eyed, was almost without flaw. The production fell away with the battle, but was still triumphant by any terms in which TV can be judged.’

The Stage, on 27 June 1963, wrote: ‘If that much-publicised film with Miss Taylor has half of the dramatic power of "Antony and Cleopatra" in this nine-part cycle by Peter Dews, it will be worth indulging in its spectacle. Whatever limitations cost and the television screen impose are more than offset by dynamic direction and acting of the highest calibre. In part eight, "The Alliance", Antony's fortunes reach their lowest when his judgement fails him and he loses the battle at sea. A careful and well studied performance by Keith Michell brought out the confusion and despair that the warrior feels when he sees his life in ruins and his enemies ready to come to terms with his Cleopatra. What Mary Morris may lack in beauty she more than compensates with a tempestuous and at times terrifying study of the queen of Egypt. She brings out her vanity and maliciousness and the character comes to life eloquently and with passion. The last part tomorrow should be well worth watching.’

And yet, despite the plaudits, The Spread of the Eagle failed to make an impact with the viewing public, scoring low in viewing figures and audience appreciation. Whatever elements made The Age of Kings successful, appeared to be missing in The Spread of the Eagle as far as the British public was concerned.

There are two amusing anecdotes concerning the series: On 11 July 1963, it was reported that a great many togas and centurions' outfits were left lying around the Wardrobe Department. But before the moths could get at them, they were put to good use by Jimmy Edwards and the cast of More Faces of Jim. On Friday, July 19, Jim repays his debt to this recent series of Roman plays in "A Matter of Spread- eagling".

And the other – well, on 20 May 1963 the Daily Herald printed this little anecdote:

Orchestra leader Edwin Braden was recording a musical number for the 625 Show when he looked down on a mass of cables on the studio floor and noticed that one of the 'cables' was slithering towards him. He realised it was a 2ft long snake. The band played on to the end of the number when the stage property men at the BBC Television Centre appeared and declared; "It's alright. It's one of ours. It's harmless." The snakes had been used in the play Spread of the Eagle. Mr. Braden said afterwards: "They might have told us earlier about the lost snakes. It gave us quite a shock." As a footnote, the Daily Herald reported that 'the other snake is still missing.'

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 26th, 2023. Written by Marc Saul for Television Heaven.