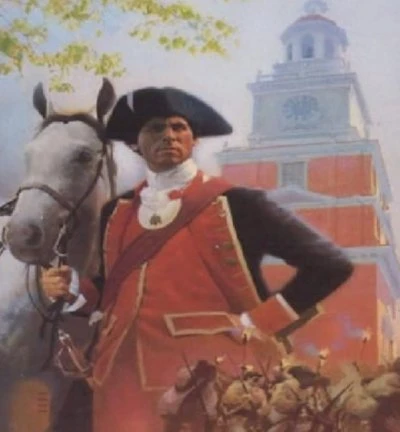

George Washington II: The Forging of a Nation

1986 - United StatesThe success of George Washington, the epic 1984 "miniseries," led to a less successful sequel, George Washington II: the Forging of A Nation on the great soldier-statesman's two terms as the First President of the United States. Since the original had covered the entirety of Washington's military career, there were no actual battles left for the sequel, and less scope for grand set pieces. This, and the fact the producers anticipated, correctly, that a bunch of politicians talking would not be so attractive to viewers, caused them to invest less lavishly in the production, even if the sequel is still a visual treat with some impressive looking scenes.

They also saved money by investing in a supporting cast that is considerably less starry. Whether this anticipation of lower ratings was self fulfilling can never be proved, but the final figures were disappointing even by the standard of relatively low expectations: the sequel attracted less than half the audience of the original.

In retrospect, it deserved better. For one thing, it actually has a more interesting story to tell. What Washington did in his Presidency defined American government, and the government of every Republic that has copied the American model, to this day. It is arguably his greatest achievement, and an even greater contribution to the establishment of the United States than his military success in keeping the rebellion alive against the odds until France, Spain, and the Netherlands joined the rebellious Colonists in the War against the United Kingdom.

The sequel's greatest mistake is its failure to show the scale of the challenge Washington faced when he was first "elected" (or rather acclaimed) President in 1789. At that point there was nothing inevitable about the United States. On the contrary, most serious political theorists of the time thought it unlikely that a Republic could rule a large territory and survive as a Republic. There were other Republics, such as Venice and Genoa, and there had been many more further back in history, but these were mostly city-states. Larger Republics were usually loose confederations, like Switzerland and the United Netherlands.

Every well educated American knew the Classics, and the precedent of the Fall of the Roman Republic was never far from his mind. Even the less educated were aware of a more recent precedent, how the abolition of the Monarchy in England just over a century before had led to chaos, then to a military dictatorship, and then to Restoration of the Monarchy. France, Haiti, and most of Latin America were to see similar patterns in the very near future.

At first the newly independent Colonies seemed to be going the same way. They had entered the chaotic phase while the War of Independence was still being fought, and immediately after the Peace it looked as if they would either implode due to internal disputes or be picked off by external enemies. Seasoned political observers such as Frederick the Great anticipated that they would eventually be reaffiliated in some way with the United Kingdom. Some serious people in America saw their own Monarchy as the only way to preserve their independence, while many others feared it. The script of GWII - its long title may have been another factor in its failure - has Washington say that the number of Americans who wanted a monarchy could be counted on the fingers of one hand. That was far from the case. That an American Monarchy was a serious proposition is evidenced by the clauses in the US Constitution forbidding anyone not born a citizen becoming President and setting a lower age limit for the office: both were deliberately anti-monarchist measures.

That Constitution was a product of a convention called to address the chaos. Washington himself was in the chair. Although the popular image of Washington as man who would rather have been enjoying the standard rural pursuits of a country gentleman on his estate is almost certainly true, the "reluctant politician" is rather oversold in GWII. Washington was in fact an elected member of the Virginia House of Burgesses for many years, and one of its delegates to the Continental Congress, before the War of Independence. The convention designed the role of the Presidency with Washington specifically in mind. He was "elected" practically unopposed. If it seems rather contrived that in GWII he is later told, almost casually, that he has been re-elected unanimously, well, that happened too. Things were very different then.

Indeed, GWII has to exaggerate the opposition to Washington in order to maintain dramatic tension. In spite of periods of relative unpopularity, his authority was never really questioned. He could easily have been President-for-Life if he wanted, perhaps even King, but his last and greatest contribution to the Republican form of government was handing over power to his elected successor after two terms.

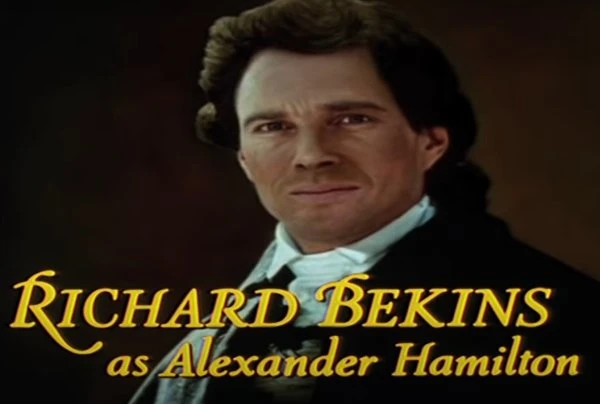

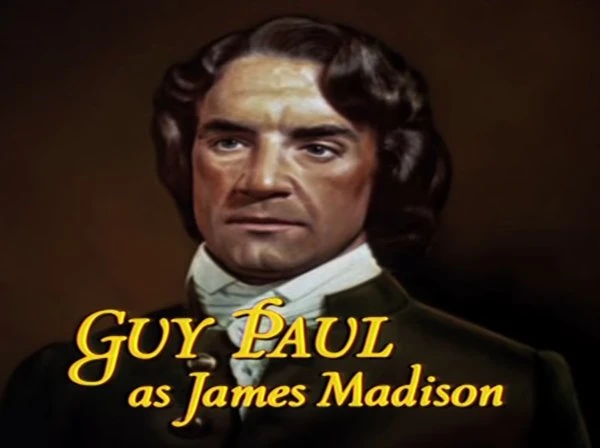

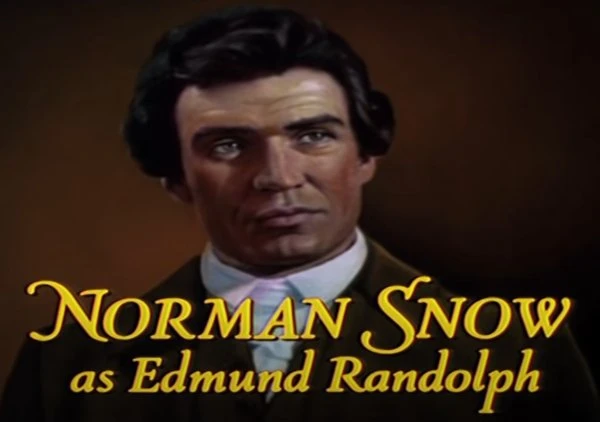

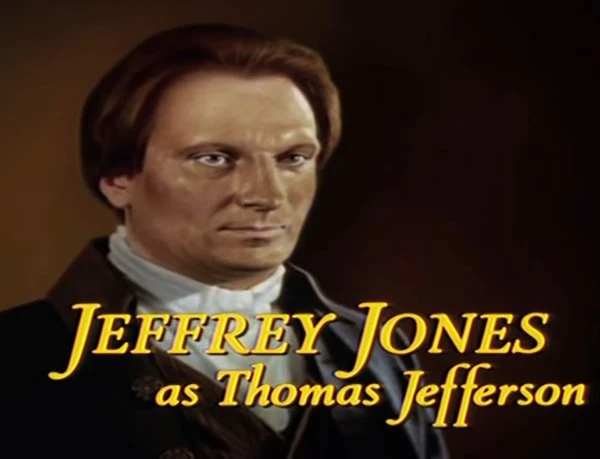

Things were also very different then in that his Cabinet consisted of only four men, but they were all men of extraordinary talent: Thomas Jefferson; Secretary of State; Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury; Henry Knox, Secretary of War; and Edmund Randolph, Attorney General. Significantly, Jefferson and Randolph both came from Washington's own home state of Virginia, while Hamilton and Knox had been two of Washington's closest comrades in arms during the War of Independence - in which Hamilton had been his ADC and Knox his artillery commander.

Yet even in this tight knit group, there was a deep division. Hamilton, one of the driving forces behind the US Constitution, wanted to build a modern, centralised, industrial state, while Jefferson, who had not contributed to the Constitution because he had been in France as Ambassador at the time, feared the effect of such a state on the inalienable liberties he had proposed in the Declaration of Independence of 1776. That fundamental division continues in American politics to this day.

Washington sought compromise, trying to chart a middle course. He hated the idea of political parties, despite being himself in effect the leader of the Federalist party that supported the Constitution, and warned all too presciently of their negative effects on the political culture of the Republic. Although the Constitution gave the President the potential to assume powers which many a Monarch might envy, Washington used them moderately, and most of his successors have therefore felt obliged to copy his example.

GWII dramatizes this through the great domestic and foreign policy debates of the time, respectively Hamilton's establishment of national credit and the American reaction to the French Revolution. The script takes a fair minded position on both. It shows the corruption that resulted from Hamilton's measures, but balances it by showing Jefferson as rather naïve in his attitude to French Revolutionaries whose view of liberty turned out to be very different from his own.

While all this is great fun for those with an interest in constitutional history, there is still very little action in the production. In an effort to counter this, we are shown a bit of the "Whiskey Rebellion," sic, even if this is no more than a brief skirmish and a rather farcical "friendly fire" incident. The whole thing was something of a storm in a teacup, so to speak, and is notable only for the irony of George Washington finding himself in the position of George III in response to a rebellion against a tax that was perceived as unfair by many. Washington dealt with the problem very easily through an overwhelming show of force, followed by mercy and conciliation - prompting the thought that history might have been very different if George III or his Ministers had followed a similar policy in the early 1770s.

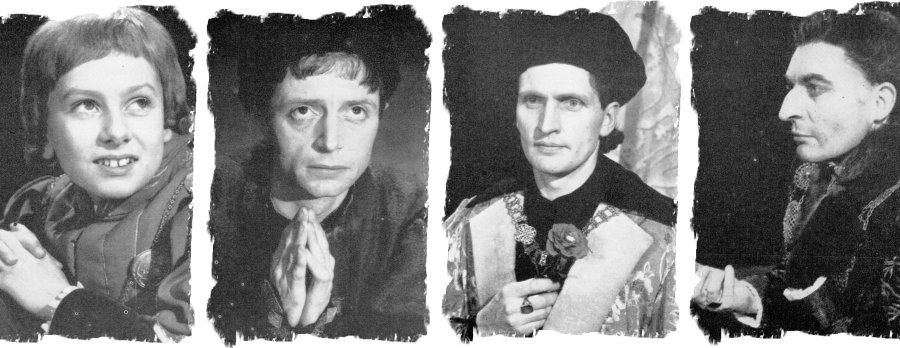

Barry Bostwick and Patty Duke reprise their roles as George and Martha Washington. Bostwick gives us a genial father figure who probably has more in common with his Mayor in Spin City than with the actual Washington. Farnham Scott returns as Henry Knox. Otherwise, the cast of the sequel has no principals in common with George Washington, except Richard Fancy, who played rabble rouser Sam Adams in the original, turns up as Hamilton's corrupt Assistant, William Duer. There may be a message there somewhere.

The most interesting addition to the cast is the talented but flawed Jeffrey Jones as the talented but flawed Thomas Jefferson. Jones is a fascinating actor in the right role and here he may come as close as we are likely to get to an authentic portrait of Jefferson's enigmatic, rather contradictory character. He is obviously very intelligent and firm in his principles, but there is an insecurity not far beneath the surface that suggests that this is not a reliable man. This may be a fair reflection of Jefferson, in whom it is difficult to reconcile the man who wrote so sincerely about "unalienable rights... (to) life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" with the aristocrat whose political career was funded by the unpaid labour of black slaves, and who was in effect a rapist (although he was probably very polite about it, no slave woman was in a position to refuse consent to a master with the power to torture or sell her and her entire family).

Most of Jefferson's leading supporters were also slave owners, as, of course, was Washington himself. GWII's attempts to paint Washington as an indulgent master with growing doubts about slavery - which were real - have not aged well, to put it mildly. They exacerbate rather than excuse the fact that he continued to force his slaves to work for him.

Like its predecessor, GWII is a triumph of good production values, even if the scale is smaller. It looks like a well made costume drama, but is lifted above that level by an intelligent conflict of ideas. It is perhaps unfair to compare it with the original, which was more of an adventure story. On its own terms, GWII is therefore a dramatic success, even if the HBO John Adams has since covered much of the same ground more effectively.

John Winterson Richards

John Winterson Richards is the author of the 'Xenophobe's Guide to the Welsh' and the 'Bluffer's Guide to Small Business,' both of which have been reprinted more than twenty times in English and translated into several other languages. He was editor of the latest Bluffer's Guide to Management and, as a freelance writer, has had over 500 commissioned articles published.

He is also the author of ‘How to Build Your Own Pyramid: A Practical Guide to Organisational Structures' and co-author of 'The Context of Christ: the History and Politics of Rome and Judea, 100 BC - 33 AD,' as well as the author of several novels under the name Charles Cromwell, all of which can be downloaded from Amazon. John has also written over 100 reviews for Television Heaven.

John's Website can be found at John Winterson Richards

Books by John Winterson Richards:

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on March 20th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.