Nuremberg

2000 - Canada United StatesReview: John Winterson Richards

At the end of the Second World War there was general agreement that the surviving members of Germany's National Socialist regime should be held to account. Churchill, raised in the brisk tradition of the British Empire, was all for shooting a few ringleaders, while Stalin, equally true to his own tradition, wanted a wholesale purge. The Americans, however, are a legalistic people, and, in the name of due process, insisted on a series of full dress trials at Nuremberg, the city where the National Socialists had held their epic rallies in the 1930s.

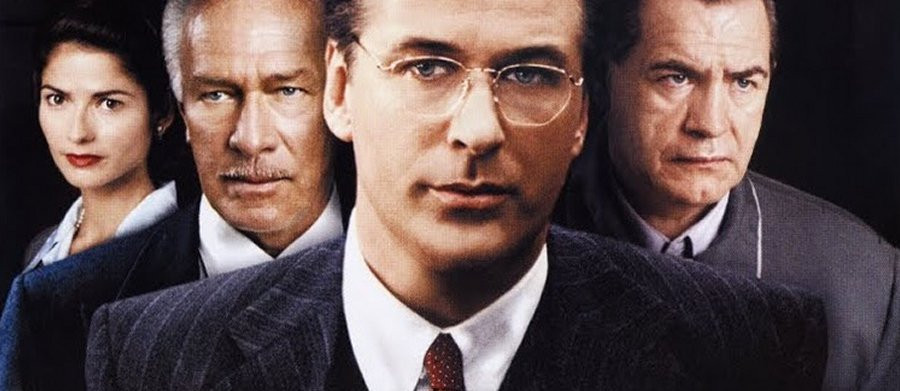

Since the result of the trials, before a Military Tribunal of the victorious Allied Powers, was a foregone conclusion, they were, like the rallies, a show intended to make a political point. The same can be said of Nuremberg, a later "miniseries" based on the first and most important of the trials, starring Alec Baldwin as the Chief Prosecutor, US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson. Baldwin, who was also an executive producer on the project, is outspoken in his personal politics, and obviously looks on his fellow Democrat Jackson as a heroic figure.

This brings us immediately to the first of several challenges in dramatising something like the Nuremberg Trials which 'Nuremberg' never really overcame. This is the ethical question of whether, or to what extent, one can or should adapt very serious and important historical facts as entertainment. There are moments when 'Nuremberg' lapses into what can only be described as melodrama.

Then there is the structural challenge. The court room drama is a well developed form, but it depends on tension and suspense - and there can be none where the result was never really in doubt.

An alternative approach might have been to present a clash of ideas as the heart of the drama, and there is certainly scope for that. Although the verdicts and sentences at Nuremberg were basically just (there are respectable legal and historical authorities who might argue that Albert Speer should have been hanged and Alfred Jodl spared rather than the other way around as happened), many jurists remain uncomfortable about the process.

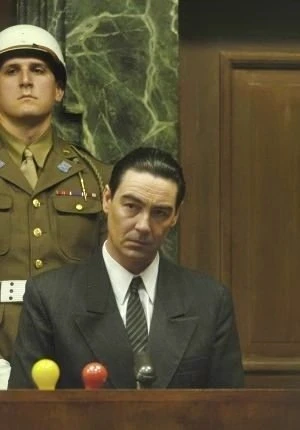

The problem for the prosecutors was that the National Socialists in power had usually been fairly careful about keeping within the letter of German law - which, of course, they controlled. Of the illegality of the Shoah itself, the deliberate and systematic extermination of millions of Jews, there was no doubt. Such was the enormity of the horror that the National Socialists themselves had tried to distance themselves from it and they had not had the courage to own their actions by publicly passing laws to authorise them. One of the few who subsequently admitted his involvement was the Commandant of Auschwitz Rudolf Hoess (not to be confused with Rudolf Hess, the eccentric sometime Deputy Fuhrer and one of the defendants at Nuremberg): played to chilling effect by Colm Feore in 'Nuremberg,' Hoess was completely matter of fact about his own crimes, apparently under the impression that, in obeying orders, he had done no wrong.

This ought to have been enough to wrap everything up, had it not been the fact that practically everyone above Hoess in the direct chain of command - Eichmann, Heydrich, Himmler, Bormann, up to Hitler himself - was dead or missing.

There was also no doubt that a number of other specific war crimes had been committed in contravention of the Hague and Geneva Conventions, but the top National Socialists seem to have gone to great lengths to insulate themselves from them and maintain their "deniability."

Jackson and his fellow prosecutors tried to get around that essentially by making up entirely new "crimes against peace" and "crimes against humanity." This upset many who thought the whole point of the trials was to maintain the rule of law. Jackson's superior on the US Supreme Court, Chief Justice Harlan Stone, was particularly scathing, comparing the trials to "a high -grade lynching party." Others felt it was hardly a universal standard of law if the Allied Powers sitting in judgement on the National Socialists were themselves guilty of some of the same offences. After all, France and the United Kingdom still had massive Empires established by conquest, the United States still had legal racial discrimination and had recently interned thousands without trial solely on the basis of race, and the presence of the Soviet Union on the Bench was a total embarrassment - Hitler did very little which Stalin had not done first. The Soviets even tried to include the "Katyn Massacre,' the mass murder of thousands of Polish officers, which everyone knew they had carried out, in the charges against the Germans.

Although there a couple of moments when a minor character mentions possible concerns about the process, 'Nuremberg' steers clear of real debate on the subject. It is simply taken for granted that the trials are a good thing because they were supposed to help secure peace. Even so, any fair minded viewer with a working knowledge of the history of human conflict - which has continued in spite of Nuremberg - since 1945 might perhaps wonder if there was not at least some substance to Hermann Goering's complaint that it was "victor's justice."

Mention of Goering brings us to the final challenge of adapting the Nuremberg Trials for television. There is a danger that any dramatisation might turn into the Hermann Goering Show.

To a great extent that is what happened at the actual trial. Indeed, it had originally been the intent. With Hitler, Himmler, and Goebbels dead by their own hands, Goering was the star defendant, the living personification of National Socialism. His moral and intellectual humiliation before the Tribunal, followed by his legal execution, were to represent the final triumph of the values of the Allied Powers. Things did not quite work out like that.

Goering would probably be diagnosed today as a high functioning psychopath. Apart from an odd sentimental streak that is surprisingly common among psychopaths, he had an almost complete lack of sympathy for other human beings - despite which he had an extraordinary ability to charm them. This made him almost unique among the leading National Socialists, who were in general a charmless bunch, and it was of crucial importance in their seizure of power. The conservative German political, military, and business Establishment had nothing but contempt for the vulgar National Socialists and disliked their Socialism. However, the aristocracy viewed Goering as - just about - one of their own, and he persuaded them to co-operate with Hitler on the tragically mistaken assumption that they could control him.

As President of the Reichstag, and later in multiple posts, Goering then played a leading role in the consolidation of National Socialist power that followed and supervised the building of the feared Luftwaffe from practically nothing. He was probably the only National Socialist leader other than Hitler who enjoyed genuine widespread popularity in his own right and would probably have succeeded Hitler in the happy event of the Fuhrer dying suddenly. However, the coming of War revealed his limitations. The performance of the Luftwaffe did not live up to his vain boasting and he fell from Hitler's favour. A recovering drug addict, he had a total relapse, and at the same time gave in to his natural propensities towards gluttony and sloth.

Ironically, it was his capture by the Americans that enabled him to recover his health: he was forced to go "cold turkey," and the Commandant of the Nuremberg prison, Colonel Andrus, played by Michael Ironside in 'Nuremberg,' put him on a strict diet. As a result, he cut a rather impressive figure in court: in a famous photograph, he looks more like a ruler at his desk than a defendant in the witness box. He also recovered his powers of manipulation - and, as 'Nuremberg' shows, even some of guards were not immune. He knew from the start that he was going to be executed but a lack of physical courage was never among his many vices: as an air ace in the First World War, he had won the Iron Cross and the 'Pour le Merite,' the famous "Blue Max," and had been selected to succeed Manfred von Richthofen in command of the "Flying Circus" after the "Red Baron" was killed in action. At Nuremberg, he set out deliberately to rebrand himself as the great "martyr" of National Socialism.

Jackson was simply not prepared for this, and it is generally accepted that Goering knocked him all over the court room during his cross-examination. This is shown fairly in 'Nuremberg,' its effect accentuated by the casting of arguably the best actor in the principal cast, Brian Cox, as Goering. Although there is little physical resemblance between the two, Cox captures with complete credibility the combination of bullying and superficial good humour that made Goering such a successful politician.

Of course, 'Nuremberg' could not leave its executive producer lying on the floor there, so the script grants Jackson a victory over Goering in a subsequent session. This never happened. The truth is that it was the British King's Counsel Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, later Lord Chancellor and Earl of Kilmuir, played in 'Nuremberg' by Christopher Plummer, who managed to pin Goering down on specific war crimes, including the murder of fifty prisoners of war involved in the "Great Escape" (for which Goering was not in fact directly responsible, but his ego did not allow him to admit that he was so out of the loop with Hitler at that point).

This is only the most irritating of many irritating inaccuracies in 'Nuremberg.' A full list would be too long. This might matter less in a historical drama on another subject, but the viewer surely has the right to expect total accuracy on such an important and still controversial topic.

Yet 'Nuremberg' gets some things right. It was one of the first representations that showed how Albert Speer's shameless toadying to the Tribunal enabled him literally to get away with murder. The trend of scholarship since then has undermined the image that Speer crafted so carefully, as "the good Nazi," that saved his neck and even allowed him to become something of an elder statesman in his later years. He was in reality one of the most culpable of the defendants, but he played very cleverly to the Tribunal's need for legitimacy and they were not ungrateful.

More importantly, 'Nuremberg' is, like the trial itself, worthwhile because it provides a platform for the eyewitness testimony of the true crimes of National Socialism, even showing the harrowing original film of the liberation of the Death Camps. This cannot be repeated too frequently. It has more emotional power than any melodrama and the inaccuracies elsewhere in the script should not be used as an excuse to deny the truth of what happened.

Written on the 75th Anniversary of the official start of the Nuremberg Trials.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 24th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.