Chiefs

1983 - United StatesA particularly classy example of an American miniseries of the format's Golden Age of the late Seventies and Eighties, Chiefs is distinguished by the presence of a full ranking A-List film star, Charlton Heston, in a principal role, not just a cameo, and by a willingness to engage in some pretty heavy issues while remaining thoroughly compelling.

Review by John Winterson Richards

Based on the debut novel by Stuart Woods, which was prompted by his discovery that his grandfather was a Chief of Police who died in the line of duty, the spine of the story is the intermittent investigation of a serial killer by three Chiefs of Police in a growing Southern town over four decades. The State in which it is located is not named, but it is clearly Georgia, which was specified in the novel, despite the main location for filming being in South Carolina.

Although the murder aspect of the plot provides the pretext for some fine suspense, there is no real mystery, the prime suspect being telegraphed quite obviously in the dialogue of the first substantial scene. The main point of interest is the social drama, the vivid portrait of a developing community, with the extra dimension of the fundamental shift in race relations in the American South between the mid Twenties and the early Sixties.

Heston plays Hugh Holmes, a banker who serves as Chairman of the City Council and goes on to become an influential State Senator. At first glance, he seems to be a typically noble Charlton Heston character, a benevolent City Father, but look closely and there are hints of a subtext. Although elections are important events in the story, the script is subversive in showing how real power resides in informal networks behind the complicated official structures. Holmes is very much the local boss and when he offers a young man support in an election, the latter tells his wife immediately afterwards that he has just been elected because he has secured the only vote that counts. Holmes also combines helping people into office with selling them houses owned by his bank. One suspects they would be well advised not to haggle about the price.

Holmes is shown as a pragmatist on racial politics. A natural conservative, despite being a Democrat, as nearly all elected officials were in the South during Segregation, he seems to accept change as a regrettable necessity. The irony here is that Heston, remembered more these days for his conservative politics in later life, risked his career as a rising young star by being very active in support of Civil Rights for black people long before it became fashionable in Hollywood to be so: he marched with Dr Martin Luther King and once picketed a segregated cinema where one of his own films, El Cid, was showing.

The Civil Rights Act had been passed less than twenty years when Chiefs was made, and there is an authenticity in the script and the production that would not be allowed on network television if it was being produced today. At the most obvious level, it may be a sign of progress that the language which was accurate for the time and place is now quite shocking to the ear, even if it may also be a sign that we still have far to go that dramatic realism has become harder to attain in our current environment. On a deeper level, writers are now more likely to signal their virtue by inserting their own disapproval of something like racism into the script, rather than let the facts speak for themselves, as Chiefs does, which is actually more effective.

Here we are presented with the reality of literally State sponsored racism on both the grand scale and the petty. At one extreme, we are shown why a black man, especially one considered a "troublemaker," had every reason to fear being picked up by the local Police under the colour of their official duties. The events in Chiefs are fictional but what happens in one case and nearly happens in another is based on a number of similar incidents in real life. Yet in many ways it is the petty everyday racism that leaves the viewer, or at least this reviewer, bubbling with anger at the knowledge that such things were normal in living memory. In one telling scene, a white boy shoots the windows out of a black church building, but the congregation can do nothing to stop him until the white policeman arrives - not because they are afraid of the boy but because they know what will happen to a black man who lays hands on a white boy even under such circumstances.

The impressive thing is that this is never explained. It does not have to be. By this stage the status of black people has been made very clear. A recent production would doubtless have them rising up to assert themselves. That would be missing the point. The worst aspect of the racism of the Segregated South was the sense of hopelessness and of its own normality that it imposed. The despairing resignation of a murder victim's father is almost as upsetting as the murder. There are no ostentatious "Whites Only" signs on display. They are not needed.

Change does come in Chiefs, but there is no sudden Jubilee in which the black people are all liberated. When a black Chief of Police is eventually appointed - several years before the first black Sheriff in the South since Reconstruction was elected in real life - he finds he still has to tread very carefully, a bit like an unfunny version of Blazing Saddles.

The cautious trailblazer is played by Billy Dee Williams, then fresh off The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. He gets to do a lot more here and his performance makes one wonder why he did not find more leading roles like this, but it is another reminder of how Segregation was only recent history then that Hollywood was still reluctant to have black actors front major projects, with even the well established Sidney Poitier concentrating more on directing.

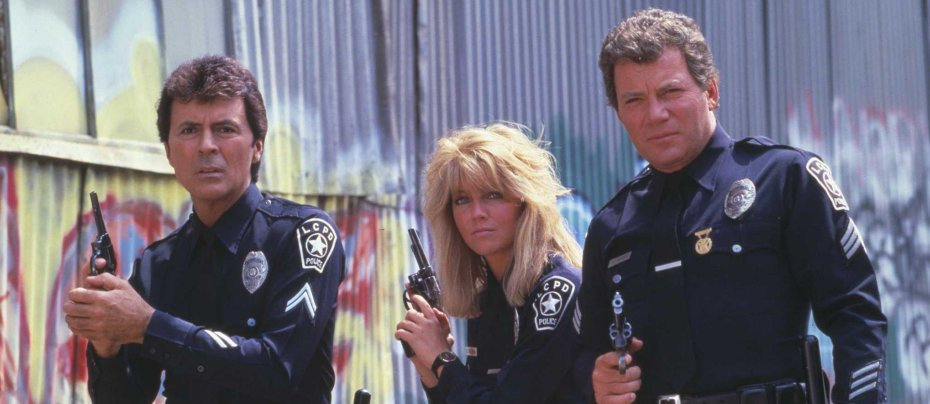

Keith Carradine deserved his Emmy nomination as the reclusive former soldier who fancies the idea of becoming the town's first Chief of Police. The job is - wisely - given instead to thoroughly decent Wayne Rogers from M*A*S*H. The beautiful Tess Harper (Tender Mercies, Breaking Bad) plays his wife. Stephen Collins plays their son as an adult and Victoria Tennant (The Winds of War, LA Story) his British war bride, an incongruous presence in a claustrophobic Southern drama but she does get a very satisfying scene in which she humiliates a gang of thugs in white sheets. The talented but troubled Brad Davis puts his edginess to good use as a subsequent Chief. Paul Sorvino drops his New York accent to superb effect as a menacing Sheriff. Look out for familiar character actors Lane Smith and Leon Rippy as a particularly unpleasant racist and a sycophantic cop respectively. A young John Goodman is a more flexible policeman and Danny Glover, just before his big breakthrough in films, is a black mechanic with the dangerous temerity to be better at his job than his white competitor.

The production and set designers also deserved their Emmy nomination for Art Direction. Their visual summary of the incredible changes in a rural community from the Twenties, when it is distinguished from the more developed towns presented in Westerns set towards the end of the 19th Century only by the presence of automobiles, to the Sixties, when it differs from the sort of American cities familiar today only in the type of automobiles and some other details, is brilliant. The opening titles sequence is particularly well done.

Rewatching Chiefs for the first time in forty years - twice the time that separated the production from the end of Segregation - the drama holds up remarkably well and the sense of injustice it evokes is as strong as ever. If the happy ending seems a little contrived - the novel apparently concludes with the implication that Holmes dies when he sees his whole life's work in ruins - the final scene still has an emotional punch. It is worth watching just for that.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 23rd, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.