The Life and Times of David Lloyd George

1981 - United KingdomReview: JWR

Except perhaps in Wales, The Life and Times of David Lloyd George is best remembered as the series that really introduced Ennio Morricone's haunting tune 'Chi Mai' to the United Kingdom. It had in fact been used already in two Italian films but they had made little impact in the English speaking world. Played over a beautifully filmed scene at the river near the great statesman's childhood home, it was the perfect evocation of longing, hope, and sadness, and it really struck a chord, so to speak, reaching number two in the British "popular" music charts.

Before that, the prolific and versatile Italian composer was known in Britain mainly for his work on Spaghetti Westerns. The commercial success of 'Chi Mai' showed there was much more to his music than that, and may have contributed to his being commissioned to write the score for a major British film, 'The Mission,' which opened up a new phase of his career. There are certainly musical parallels between 'Chi Mai' and the main theme of 'The Mission.'

In Wales, the project had, and perhaps continues to have, a much broader cultural significance. The 1970s had seen the development of a distinct South Welsh identity associated with rugby, Max Boyce, the cartoonist "Gren," and the television play Grand Slam. However, this meant little to other parts of Wales, especially Welsh speaking Gwynedd, in the North, where Lloyd George is still seen as a heroic figure, or at least a local boy made good - very good.

The beginning of the 1980s was also a pivotal moment in Welsh television, with the broadcasting of most Welsh language programmes being transferred from BBC Wales to the new dedicated channel S4C. It was a good time for BBC Wales to show it was a serious player in English language broadcasting and not just in Wales. BBC Wales has in any case long been viewed within Wales as an organisation with a strong commitment to Welsh national identity - which is the polite way of saying what others might call a hotbed of nationalism. So the time was right for a prestige project with a distinctively Welsh theme that was not just about South Wales and rugby.

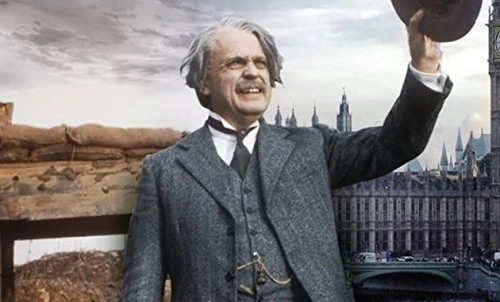

David Lloyd George was a truly remarkable man by any standards. Illegitimate, raised in relative poverty, and, of course, Welsh - English was not his first language - he rose to become Prime Minister at an unimaginably class conscious time, and led the British Empire when it was at its greatest physical extent. Along the way he founded what later became known as the "Welfare State" and established much of the modern British constitution as it exists today.

He was therefore the perfect subject for the BBC Wales project, and they did not stint on employing the talent necessary to bring him to life. In addition to paying the substantial licence fee for the music to Morricone - who was famously expensive even then - they employed three big names, Elaine Morgan as writer, A J P Taylor as historical adviser, and Philip Madoc in the title role.

Morgan was the closest Wales had at the time to what the French would call a "public intellectual." Successful in a wide range of writing genres, she was slightly eccentric in manner and in some of her opinions, such as her advocacy of the generally debunked "aquatic ape" theory. She was seen as "a funiosity" according to your reviewer's late mother, who was raised in the same South Wales Valleys town where Morgan lived (contrary to legend, it is not true that everyone in Valleys towns knows everyone else - but they know someone who does). Yet no one has ever questioned the double BAFTA winner's ability to deliver an effective script.

Taylor was one of the most fashionable academics of the 1970s, mainly because of his gift for a telling phrase and his ability to give apparently unscripted talks to camera ex tempore. It has to be said that, as a historian, he had his prejudices, and he seems to have shared with Morgan a sympathetic attitude to Lloyd George that made the project a little too reverential.

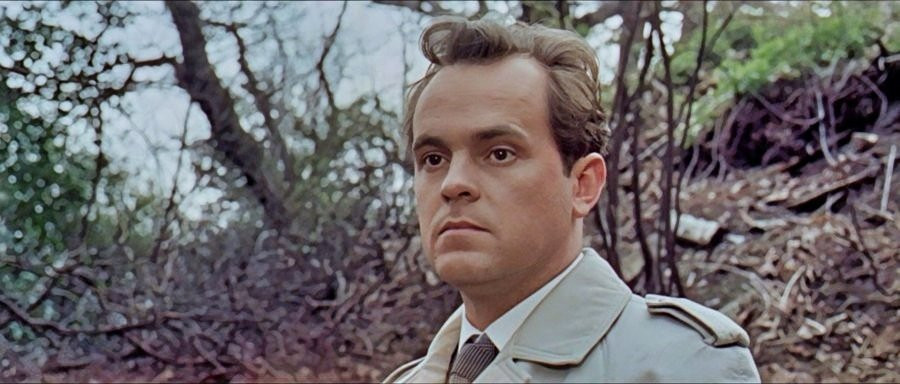

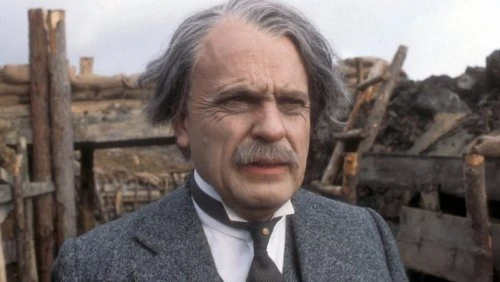

Madoc may be the definitive Welsh actor of his generation, thanks in no small part to his portrayal of Lloyd George. This is not to say he is the most famous: there have been many Welsh actors, like Richard Burton and Sir Anthony Hopkins, who gained far greater international recognition but who have little that is distinctively Welsh about their body of work. As Lloyd George, Madoc became the epitome of Wales, or at least of how the earnest type of Welshmen wanted to see themselves, and therefore the Dean of the Welsh acting profession for the rest of his life. Among many other projects, he went on to make the excellent A Mind to Kill.

He had enjoyed a good career before Lloyd George as an easily recognised villain in a wide variety of film and television projects. He made something of a speciality of German officers, most famously in what is probably the best remembered episode of Dad's Army as a U-Boat Captain who likes lists and is very fussy about how his chips are cooked.

Lloyd George was therefore the role of a lifetime and he made the most of the opportunity. In retrospect, it was the role he was born to play - except that he actually had a much better speaking voice than the historical Lloyd George, whose reputation as an orator was built more on his mastery of technique in the style of the great Welsh Nonconformist preachers.

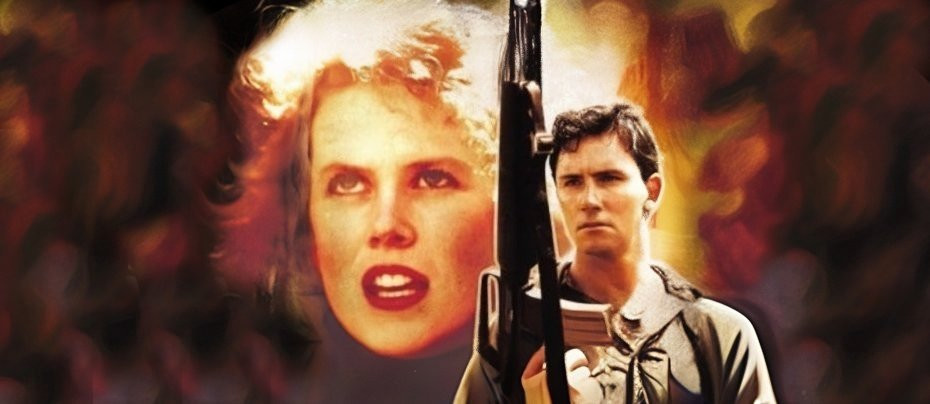

One suspects that, with a lot of the budget having gone on Morricone, Morgan, Madoc, and Taylor, there was not much left for the supporting cast. One surprisingly familiar face is an expatriate American actor who spent a lot of time in Britain, William Hootkins - best known for his brief role in 'Star Wars' as a character given the rather cruel name of Porkins.

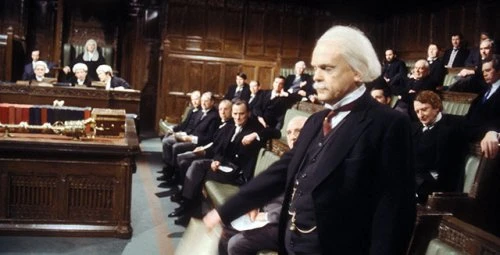

The generously built American actually does a fine job as the young Winston Churchill. The odd but apparently genuine friendship between the working class Lloyd George and the aristocratic Churchill was one of the few constants in the erratic public careers of both men. As a junior MP, Churchill seems to have been rather in awe of the magnetic Welshman and acted as his right hand man in his radical reforms. Lloyd George later showed great loyalty to Churchill, employing him when he had become something of a political liability, and was in turn rewarded with loyal and effective service. It was Churchill, the Apprentice who in the end surpassed the Master, who eventually made Lloyd George an Earl and employed his son as Home Secretary.

There are other aspects of Lloyd George's career that are not so much to his credit, and Morgan's script rather skates over them. Top of the list is the Marconi Affair, an "insider trading" scandal that, in more recent times, would certainly have ended the career of any politician who was as involved as Lloyd George was - and might well have led to criminal prosecution. Lloyd George was saved only by the kindness of the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith.

Lloyd George later showed his gratitude by intriguing tirelessly - and ultimately successfully - to take Asquith's place as Prime Minister. Britain was by then deeply engaged in the Great War, and things were being run very badly. Asquith was a very bad War Prime Minister and Lloyd George knew he would be a good one - as, indeed, he turned out to be - so it could be argued that, in a national emergency, personal obligations had to take second place to the greater good. Lloyd George certainly did argue that. Nevertheless, the whole business left a nasty taste and Lloyd George's own party, the Liberals, split irreparably over it and were subsequently destroyed as a major electoral force. They have never led a Government since. The script views this from Lloyd George's point of view, which is fair enough because the series is about Lloyd George, but it gives the whole project a hagiographic feel that is not justified by the facts.

The same is true when Lloyd George is presented as a helpless bystander as casualties mount on the Western Front, blaming Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, whom he lacks the power to remove as Commander-in-Chief. At the time of the production, the revisionist view of the Great War, that the British soldiers in the Trenches were "lions led by donkeys" - an expression popularised, perhaps surprisingly, by a future right wing Conservative MP, Alan Clark - was being treated as established fact.

Since then, military historians have in general tended to a more nuanced assessment. Many now argue that Haig was right that the Western Front was the decisive theatre of the War, and so the efforts of politicians like Lloyd George and Churchill to divert resources to other theatres may have been counterproductive. At least Haig had a strategy, even if it was not a very good one, and while Lloyd George liked to distance himself from it, he never came up with a clear and viable alternative. Even if he had, there is no possible excuse for Lloyd George's involving other senior Generals in his typical politician's intrigues against their superior officer - stirring up the ambitious and treating those who opposed him very badly. This was totally unhelpful and undermined the common purpose at a crucial time - and is also ignored by the script.

Lloyd George was still, nevertheless, a truly great man, but this means that, like all great men, including Churchill, he had great faults along with his great virtues, and, taking great risks, he had great failures along with his great successes. Morgan, Madoc, and Taylor do not really want to engage with this. They are happy to show his flaws - especially his notorious womanizing - but his political mistakes are either ignored or blamed on others. In the end, 'The Life and Times of David Lloyd George' is great drama - thanks mainly to Madoc's magisterial performance - but questionable history.

Morgan's equivalent these days, a top scriptwriter given the same commission, would probably present Lloyd George more as a loveable rogue. Neither part of that would be entirely unfair.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on July 28th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.