Masada

1981 - United StatesIt was essential to hire a prestigious cast worthy of the status of the project. The Big Name was Peter O'Toole

Review by John Winterson Richards

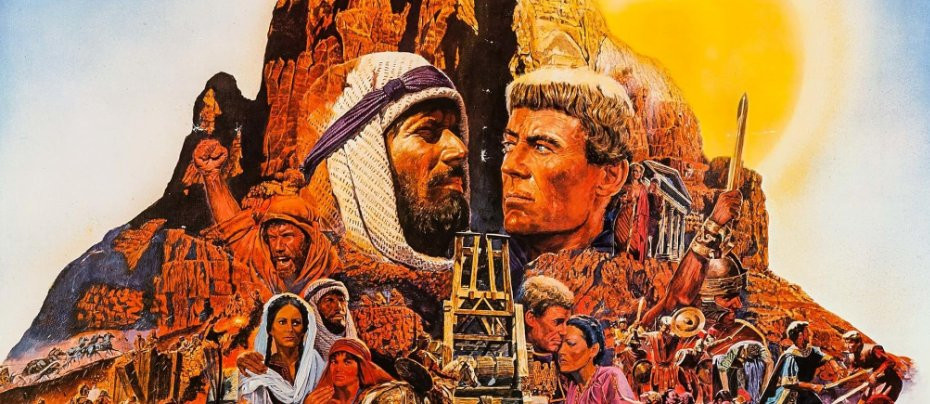

Anyone visiting the ruined fortress of Masada overlooking the Jordan Valley will understand why Herod the Great built it as a refuge for his family in case of emergency. Perched on a pillar of rock in a desert, it looks both inaccessible and impregnable. This was put to the test when his Jewish subjects rebelled against their Roman overlords seventy years after his death and Masada became the rebels' last stronghold. The Siege of Masada, which probably ended in 73 AD, has since become a symbol of Jewish resistance.

Yet Masada is also a symbol of something else - because the Romans reached the apparently inaccessible and captured the apparently impregnable. The military theorist Edwin Luttwak has explained that there was no real need for them to do so: they could simply have posted a squadron of cavalry at the nearest water source and isolated the fortress completely. They took it simply to make a point - that they could - to demonstrate to their whole Empire that there was no defying Rome. Masada is therefore a symbol of the image of unstoppable force that built the Empire as well as a memorial to the people who tried and - spoiler alert - failed to stop it.

The point is also well made in Ernest K Gann's intelligent novel The Antagonists, which uses fiction to fill in the gaps in the narrative left by the Jewish historian Josephus, our primary source for the Siege. A rebel turned collaborator, Josephus had left for Rome before the mopping up operations, including the Siege, so his description lacks the human element of some of his accounts of earlier events. Gann provides this in the form of an imaginary psychological relationship between the Roman and Jewish commanders. The miniseries adds to this by putting more emphasis on the broader political context.

The script takes us to Rome itself and implies that the Siege was crucial to the recently established Flavian regime. While this may be an exaggeration - after all it employed only one of the thirty Legions in the Roman Empire at the time - the Princeps or Emperor Vespasian certainly had a personal interest in the outcome. A professional soldier of relatively humble origins, he had been Commander-in-Chief against the Jewish rebels when the assassination of Nero triggered a massive Civil War, from which Vespasian had emerged as the eventual winner. His son Titus had succeeded him as Commander-in-Chief and broken the back of the rebellion, but there was still a widespread feeling that the new Dynasty had unfinished business with the last of the rebels.

These high stakes certainly brings an appropriate sense of the epic to the proceedings in the miniseries. So do the production values. A great deal was evidently spent on costumes, props, and sets, and on some commendable research to get most, if not necessarily all, of the details right. The great Jerry Goldsmith was hired to write the score, or at least the memorable opening theme. This set the tone of Masada being a serious production - which was perhaps necessary to achieve the most impressive thing about it...

It was filmed on location at Masada itself. It is impossible to imagine similar access being given to a site of such huge cultural and archaeological significance these days. Visiting many years later, your reviewer was astonished by the scale of what was apparently the giant ramp the Romans built to capture the fortress - imagine a hill collapsed against another hill - only to be told that at least part of it had been left there by the miniseries production. It is fair to say that, at least as late as the Seventies, there was more of a "Wild West" attitude to standards in archaeology and heritage conservation in the Holy Land than there is now.

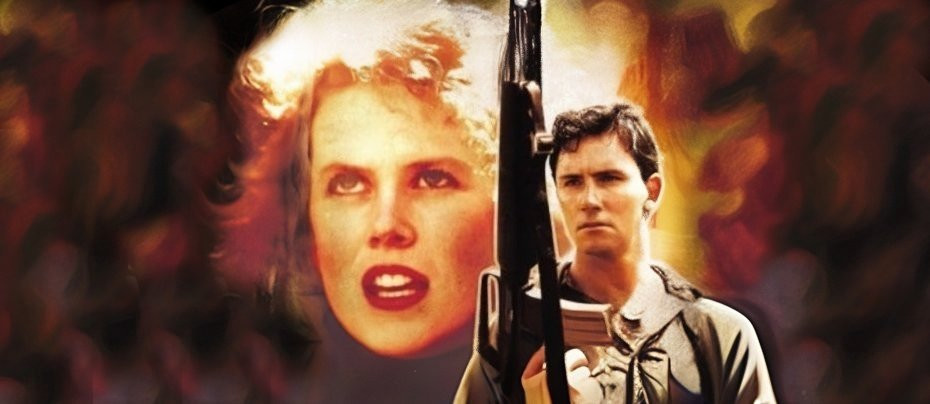

It was essential to hire a prestigious cast worthy of the status of the project. The Big Name was Peter O'Toole. Although he was at this point no longer the big box office draw he had once been, he was definitely a cinematic leading man, and getting him to play the lead in a miniseries, as opposed to a brief cameo, was a considerable achievement at a time when there was a definite class distinction between film and television actors.

On the other side of that class distinction, Peter Strauss (Rich Man, Poor Man, and later Kane & Abel) was already on his way to becoming a mainstay of classic miniseries. As was much remarked, at least in Britain, when it was first aired, the production seems to have had a deliberate policy of casting American actors as the Jewish characters, so that the American audience would relate to them and understand that they were meant to be the good guys, while the Roman characters were played by British actors, a British accent often being the telltale sign of a villain on American television. If the intention was for the viewer to identify with the rebels, 1776 style, and equate British Imperialism with Roman, things did not quite work out that way. As usual with such international casts, there was a noticeable difference between the styles of the actors of different nations - and, some might say, the general quality of their performances. Whatever the reason, the Roman characters are by far the more compelling.

O'Toole plays the Roman commander, Flavius Silva, as a war weary soldier. In fact, Silva, who seems to have been Legate of both the Province of Judaea and the Tenth Legion simultaneously, was an ambitious politician who went on to a very successful career after the Siege. Indeed, the historical Silva may have had more in common with a character played by David Warner, who turns up very inconveniently at the Siege as a sort of political commissar from Rome. Denis Quilley and Anthony Valentine (Callan) are Silva's unreliable senior officers, while Anthony Quayle (Strange Report) is his far more agreeable Chief Engineer. The interplay and conflict between these characters is actually more involving than the conflict between the Romans and the Jews.

Timothy West is well cast as the tough but amiable Vespasian (who has been played more recently by Sir Anthony Hopkins in Those About to Die) and Nigel Davenport as the man to whom he basically owed his Empire. Other faces familiar to British television viewers among the Romans include Jack Watson, Warren Clarke, Christopher Biggins, the ubiquitous Vernon Dobtcheff, the even more ubiquitous Morgan Sheppard, George Innes, Norman Rossington, Clive Francis, Michael Elphick, Nick Brimble, Ray Smith, Ken Hutchison, and Kevin McNally.

Strauss is a typically virile American hero as the rebel commander Eleazar ben Yair, the script making him more of a sympathetic family man than the ruthless fanatic that history implies he was. Joseph Wiseman (Dr No) and Paul Smith (Red Sonja) also emphasise the broad humanity of the Jews of Masada. Barbara Carrera is very attractive as Silva's conflicted concubine. Richard Basehart (Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea) provides a stately voice over.

While Masada works well as drama, it must be approached cautiously as history. Historians have identified a specific "Masada myth" that exploits the bare facts recorded by Josephus to promote a nationalist agenda and it cannot be denied that the miniseries leans into it. That might have been a factor in how the production obtained such extraordinary permission to film at a national monument. If so, there may have been an element of practical necessity to it. Either way, some historical footnotes are required: the garrison at Masada was not made up of a diverse range of ordinary refugees but mostly of hardline terrorists, and their final act was by no means entirely voluntary as the script implies. That said, neither is there any there denying their courage, or the fact that they defied an Empire and forced it to do what seemed impossible in order to bring them down.

For further reading – The Context of Christ, Young Herod, Seven Days in Jerusalem, are all available from Amazon

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 2nd, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.