The Cleopatras

1983 - United KingdomWith a long tradition of classic historical dramas to its credit, the BBC must have had high hopes when, in 1982, it commissioned Philip Mackie (the man behind ITV's The Caesars, 1968) to tackle it's third ancient-historical drama series. But following in the footsteps of the sublime I, Claudius (-via the much derided The Borgias), the corporation finally arrived at the ridiculous (according to most TV critics and viewers) with The Cleopatras.

It wasn't so much a case of television heaven as near television hell. Those that know their history will be aware that there was more than one Cleopatra, and they were not Egyptian at all-but Greek. As writer Philip Mackie told readers of the Radio Times in the week that the series started on BBC2, "Just before he died, Alexander the Great carved up his empire. His chief staff officer, Ptolemy, said -casually, by my interpretation- "I'll take Egypt." It turned out to be the richest of the Greek colonies but nobody else wanted Egypt at that time. It was too far from home." The new ruler promptly assumed the divinity of the Pharaoh's for himself, thereafter regarding his blood and that of his successors as the pure water of the Nile. In order to keep it pure-the monarchs of the Ptolemaic dynasty tended to marry the nearest relatives they could find, including their siblings and their own children, legitimate or otherwise. "They murdered each other frequently, too," explained Mackie, "which reduced their supply."

As the years rolled by and they continued to bump each other off, the women began to emerge as the dominant of the species. "They were much tougher than their uncles and brothers and fathers," continued Mackie. The last six queens, around whom the serial was built, were all called Cleopatra and were the toughest of the lot. Before Egypt succumbed to the spreading Roman Empire, the final Cleopatra manifested the deadly strengths of each of her predecessors, plus a few subtle variations of her own.

This is the Cleopatra who has intrigued writers from William Shakespeare to George Bernard Shaw and who has attracted like a magnet the leading actresses of every generation, before Elizabeth Taylor and since. "The previous Cleopatra's were content to rule over Egypt, but the last one aspired to be Queen of the World."

The Cleopatras appeared to have all the elements going for it that made I, Claudius so successful. And in Philip Mackie, a man who had already won numerous TV awards, not least for his adaptation of The Naked Civil Servant and for series such as The Organisation, they had an established writer of repute, who knew his way round a TV script with his eyes closed. Some less than charitable critics went as far as suggesting that had he adopted this method, he may well have produced better scripts.

So where did it all go wrong? Before setting out to write the TV series, Mackie spent four months on research, much of the time immersed in Bouche-Le-Clercq's classic 'Histoire des Lagides.' What grew out of all this was a serial he and producer Guy Slater, referred to as 'horror-comic' in style. This was partly because the casual horror of life under the Cleopatra's seemed to them to demand a deadpan, matter-of-fact approach: anything else, they felt, risked trivialising the events or taking the people too seriously. "The serial isn't exactly tongue-in-cheek." said Mackie. "Wry, perhaps. I've tried to make it accessible without turning it into Coronation Street. All dreadful events have a comic side, but there is no revelling in the grotesque. It's not in me to be flippant. I believe murder is a very serious business, especially for the people who get murdered."

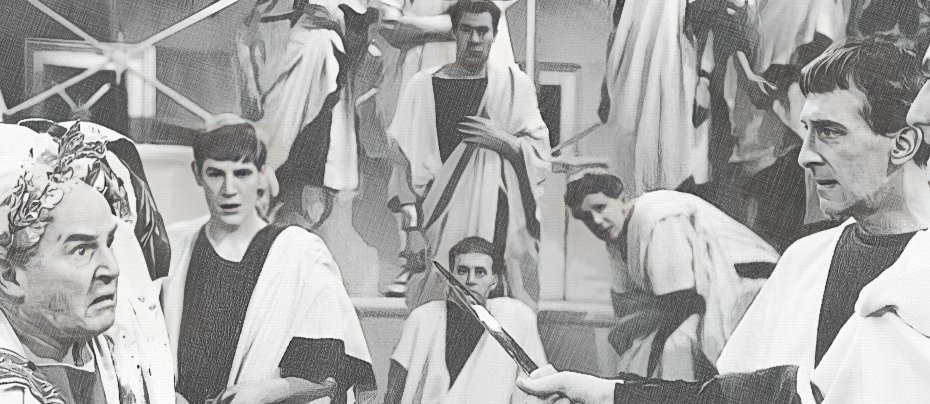

But The Cleopatras, as director of all eight episodes John Frankau pointed out, was a far cry from the costume drama that audiences at that time were used to, and the challenge was to find an overall tone and technique to match the style of writing. In the end, what he and designer Michael Young went for was what was described as a 'moving tapestry', consisting of painted interlocking pillars 20 feet high, flights of stairs and a variety of curtains to divide the space into rooms. Sets appeared to float as if, in Young's words, "painted in a void" and he did not feel the need to create a 'real' horizon beyond or a 'convincing' sky above. Authenticity was sought however, in the actors, and this involved sacrifices described as way beyond the call of duty. Those playing nobles had their heads shaved, including some of the female characters. Also, true to the custom of the time - the Egyptian palace's retinue of handmaidens were bare-chested. The Cleopatras also consumed more gallons of body make-up than the average drama serial. People at the court were painted different colours according to status, and many of them had decorative stencils made round their collarbones and on the backs of their feet. But the Egyptians did not have any body hair, and actors playing servants had to remove all theirs.

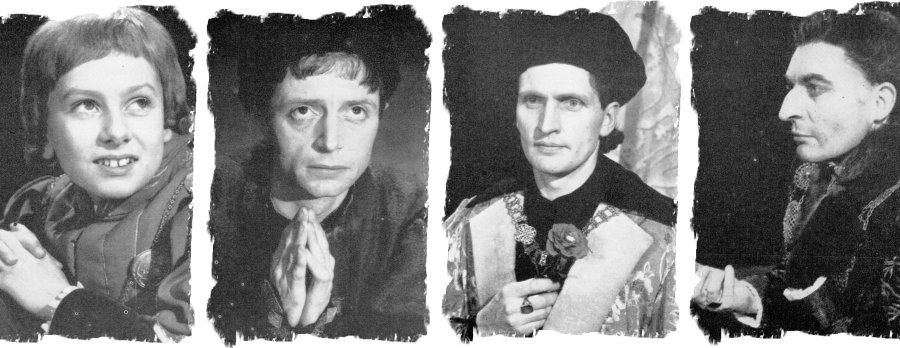

At the centre of all this was 31-year old actress Michelle Newell who played the final Cleopatra to whom the story is told in flash-back. Newland also played the last Cleopatra's great-grandmother. Six other actresses played Cleo's but only one, Amanda Boxer went so far to shave her head. Richard Griffiths played the aptly named 'Pot Belly' among whose catalogue of misdeeds were the murder of his sister's son, marriage to that sister and the subsequent dismemberment of the son they had together. Allegedly, Roy Kinnear was originally approached to play that particular role but declined the opportunity. The actors were called upon to give larger than life performances, in keeping with the outrageousness which Slater, Mackie and Frankau were determined to capture. "The Cleopatras," remarked Guy Slater, "didn't take itself seriously. It was a hard-hitting, unsentimental look at a tribe of fairly repellent people. We took dramatic licence to give the necessary verve and gusto. We didn't want the series to have a quiet domestic naturalism to it. No dead hand of realism with palm trees or shots of the Nile. Historically accurate but not reverential." It was a brave approach to take, but it seems as though a misguided one.

The series was heavily criticised and much derided at the time and may well have put the final nail in an otherwise golden era of historical BBC costume dramas. But without the benefit of a re-showing and no release as yet on video or DVD, it is hard to evaluate the series by today's standards, and it may well be that the production would find a more appreciative audience today. As such, one wonders if a modern audience would ultimately see The Cleopatras as an historical, or hysterical drama.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on December 4th, 2018. Written by Laurence Marcus (2000) for Television Heaven.