The Falklands Play

2002 - United KingdomReview: John Winterson Richards

If you want to publicise something, try to suppress it. Political drama tends to age very quickly, so The Falklands Play would probably have been generally forgotten by now had it not been the centre of a controversy about BBC bias that continues to this day. In 1983, Ian Curteis, a highly respected writer whose credits include Prince Regent and Churchill and the Generals, was commissioned personally by the Director-General of the BBC himself, Alasdair Milne - a very unusual procedure - to write a drama about the then recent Falklands War.

Curteis duly submitted his work, only to find that some of the Director-General's subordinates, including the powerful Controller of BBC1, Michael Grade, did not share their chief's commitment to the project. They criticised Curteis' script and demanded changes. To cut a very long story short, Curteis began to suspect they were motivated by political prejudices against its generally positive depiction of Margaret Thatcher and went public with his concerns. The official response was that the objections were not to the politics of the script but to its quality.

It was only in 2002 that audiences were given the opportunity to judge for themselves when an edited version of the script was finally made into a drama. It should in fairness be noted that some of the scenes not filmed, notably those set in Argentina, had been the subject of the strongest criticism from Grade and his colleagues.

It is therefore possible that those cuts made all the difference, but, either way, the production we saw left little room for criticism of the script on grounds of quality.

It is a fine piece of writing, well researched, fair minded, authentic, and pacey. Although there is little time to do more than sketch the main characters, most stand out clearly and distinctly, helped by some very strong casting. Above all it manages to maintain the tension very effectively, which is quite an achievement given that we know now how everything turned out - there was, of course, no such certainty at the time.

There is also no denying that this is one of the most favourable portrayals of Mrs Thatcher ever presented by the mainstream entertainment media. Of course, this is not saying much because most of the others have been overtly hostile. However, it may still be enough to make some one side of the political spectrum to think it deliberately biased in her favour and some on the other side to suspect them of wanting to suppress it for that reason.

Yet it is not a biased portrait. It sticks close to the facts according to the sources we have. It would seem unbalanced only to those people who would simply not accept any Margaret Thatcher who did not resemble the cartoon version in Spitting Image, and who wanted her to be a shrill, raging, bloodthirsty, war mongering megalomaniac.

The evidence suggests the opposite. By all available accounts, she was calm, methodical, and determined, and so were her principal advisers, as they are shown here. No doubt, if the same or similar events were being dramatised today, there would be lots of emoting and swearing and shouting and opportunities for ostentatious "acting." Despite what the likes of Peter Morgan tell us, one has to wonder if even today's politicians are really like that.

If so, things have changed a lot since the 1980s. Then statesmen expected to act like statesmen. Remember that at the start of the Falklands War Mrs Thatcher's Cabinet included no less than three senior Ministers who had won the Military Cross for gallantry under fire in the Second World War - Willie Whitelaw, Lord Carrington, and Francis Pym. Carrington had led the first tanks across the bridge at Nijmegen in Operation "Market Garden." Other Ministers had also served in the armed forces, if only as National Servicemen. These were experienced people in their fifties and sixties who had been trained to keep cool in a crisis, and so were the advisers around them - not at all like the youngsters to be found in Government offices these days.

Facts do not necessarily make good drama. Perhaps, for purely dramatic reasons, some over emotional youngsters might have had more market appeal than middle aged men talking calmly through the options. Yet by sticking to those facts Curteis still delivers great moments that are all the more powerful when one knows that they are true.

If Mrs Thatcher's private conversation includes some formal speeches that sound a bit much for the occasion, that is well within the established conventions of dramatisation especially since they reflect her documented public positions and personal opinions.

Curteis also establishes his honesty by taking a line that is far from uncritically pro-Thatcher. He shows how a misjudgement by the Thatcher Government itself may have led the Argentine junta to assume that Britain was not sufficiently interested in the Falklands to defend them. If the script presents Mrs Thatcher's own motivations and actions in a positive light, the same is equally true of Michael Foot, the Labour Leader of the Opposition, whose difficulties in balancing his criticism of the Government with his genuine disgust for the Argentine regime and its actions are presented sympathetically.

Indeed, Curteis tries to present all the principal players fairly and on their own terms, including General Al Haig, whose sincere attempts to prevent a full war are sometimes not appreciated as they ought to be. The inexplicable exception is Francis Pym who, whatever his private opinions, was a stout team player during the conflict: it is therefore very unlikely that he ever broke ranks in front of the Americans as is suggested here.

Perhaps the delay in the production of 'The Falklands Play' was Providential, because at least it meant that Patricia Hodge got the role of Margaret Thatcher at the moment she was ready for it. No one has ever captured the personality of the Iron Lady so convincingly - the bustling energy, the piercing eye, the razor sharp intellect, and the moments of femininity. She is far superior to certain other actresses in the role who got more critical attention but who showed little understanding of who and what Margaret Thatcher was.

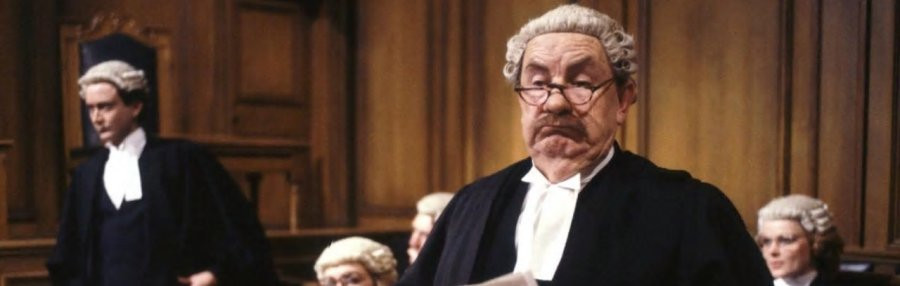

James Fox is too tall for Lord Carrington and John Standing lacks Willie Whitelaw's bulk, but both convey the essence of their respective characters perfectly. A private conversation between the two of them, old school gentlemen talking like adults, seems completely credible and is a dramatic highlight - despite which it would almost certainly be edited out these days as too undramatic. If Jeremy Child is a bit jumpy as Francis Pym, the blame lies with Pym's mischaracterisation in the script rather than with the actor's performance. Clive Merrison is spot on as John Nott, the bean counting Secretary of State for Defence who was slightly out of his depth in actual conflict.

Among the advisers, John Woodvine is, as always, a solid, reassuring presence as Admiral Lewin, the Chief of the Defence Staff, which is how the original was in the crisis. Rupert Vansittart has the same formidable demeanour as Sir Robert Armstrong, the Cabinet Secretary at the time. Robert Hardy and Jeremy Clyde are suitably urbane as a couple of Ambassadors, while the ever welcome Vernon Dobtcheff is kinder to Nicanor Costa Mendez than the Argentine junta's Minister of Foreign Affairs deserves.

The BBC therefore destroyed its own excuse: there can be no objection to 'The Falklands Play' on quality grounds. Yet it may be equally unfair to use expressions like "political censorship," not least because it is not a political work. It simply reports the facts. If the facts happen to favour Mrs Thatcher that does not necessarily make it "right wing" - except to those on the other side, many of whom work in television, to whom anything not overtly left wing is "right wing."

In any case, words like "censorship" and "banning" and "gagging" imply external intervention. This did not happen with 'The Falklands Play.' The broadcaster itself chose not to broadcast what it had commissioned, which it surely has the right to do. To say that it does not would itself be as much an external intervention as preventing it from showing what it had made.

Yet the BBC, as the BBC itself keeps reminding us, is in a special position. As a state broadcaster, financed by a tax on viewers, it is under a legal obligation to be fair and balanced. This is not the same as being apolitical. Its drama and comedy can be very political. The problem is that when the sort of people who work for the BBC mean "political" they refer exclusively to one side of the political spectrum. Writers from the other side are conspicuous by their total absence at the BBC. Curteis never had the reputation of being a political writer - in any sense or on any side. Now some brand him "right wing," not because he is but because he wrote verifiable facts about Margaret Thatcher without balancing them with uncomplimentary fictions, and because he spoke out when they were not broadcast. He has barely worked since.

Meanwhile, Michael Grade became a member of the House of Lords ...as a Conservative. Perhaps Curteis and his script were indeed victims of politics, but small-p BBC office politics rather than big-P Party politics - a classic case of subordinates trashing a project in which they had no stake because it had been imposed on them from above without consultation. Whatever the motivation, the way that the BBC hierarchy ganged up on a distinguished writer because he came to be perceived as an outsider says a lot about its inclusivity - or rather the lack of it. If the BBC cannot be held guilty of actual censorship, neither can it be called fair or balanced in this.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on August 2nd, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.