Medici Masters of Florence

2016 - Italy UkReview: John Winterson Richards

The Medici may be the most upwardly mobile family in history. In just over a century they went from being one of a number of banking houses in Florence to supreme political power there, later becoming Grand Dukes of Tuscany and marrying into the French Royal Family. In the process, they basically kickstarted the Renaissance.

This was a family who opened their huge bank ledgers with the words "In the Name of God and profit..."

Honestly, they did - historical fact - and they absolutely meant both parts. That is the key to understanding them and their spectacular ascent.

As a major prestige project, the Italian state broadcaster RAI produced three seasons of historical dramas on the crucial decades of the 15th Century which saw the Medici begin their move from commercial success to aristocracy. Since the first season was about a different generation, with a different cast and mostly different characters, and was given its own title, Medici Masters of Florence, it seems fair to treat it separately from the other two seasons, which were together titled Medici the Magnificent and which serve as a distinct sequel.

What they have in common, apart from a couple of cameo appearances of actors from the first season in the second, is a distinct visual style - which is the best thing about them.

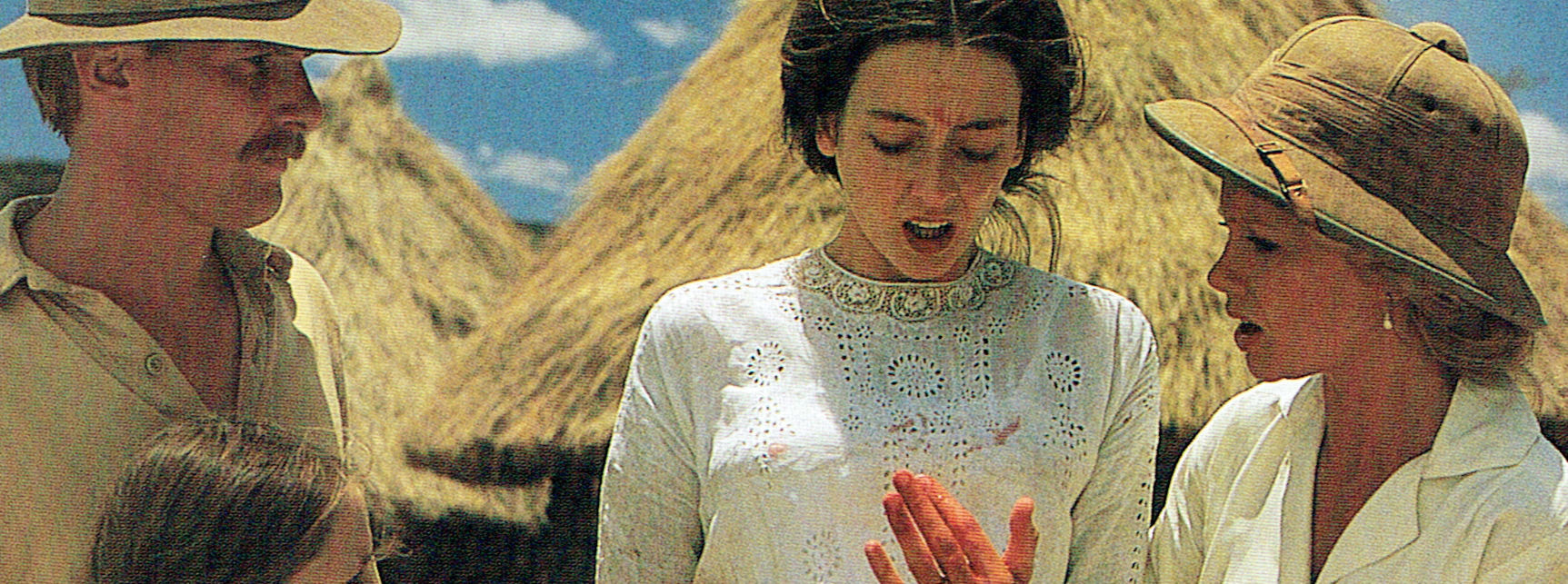

Indeed, if there is only one reason to watch either or both of the 'Medici' it is that they are two of the best looking shows ever made ...anywhere. Given the subject matter, and the fact that they were made in central Italy, this is not a great surprise. Even so, the producers deserve full credit for making the most of the superb raw material they were given.

For a start, a clever combination of CGI, sets, and location work provides a wholly credible picture of Italy as it looked in the 15th Century. One feels that historical film-making has really come of age and been transferred successfully to the small screen. The highest degree of technical skill is on display here. It will not get much better than this because there is not much need for it to do so.

On top of that, the whole thing has been photographed perfectly, especially the glorious location shots. The pastel colours of Tuscany in "the Golden Hour" are particularly evocative.

It is as if someone showed Anthony Minghella's 'The English Patient' to the whole cinematography team and said "Just go out and do this."

Quite a few of the historical events shown were filmed in the actual locations where they occurred. Sometimes this was not possible, because the original locations no longer exist or - especially in Florence and Rome - they are now such tourist traps as to make filming there impractical. In such cases, there is great ingenuity on display in finding alternative locations - having RAI on board seems to have helped in securing a high degree of access to historical sites - or in the seamless blending of sets and CGI to similar effect.

The whole thing really is a production nerd's delight to watch quite apart from the drama. Indeed, it can be enjoyed almost as much as a purely visual spectacle with the volume turned right down.

On balance, however, it is best appreciated as a drama, even if it also works well as a promotion video for the Italian tourist sector. More effort has gone into the script than in most recent historical dramas. Another of the differences between Medici Masters of Florence and Medici the Magnificent is in the quality of the writing. This may be because the former was written in part by Nicholas Meyer, the novelist whose 'Seven-Per-Cent Solution,' in which Sherlock Holmes was treated by Sigmund Freud, showed his mastery of balancing fiction and history.

Commercial reality dictates that the balance was always going to be in favour of the fiction at the expense of the history in a very expensive television production. Yet it seems that a lot of effort has gone into getting most of the historical details right in the scripts as well as in the costumes and production design. This is unusual for recent historical production to put it mildly.

It makes Medici Masters of Florencevery difficult to place on the spectrum of historical accuracy of historical dramas. It shows signs of a real effort to get into the psychology of the Medici and their rivals - and in particular that strange "God and profit" dichotomy. It engages seriously with the fact that most of them seem to have been deeply and sincerely religious, an undeniable truth that scares most modern scriptwriters.

The Medici obviously had difficulty squaring this genuine faith with some of their activities - in spite, or possibly because, of the foundation of their fortune being their provision of banking services to the Pope. At the time, the Church prohibited lending at interest to fellow Christians. Although there were ways around it, the Gospel injunction of the impossibility of serving both God and Mammon must have weighed on their consciences. In the end, they seem to have convinced themselves, like a recent Chairman of Goldman Sachs, that they were doing God's work - that, because they glorified God by using their profits to fund things like Brunelleschi's dome on Florence's Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, whatever glorified the Medici, glorified God. QED.

The Medici also had difficulty squaring an apparently sincere Republicanism with the role their wealth obliged them increasingly to assume as the uncrowned rulers of the Republic of Florence. History tells us that they eventually stopped trying and just took the crown, but the script engages intelligently with how the early Medici ran Florence while remaining "ordinary citizens," at least in their own minds.

It is therefore a pity that such a literate and well researched script takes such liberties with history elsewhere. For example, Cosimo de' Medici was not saved from execution at the last minute by his wife galloping into the Signoria on a white stallion after the arrival of his pal Francesco Sforza and his convenient army. The truth is that the canny Florentines were already well aware of the dangers of capital flight if they executed the richest man in the city. As it was, even their actual sentence of exile damaged their credit so much that they were soon begging him to come back. It seems that driving out the "super rich" does indeed make everyone poorer.

There are also annoying unforced errors like implying Lorenzo the Elder was murdered and died childless when the truth is that he died naturally and, more significantly, was the ancestor of the branch which became Grand Dukes of Tuscany.

Casting policy seems to have been to hire a job lot from Game of Thrones. Richard Madden plays Cosimo. He looks nothing like him, of course, but it was dramatic necessity to turn the rich banker into a romantic hero torn between his reluctant acceptance of his destiny to lead and a fictitious frustrated ambition to become an artist. The last is a poor substitute for seeing more of the real Cosimo's generous and hugely influential patronage of the arts. There was scope for even greater visual delights there, but instead we just get a lot of "they call me Donatello" type name dropping. It was a missed opportunity out of character with the rest of the production.

In a nice Game of Thrones in-joke, Cosimo's father-in-law is played by David Bradley. Sean Bean himself turns up later in Medici the Magnificent but in an entirely unrelated role.

It is another indication of how much money was lavished on the production that it managed to secure Dustin Hoffman, no less, as Cosimo's father, Giovanni, the founder of the dynasty. While the taboo against proper film stars damaging their brands by "lowering themselves" to do television has been dying for some time now, all too often they make it clear that they are only slumming it for the cheque. The famously professional Hoffman, by contrast, takes his part seriously and actually gives his best performance in years. His Giovanni, superficial, charming, confident in his success but unable to shake off a slight seediness, and utterly ruthless is totally credible. One can well imagine that this was how the original might have been.

A ratings hit in Italy, Medici Masters of Florence deserves its success. It also deserves to be seen more widely. The rise of the Medici, and the case study they provide in how wealth can buy political power - and how the wealthy may feel the need to buy it in order to protect their wealth - offers much food for thought in the world of Silvio Berlusconi, Donald Trump, and the oligarchs of the former Marxist Empire.

The plutocrats themselves might consider what they can learn from the Medici, who, whatever else, left a cultural legacy from which the whole world still benefits today.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 13th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.