Game of Thrones

2011 - United StatesReview - John Winterson Richards

There are a handful of television shows that become major cultural events in their own right. It has been said that Game of Thrones - or rather, more specifically, complaining about how it ended - may be one of our last great communal experiences.

The controversy about its final seasons should not obscure its great achievement, which is that it made the genre of historical fantasy, previously the almost exclusive domain of geeks and nerds, intellectually respectable in the mainstream, at least for a little while. Given that it was available initially only through subscription channels, it is probable that even more people were talking about it than watching it when it was first shown.

It achieved this because it was less of a conventional fantasy than a sophisticated modern social and political drama that happened to be set in a medieval milieu, into which the fantasy elements, including dragons and zombies, were introduced only very gradually until they seemed a perfectly natural part of their universe. There is no definite evidence that it was ever "pitched" to HBO as "The Sopranos in Middle Earth,"but, as five word summaries go, it is fairly accurate.

The television series was an adaptation of the novels of George R R Martin, who was in turn influenced by real life medieval history. The leading families of his fictional land of Westeros, the Lannisters and the Starks, are obviously the houses of Lancaster and York in the Wars of the Roses, which provide the spine of much of the early part of the story. However, the parallel is far from exact, and there are other influences, including 'Les Rois Maudits,' a cycle of novels on the early 14th Century French Royal Family - which was itself adapted as a French television drama in the 1970s.

The complicated multi-arc plot is best summarised in terms of three main strands, each represented by one of the three main characters.

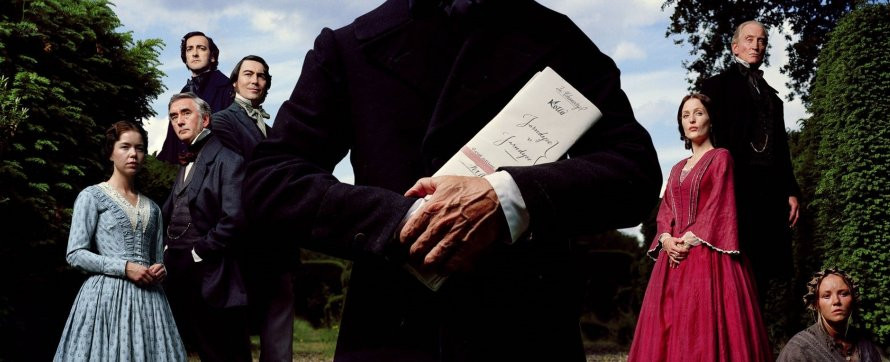

The most interesting is the high politics of Westeros, the Game of Thrones itself, played by honest nobleman Ned Stark (Sean Bean), Queen Cersei (Lena Headey), her ruthless father Tywin Lannister (Charles Dance, brilliant), and her appalling son Joffrey (Jack Gleeson), among many others. Yet amid all the great acting talent on display here, the character to watch is Tyrion Lannister (Peter Dinklage), Cersei's dissipated but humane brother, who grows from being a cynical observer of the Game to a major player in his own right.

Meanwhile, across the seas, a pretty young girl called Daenerys (Emilia Clarke), who believes herself to be the rightful Queen of Westeros, begins to build an army capable of conquering it - and rather takes her time over the whole business, despite her convenient acquisition of game-changing dragons at a fairly early stage.

Finally, there are the misadventures of Jon Snow (Kit Harington), a gormless but good looking young man who lets down everyone who relies on him, but whom everyone still loves for some reason, so they keep trusting him with ever greater responsibilities and he keeps letting them down. He even abandons his faithful pet wolf at one point. He really is very annoying.

There are numerous other sub-plots and character arcs of varying interest. The most harrowing is the prolonged destruction of the Stark family after their patriarch is killed - which, since he was played by the biggest name in the cast at the time, the guy on the poster, set the tone of the series as a story in which no character is safe. We see two young sisters, Sansa and Arya (Sophie Turner and Maisie Williams), each go through a series of ghastly experiences which leave them hardened to the point where we worry about them having become psychopaths. Their brother, Bran (Isaac Hempstead-Wright), is also drained of all emotion - and, no disrespect to the actor, gifted with the ability to do the same to every scene in which he appears.

It is generally acknowledged that the series succumbed to the Law of Diminishing Returns, possibly as early as the fourth season, and things went downhill at accelerating speed towards the end. Many, especially fans of the novels, blame the producers for departing more and more from Martin's text. In fairness, the cycle of novels is still incomplete, so events in the series began to overtake events in the novels some time ago. The producers had apparently been working to an outline of the future novels provided by Martin, but it is unclear how much they departed from it. Publishing that outline might answer as many questions as publishing the remaining novels of the cycle.

There is, however, no doubt that the producers are guilty of rushing the ending, contrary to the preferences of both Martin and HBO. The penultimate season was cut from the usual ten episodes to seven and the final season to a mere six. That spoilt everything, as characters developed carefully over the preceding seasons suddenly fell victim to mood swings in the interests of plot development. An additional episode or two in each of them might have been enough to counter most of the strongest criticisms. What seemed like illogical and inconsistent decisions might have been seen as more in line with hints dropped earlier if given more time to evolve naturally. Instead the producers decided to speed everything up, allegedly because they wanted to work on other projects.

Yet it might be worthwhile for fans to revisit those last two seasons once they have had time to get over their initial disappointment. There is still so much in them to enjoy. The epic set pieces, always one of GoT's great strengths, are particularly epic. Indeed, the production values and the acting throughout were practically faultless. If there is any justice, it has really put Northern Ireland on the map as a base for international production, and British and Irish cinema, television, and theatre in general deserve to bask in a little reflected glory for providing most of the personnel on both sides of the camera. It will be obvious to new viewers for many years to come that this was a show into which a lot of people put a lot of love, and on which they worked very, very hard.

It was only the writing that got lazy.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 17th, 2019. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.