Merlin

1998 - United StatesMerlin has become the archetype of the Wise Old Man who helps the younger hero on his journey, the direct ancestor of Gandalf and all his imitators. Although he is best known for his involvement in the hugely popular Arthurian myths, Merlin, under that and other names, has a much bigger presence in such early Welsh literature as happens to have come down to us. In some of what may be the oldest sources, it is Merlin himself who is the young hero. Sometimes he seems to be a representative of Celtic folklore in opposition to Christianity, even if it is very unlikely that Druidism survived as an organised religion as late as the 5th Century AD as some modern writers speculate. In other stories he is effectively baptised a Christian, which is hardly surprising given that Christian monks were the only ones who wrote the old tales down.

The potential of this body of literature was recognised by producers Dyson Lovell and Robert Halmi Senior of Hallmark Entertainment, who were in search of a classic story for a "miniseries" to follow up their highly successful adaptation of The Odyssey the year before. This had secured them a relatively open cheque book and they made the most of it. They invested heavily in talent, including a number of people who had worked on The Odyssey, both in front of the camera and behind it, and who therefore knew exactly what was required in this type of production.

They were rewarded with another big success - on every level, commercial, critical, dramatic, technical, and aesthetic. It pushed the boundaries of what could be done on television, and remains a masterclass on how to get the fantasy genre right.

The first stage was to put together an elite writing team. The story was devised by Edward Khmara, who had written Ladyhawke, the exquisite Medieval fantasy with Rutger Hauer. The actual "teleplay" is credited to David Stevens, who had co-written Breaker Morant, and Peter Barnes, who had written The Ruling Class. They seem to have put some serious time into research and treated their source material with respect. Between them they produced an unusually intelligent, literate, and witty script by primetime American network standards.

The story includes episodes from the traditional Arthurian romances, familiar from the literature, and from feature films including Camelot and Excalibur, both of which were obvious influences. So we get the Sword in the Stone, the Round Table, Lancelot and Guinevere, and Mordred. We also get some of the darker episodes, notably the conceptions of Arthur and Mordred. The Quest for the Holy Grail is mentioned but not really shown.

Yet what makes Merlin special is how these well-known stories are revealed as only part of a much longer struggle between Merlin and an indefinite supernatural being called "Queen Mab," self-appointed defender of "the Old Ways," implying paganism. She is not found in the ancient Welsh sources. Indeed, the first known mention of her name seems to be the passing reference in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. She appears to be a conflation of two women in Irish mythology, Queen Medb, or Maeve, of Connacht and the Morrigan.

Merlin is presented in the "miniseries" as a neutral between Christianity and "the Old Ways," committed to neither but respectful towards both - if not necessarily towards their leaders.

In the Welsh tales, Merlin is seduced and eventually trapped by a wicked sorceress named Nimue. The script subverts this rather nicely by making Nimue a Christian with an unselfish love for Merlin but who is manipulated by Mab. A lot of people are manipulated by Mab, and it has to be said that Merlin himself is not above using his influence to further his agenda against her. Vortigern, Uther Pendragon, Arthur, Morgan le Fay, Guinevere, Lancelot, and Mordred are all pawns in a bigger game between Mab and Merlin.

In the title role Sam Neill gives one of his best ever performances. It is too easy to write Neill off as "reliable," because he always is, but that word has connotations of mediocrity which definitely do not apply. He is a skilled and intelligent actor with the ability to suggest far more than he says. His Merlin combines a cynical view of human events with a genuine love of human beings. He likes to appear cool and detached but a passion for justice, as he sees it, sometimes betrays him. There is an element of bluff to his powers and he turns out to be all too fallible.

Miranda Richardson tears into the role of Queen Mab without restraint. Like several others in the cast, she seems to be really enjoying herself and that makes her entertaining company for the viewer too. While the script gives her a reasonable point of view, Richardson goes full villain. Yet there are moments when even she seems to care. She likes being Mordred's favourite "aunt" and she is the only one who shows any sympathy for Vortigern. Richardson also plays Mab's supposedly "good" sister, the Lady of the Lake, who just happens to make a couple of "mistakes" that have significant consequences. Perhaps the point is that the bad are never wholly bad and the good are never wholly good.

Helena Bonham Carter has fun as well, playing Arthur's resentful half-sister, Morgan le Fay. Until this point, her career had consisted mainly of traditional "English rose" parts, so the opportunity to play a more eccentric character led on her a new path - one she has often travelled since to good effect. Although Morgan collaborates in some dirty deeds, the viewer cannot help feeling sorry for her, and her odd relationship with Mab's gnome, Frik, is ultimately very poignant.

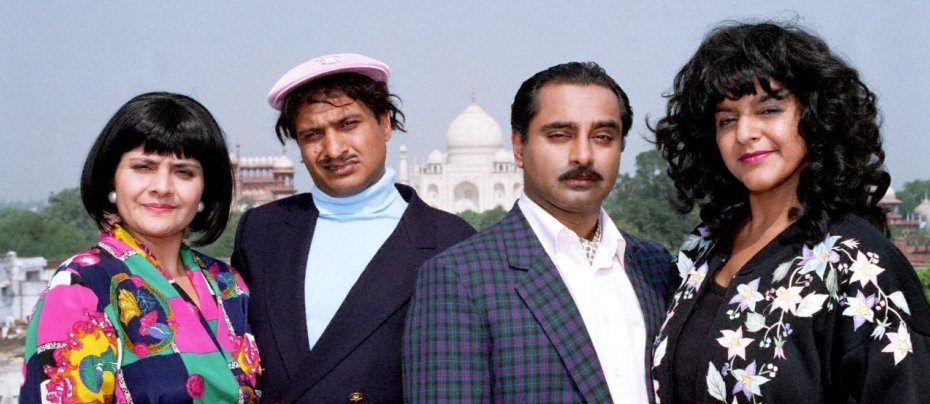

A frequently unrecognisable Martin Short comes close to stealing the whole show as Frik, helped by the gnome's multiple disguises, which involve a change not only of costume but of his whole appearance, manner, and possibly even personality. At first he seems no more than Mab's comedy relief sidekick - they make a fine double act - but his love for Morgan shows another side to him. In the end, we like him a lot.

Billie Whitelaw is perfect, as usual, as the strong minded but kind woman who actually raises Merlin. Sir John Gielgud gets very high billing for a literally "blink and you'll miss it" cameo - he did a lot of that sort of thing in his later years - as does James Earl Jones for a quick voice over. Nice work if you can get it. By contrast, producer Dyson Lovell, who trained at RADA, voices Merlin's horse, Sir Rupert, uncredited.

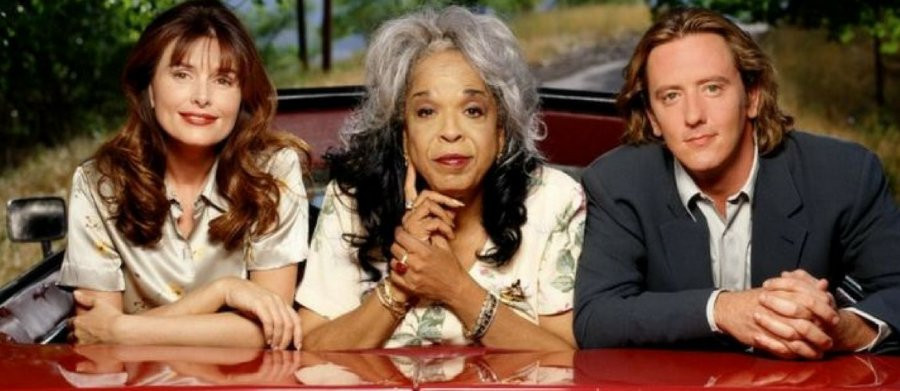

Isabella Rossellini was well cast as Nimue, one of a number of actors in the production with whom the producers had worked before on The Odyssey. Others include Roger Ashton-Griffiths, Peter Woodthorpe, Vernon Dobtcheff, and Nicholas Clay. The last is probably most famous for his role as Lancelot in Excalibur, in which Mordred was played by Robert Addie, who also appears in Merlin. Addie does not get a scene with Clay in Merlin, but he does get one with Nickolas Grace, with whom he had shared many as the principal villains, Sir Guy of Gisbourne and Sheriff Robert de Rainault, in the fondly remembered Robin of Sherwood. It is nice to think that these casting decisions were not accidental.

In what may be another genre reference, the great Rutger Hauer, the star of Khmara's Ladyhawke, provides substance as Vortigern, the biggest villain of Welsh history (he let the English in). Again, a basically unsympathetic character is given a certain internal logic and integrity - and a great deadpan shot as a castle collapses behind him.

Talking of genre connections, Guinevere is played by a very young Lena Headey: any Game of Thrones fans watching the wedding scene today will probably be screaming at the television "Don't do it, Arthur! Don't marry Cersei Lannister! It's bound to lead to trouble." It does.

The Director of Photography, Sergey Kozlov, was another veteran of The Odyssey, arguably the most important of all, because, even more than the cast, it is the look of the thing that makes Merlin so memorable. The production used, especially by the standards of the period, an extraordinary number of effects shots, far more even than the 'Odyssey.' At the time, Halmi wrote, referring to the CGI, "we could not have made this Merlin even six months ago." Ironically, it is that speed of technological advance, which continued at that pace and even accelerated, that now makes some of those effects look very dated in our Peter Jackson world.

Yet, overall, the sheer visual panache of the project endures, mainly thanks to the location work in Wales, where most - not all, but most - of the original tales of Merlin were set. Few countries in the world can boast such dramatic changes of scenery in such a relatively small space. There is a beautiful evocation of nature in many of the scenes. The costumes department also distinguished itself, even if purists might object to 2nd Century Roman 'lorica segmentata' within a few years of Medieval style tournaments. No one gets the "Dark Ages" right, but then it is not really meant to be the "Dark Ages." Arthurian Britain has always been a bright fantasy land beyond time and space, and Merlin gives a wonderful sense of that. Great use is made of colour throughout. It is as close as television can get to being cinematic.

If there is a complaint, it is that the whole thing is perhaps a bit too brisk. It would have been better to spend more time exploring this carefully constructed world and its complex characters as they deserve. Today it would be made as a full series, not a "miniseries." The BBC tried to do as much a few years later with its own Merlin, but, although some members of the cast did well, it looked like just another BBC series. It evoked none of the suspension of disbelief, a feeling one had entered a different realm, that one still gets watching the Hallmark Merlin for all its dated effects. There really is something, well, magical about it.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on January 8th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.