Private Schulz

1981 - United KingdomIt is curious that the further we get from the Second World War, the more seriously we take it. The wartime generation themselves always had a robust sense of humour about the whole thing, at least in Britain. While the image of cheery insolence may have been exaggerated for propaganda purposes, there was substance to it.

Just ask anyone who was there. Sadly, that is becoming increasingly difficult. As a result, many inaccurate impressions are creeping into the cultural image that is being presented. The psychological traits of younger generations are being projected backwards. One of these is increasing oversensitivity. We are obliged to take the War seriously for fear of causing "offence" - presumably to people who were traumatised by watching 'Schindler's List,' because people who experienced the real thing tend to go beyond such pettiness. They are offended only when truth is denied.

It is significant that a show like 'Allo, 'Allo could be written by two men who remembered the War first hand, one of whom rose to the rank of Major on active service and the other old enough to be a helpless bystander while his father went away to fight. The product of their combined trauma was a very funny satire on the pomposity of National Socialist Germany and on the absurdity of war in general - which could not be made these days.

Nor could Private Schulz, despite it being the work of one of the greatest British scriptwriters of all time. Jack Pulman had already earned the nickname of "the Adaptor-Extraordinary" for his skill in transferring classic books to the small screen. His crowning glory was his transformation of Robert Graves' supposedly unfilmable novel I, Claudius into arguably the greatest television drama ever made.

With Private Schulz, he proved that he was more than "the Adaptor-Extraordinary." Although based very loosely on a true story, Private Schulz is an original work - Pulman wrote both the script and a novel. Its success ought to have opened up an exciting new phase of his career. Unhappily, that was not to be. Soon after completing his work on the project, he died tragically young of a heart attack in his early fifties. The "miniseries" was shown only posthumously - to great acclaim.

Before moving on, two further points should be noted about Jack Pulman: he came of age during the War and he was Jewish.

Pulman understood that mockery is one of the most powerful weapons we have against totalitarianism. Totalitarians take themselves very, very seriously - a warning, perhaps, to our own times. They have no sense of humour, above all about themselves and their precious systems. Hitler himself was incensed by Charlie Chaplin's relatively mild satire in 'The Great Dictator.' The wartime generation learnt to be less afraid of him by laughing at him.

Pulman continued this tradition with a far more vicious satire on the corruption, bureaucracy, and hypocrisy of the Third Reich in Private Schulz. It differs from the comedy of 'Allo, 'Allo in that the characters are, at some level, well aware of the absurdity of some of the things they say and do, but feel that their place in the system still obliges them to say and do them - and, in as much as they can, believe them.

The story is based on Germany's historical attempt to wage economic warfare on the United Kingdom by forging currency, the innocuously named "Operation Bernhard." Most of the actual forging was done by convicted criminals housed in an isolated special block within a notorious concentration camp. This was later also the subject of a well received German film, 'The Counterfeiters,' but, predictably, with less humour.

Although it is presented with ridicule for comic effect, the theory behind "Operation Bernhard" was sound, even brilliant. The British put great effort into maintaining the international value of the pound, not least because it was needed to buy essential war supplies from abroad - propaganda about the Anglo-American relationship hides the truth that the Americans basically insisted on cash. The Germans knew from their own recent experience what inflation could do. It might indeed have knocked Britain out of the War.

Happily, while considerable effort was put into getting the paper quality and serial numbers of the banknotes absolutely right, the Germans never cracked the problem of distribution. In the end, the only real use of the forged currency was financing intelligence operations and the like, resulting in some famously disgruntled secret agents. One "victim" was Elyesa Bazna, codenamed "Cicero," the valet to the British Ambassador in Constantinople who spied on his master for the Germans, and who was played by James Mason in the feature film Five Fingers.

Even more happily, most - not all - of those involved in the project, even, astonishingly, the concentration camp inmates, survived the War. It might have spoiled the comic effect of Private Schulz if they had not.

As it is, Private Schulz is very, very funny, in spite - or perhaps because - of it being played absolutely straight by an upmarket dramatic cast.

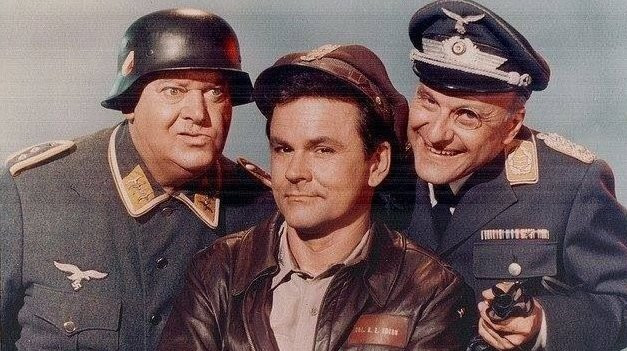

Michael Elphick is the eponymous Schulz - a name that has connotations similar to the British "Tommy Atkins" and the American "GI Joe" - a low grade criminal and reluctant conscript who finds himself at the heart of the project. Blessed with a wonderful "Everyman" quality, Elphick brings a naive charm to the role of a man out for himself but whose amiable amorality seems not so reprehensible in comparison with all that is going on around him. This was the part that proved he could be a leading man, and the talent he brings to it makes it all the more regrettable that his subsequent career was plagued, and brought to a premature end, by personal problems.

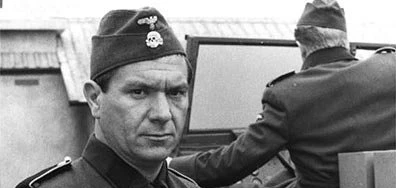

The production is, however, stolen by the vulpine Michael Elphick Ian Richardson in multiple roles, especially as the grotesque Major Neuheim. This was the show that really introduced most of the British public to Richardson, at that point a respected theatre actor, before he went on to fame as the unforgettable Francis Urquhart in House of Cards. He is the reality of the Third Reich personified - not a sadist but a self-important, self-serving middle manager of limited intellect and imagination, indifferent to everything but the system that gives him status, truly "the banality of evil." During one of his many lectures deploring Schulz's unpatriotic attitude, the camera lingers on his hand - he is wearing several expensive looking rings. It says it all.

The most surprising casting is of Billie Whitelaw as Schulz's Unattainable Object of Desire. The mega-serious friend of Samuel Beckett and doyenne of experimental drama actually seems to enjoy herself as high class courtesan Bertha. Although Whitelaw was almost fifty at the time, one understands poor Schulz's moth-like attraction to her flame. Objectively, Bertha is a ruthless, calculating, selfish, avaricious, dishonest snob - who claims she has a psychological block that means "I can't do it with anyone below the rank of Major" - but she is still the ultimate Teutonic fantasy woman.

A stupendous supporting cast includes David Billie Whitelaw Swift, Ken Campbell, Rula Lenska, Clive Merrison, Caroline Blakiston, John Savident, Roger Lloyd Pack, Vernon Dobtcheff, Michael Barrington, Geoffrey Lumsden, Pam St Clement, and Michael Denison. According to IMDb, an uncredited John Shrapnel and John Ratzenberger can be heard but not seen as newsreel commentators, and composer Carl Davis and songwriter Randy Newman are apparently bordello pianists.

Being honest, Private Schulz is not Billie Whitelaw perfect: there are inconsistencies of tone and pace that might have been ironed out had the writer been available for consultation during filming and editing - alas, he was not - and the whole thing seems to wander off towards the end.

Nevertheless, it merits rewatching, Billie Whitelaw especially in times like these, both as a savage blow against the true nature of totalitarianism, and as a fine memorial to four great talents, Elphick, Richardson, Whitelaw, and Pulman.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 18th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.