I, Claudius

1976 - United KingdomReview: JWR

Jack Pulman's adaptation of Robert Graves' I, Claudius for the BBC is a high point of modern Western culture, arguably the best historical drama in television history and possibly the best television drama of any genre.

The two novels were said to be unfilmable. Sir Aleander Korda had tried and failed - in spite of at least one great scene from Charles Laughton as Claudius. Books written in the first person are notoriously difficult to adapt, and Graves' deliberate imitation of the style of a slightly pedantic First Century Latin writer was perhaps too perfect for a mass audience.

Pulman's masterstroke was to bring the subtle humour of the subtext more into the foreground. The "Adaptor-Extraordinary" was also influenced in his characterisation by the recent 'Godfather' films. According to Brian Blessed, when the actors were having problems with their parts, Pulman told them to imagine they were in the Mafia. The parallel was immediately obvious.

Once this simple concept was understood, everything fell into place, because I, Claudius is first and foremost an actor's piece: the most important artistic choices were the casting decisions, and these had already resulted in the assembly of one of the greatest television casts of all time. It is the product of a unique moment in British cultural history, a combination of rising stars and veterans of a particularly glorious period for the London stage. It difficult to imagine it ever being replicated. Once it was in place, and the concept understood, the actors were intelligent enough to be allowed to get on with it - and director Herbert Wise was intelligent enough to let them do just that.

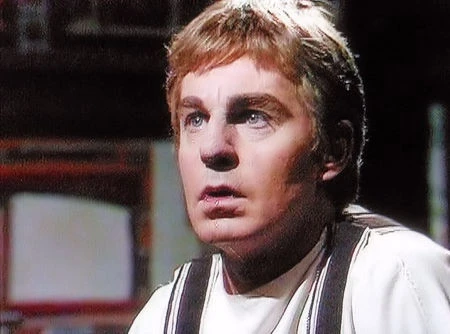

Derek Jacobi, then a highly respected stage actor barely known to wider audiences, made his career with his performance as the eponymous Claudius. He is a mostly passive observer of the turbulent reigns of three of the first four "Emperors" of Rome (actually "Principes,' meaning First Citizens, maintaining the pretence of a Republic) - before unexpectedly becoming the fourth.

The first of the Graves novels is the classic underdog becomes top dog story. A stammer and some relatively minor physical handicaps are enough to make Claudius a non-person in the militaristic Roman upper classes. Dismissed as an idiot, he is in fact intelligent enough to realise that playing the fool is his best chance of survival with all the high achievers around him wiping each other out. Bullied, he takes refuge in his books, which give him the knowledge that proves very useful when his survival strategy proves more successful than he could possibly have imagined - a hero to nerds everywhere.

However, the second novel reminds us that there are no happy endings in politics. Claudius proves a wise and effective leader, but the fact that he has known so little love in his life makes him too eager to believe it when people pretend to love him. Pulman merges both novels into one continuous narrative, so that Claudius at the height of his power is reflecting, in flashback, on his insecure earlier life from a position that is just as insecure but at a different level.

Jacobi's performance is both the spine and the soul of a complicated story. He is a sympathetic and humane representative of the viewer when he watches helplessly as those he loves are butchered, but Jacobi's masterstroke is to present a more nuanced character. We begin to see that he is not an entirely reliable narrator, that he has his weaknesses and prejudices, even if these imperfections only make us identify with him all the more. Although he is kind and decent, this Claudius is also, as he was in Graves and apparently in history, pedantic, irascible, and, yes, sometimes genuinely foolish.

The portrayals of the other three Emperors are also well grounded in what ancient sources, some more trustworthy than others, tell us about them. Although Brian Blessed is physically as unlike the historical Augustus as it is possible to imagine, he captures perfectly the essence of what the first 'Princeps' was trying to do at that point in his career. If Blessed is sometimes obviously an actor, that is the point, because so was Augustus.

After all, this was a man who twice changed his name and with it his whole persona. He had risen to power as a very young man under the name Octavian with a cold brutality that was shocking even by Roman standards. Once established as monarch in all but name, he wanted to leave all that unpleasantness behind. So Octavian became Augustus, "the venerated one," and Father of the Fatherland - an official title to which he lived up by projecting a carefully cultivated image of paternal benevolence.

So Blessed is an actor playing the role of an actor playing a role. Yet there are moments, usually only moments, when Augustus' mask of benevolence slips, and we catch a glimpse of the hard, calculating, unrelenting Octavian that still lies beneath. There is a definite chill as we are reminded that this man was, and remains, a remorseless killer.

Blessed has since acquired a reputation as "the Brian Blessed character" but anyone wanting to see what a technically skilled and sophisticated player he can be should look very closely at 'I, Claudius.' He can be just as subtle as Jacobi or any other critical favourite when the part demands.

John Hurt, by contrast, goes completely over the top as the infamous Gaius Caligula - "Little Boots" - the third 'Princeps.' He is the most entertaining of the four Emperors, but the most unsatisfying in dramatic terms. Graves had no qualms about taking the more scandalous stories from ancient sources as fact for the purposes of his novels - despite being a scholarly translator of Suetonius Tranquillus, the most gossipy of them, "the William Hickey of Imperial Rome," for Penguin Classics.

As a result, Caligula becomes something of a pantomime villain and Hurt has fun with the role. However, it is not realistic that anyone as obviously out of control as that could have survived as long he did, and modern historians are right to caution that 'Principes' traditionally viewed as "mad," including Caligula , Nero, and Commodus, were in reality far more complicated and more impressive in their public appearances.

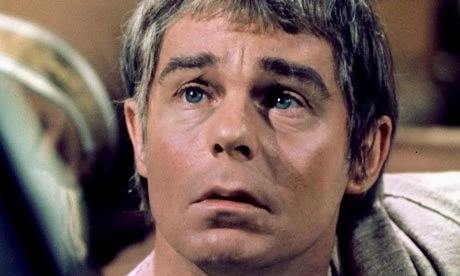

Between Augustus and Caligula came the long reign of Tiberius, played by George Baker. While Baker's performance was, like Tiberius himself, not as showy as those of the other three Emperors, it was in many ways the most interesting, again like Tiberius. The historical Tiberius was a man of enormous achievements, especially military conquests, before he became 'Princeps': truly "It would have been said that he would make a great Emperor - if only he had not been Emperor."

As he would later do as Inspector Wexford, Baker excels by simply playing it straight. His Tiberius is a dignified, reserved man struggling to control deep inner passions. He is all too aware that some of them are dark. This awareness blunts his ambition, and he can never really decide if he wants power or not, even when he has it. Baker is therefore sometimes required to play a villainous part as history demands, but he invests other scenes with a real poignancy.

Baker's performance as Tiberius is said to have influenced George R R Martin in writing the character of Stannis Baratheon in Game of Thrones.

The portraits of all four Emperors are therefore memorable in different ways - but there is a fifth evocation of power that surpasses them all. It was said that Augustus ruled Rome but Livia ruled Augustus. Wife, mother, great-grandmother, and grandmother successively to the first four 'Principes,' Livia Augusta was a towering figure in the otherwise very male-dominated political culture of ancient Rome. Sian Phillips projects Livia's authority with total credibility, and this at a time when Britain still had not had a female Prime Minister and women politicians were considered something of a novelty. It remains an astonishing performance by any standards but especially when seen in the context of the time.

Graves - probably but not certainly unfairly - has her as the biggest villain of all in the first novel, scheming, manipulating, and poisoning her way to secure the succession for her son, Tiberius, and then to try to control him. However, even Graves grants her two great redeeming features: she was genuinely patriotic and her political acumen was unsurpassed even by Augustus. She saw clearly what the Empire needed and she did it.

Phillips presents her in all her aristocratic pride - sometimes extreme natural arrogance - but this having been established, also allows her moments of vulnerability, regret, and a certain dark humour. She is basically the Wicked Queen in Disney's 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' given a three dimensional character and a legitimate point of view.

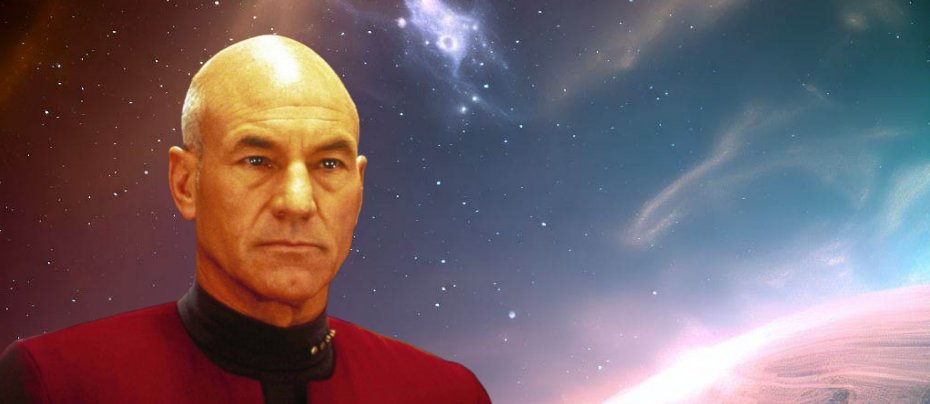

The supporting cast is simply magnificent. Patrick Stewart is a million light years from the noble Jean-Luc Picard as slimy Sejanus, the overambitious Prefect of the Praetorian Guard. John Rhys-Davies plays Sutorius Macro, Sejanus' terrifying second-in-command, as a hardened old sergeant-major - it is an incredibly precocious performance, given that it was his first major role and that he was only just over thirty. A truly great scene in which he silences all opposition to Caligula with a finely pitched combination of bluff, soldierly good humour and barely veiled threat explains a great deal about how the Roman Empire actually worked.

John Cater and the legend of Seventies television that is Bernard Hepton are great fun as a pair of bickering civil servants. Ian Ogilvy and David Robb cope well with the difficult roles of Claudius' father and brother - difficult because both died relatively young, so history presents them as rather too good to be true. James Faulkner, one of the most consistently interesting actors of the generation rising in the 1970s, makes King Herod Agrippa I the charming rogue Graves intended. If his interpretation is a little more "ethnic" than might be allowed today, it seems a historical truth that the Herodian Dynasty really did play up their Jewish credentials in order to conform with what the Julio-Claudian Dynasty wanted from client-rulers in Judaea.

Kevin Stoney looks comfortable as the astrologer Thrasyllus - hardly surprising, since he also played him a few years before in the creditable ITV dramatision of the same historical events, The Caesars. It is a good illustration of the difference between Pulman and Philip Mackie, the skilful writer of The Caesars, that Pulman makes Thrasyllus more obviously a charlatan and gives him some darkly humorous lines. He shares a literally hilarious scene with Baker's usually humourless Tiberius.

(It should perhaps be stressed that The Caesars is a great drama in its own right and would doubtless be remembered as such today had it not been overshadowed so soon after by the superior I, Claudius.)

Christopher Biggins takes the Peter Ustinov route as Nero, probably unfairly but to good comic effect. John Paul is credible as Augustus' 'consigliere,' while John Castle is nicely ambiguous as his posthumous son, actually called Postumus: we like him because he is one of Claudius' few friends but also understand why Livia and Tiberius were probably doing a public service in doing what they did to him. Kevin McNally is given little to do as Tiberius' only son but looks the part.

Stratford Johns dominates his episode as a pompous politician out of his depth in court intrigue. Bernard Hill, Norman Rossington, Simon MacCorkindale, Tony Haygarth, Charles Kay, Christopher Guard, Darien Angadi, Esmond Knight, Peter Bowles, and George Pravda each have at least one good scene in guest roles.

Those with an eye for familiar faces will also note Lockwood West, Bruce Purchase, Stuart Wilson, and George Innes, among others.

While many of the male cast were destined to go on to fame and fortune, or at least wide recognition and busy careers, the same was not generally true of the female cast, with the exceptions of Sian Phillips and Patsy Byrne, who played a poisoner as comic relief - the two share a grimly amusing scene that passes the Bechdel Test in style.

Otherwise, it is a great injustice that we saw relatively little of some of the women afterwards. We have probably heard a lot of Frances White in her voice over work but she never got the leading roles she deserved after her delightful portrayal of Augustus' tragically wayward daughter Julia as "a tart with a heart."

Nor did Shelia White, no relation, get work worthy of the potential she showed as Claudius' unfaithful but strangely naive much younger wife, Messalina. It is also surprising that Patricia Quinn, who made a good impression as a bad woman, Claudius' scheming sister, has not been offered more. Above all, why did Beth Morris, so touching as Caligula's terrified favourite sister, Drusilla, never become a household name?

Of course, Margaret Tyzack did have a distinguished career, but it was already well established by the time she played Claudius' domineering mother. Isabel Dean also deserves a respectful nod for a single, very powerful scene in which she plays a composite character who might or might not be based on a real case or cases - historians differ on this aspect of Tiberius.

Although none of the principals were particularly expensive names at the time, the number of featured players must have knocked a big hole in the budget. Nevertheless, good production values are evident in other departments too.

The much-imitated title sequence stands the test of time very well. However, the make up and prosthetics that enabled the same actor to play Claudius over five decades of his life, cutting edge in their day, have not, er, aged that well. They no longer look as convincing at they did in the 1970s. At least we have become used to better.

Great effort was put into researching the costumes, props, and sets, and it shows. Not only were they historically accurate, more important they looked accurate - which is not always the same thing.

The only drawback with the production is that in the 1970s, the BBC had neither the money nor the technology to include big set pieces. We see the Senate House and a corner of the Forum, and most of the rest is just a sequence of rooms - some sumptuous, but still basically stagey. No matter, most of the time the action is enough to hold out attention, and in some ways emphasising the claustrophobia of the Imperial Palace actually heightens the dramatic effect.

Yet anything to do with ancient Rome conjures in the public mind an expectation of Epic with a capital E. Some recent historical drama productions have demonstrated how modern CGI combined with location work might achieve that even on a television budget. That is why there is regular talk of a remake. It has usually met a negative reception because it is very difficult to see how it might improve on perfection. Even if the producers could afford their dream cast - and it might be interesting to see, say, Gary Oldman as Augustus or Tom Hardy as Tiberius - there would almost certainly be unfavourable comparisons with the original.

It has itself become part of our cultural history. When shown in America, on PBS like many BBC programmes, it redefined the boundaries of acceptability on network television. In spite of the orgies, nymphomania, adultery, and incest, it was shown on all the PBS stations as part of Masterpiece Theatre.

While this opened the doors for a lot of more prurient programming, few could argue I, Claudius was prurient. The sex and violence was dramatically necessary to tell a worthwhile story based on historical fact - or at least historical rumour.

More to the point, I, Claudius was an undisputed masterpiece, and remains to this day a shining example of how ambitious, intelligent, and exciting great television can aspire to be.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on March 14th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.