Disraeli

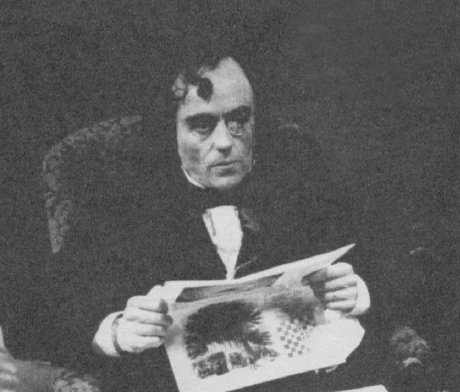

1978 - United KingdomMcShane's performance is so commanding that one soon forgets how little he looks like the original

Disraeli – 1978 4-part series reviewed by John Winterson Richards

Sometimes given the subtitle 'Portrait of a Romantic,' of which one suspects Disraeli would have approved, ITV''s brisk four-part historical drama Disraeli can only scratch the surface of the complicated, enigmatic social adventurer who had a huge influence on British politics in the mid to late 19th Century and whose political legacy endures to this day. The founder of the modern Conservative Party and the inventor of "One Nation Toryism," he is still cited by many 21st Century Conservatives, including David Cameron and Boris Johnson, as a role model.

The major problem with dramatising his life is that it all seems so unlikely. If it had been the plot of one of his own novels, it would have been rejected as too far-fetched. He was one of the biggest outsiders in the history of British politics, but he rose to power as the leader of the most reactionary faction of the most traditionalist party.

He was the son of a Jew who had converted to Anglicanism. The Jews had been a prominent part of British life since Oliver Cromwell had granted them refuge and were generally well integrated by Disraeli's time: even the Radical Irish MP Daniel O'Connell felt obliged to insert the usual perfunctory "there are many most respectable Jews" into a notorious speech mentioned in Disraeli. However, although Antisemitism was not as virulent in the United Kingdom at that point as it was in much of Europe, it was still a powerful force with which Disraeli had to contend throughout his career, and, as a telling scene in Disraeli makes clear, it was in effect impossible for a practising member of the Jewish faith to hold office until 1858. In spite of this, Disraeli did not try to hide or downplay his Jewish origins.

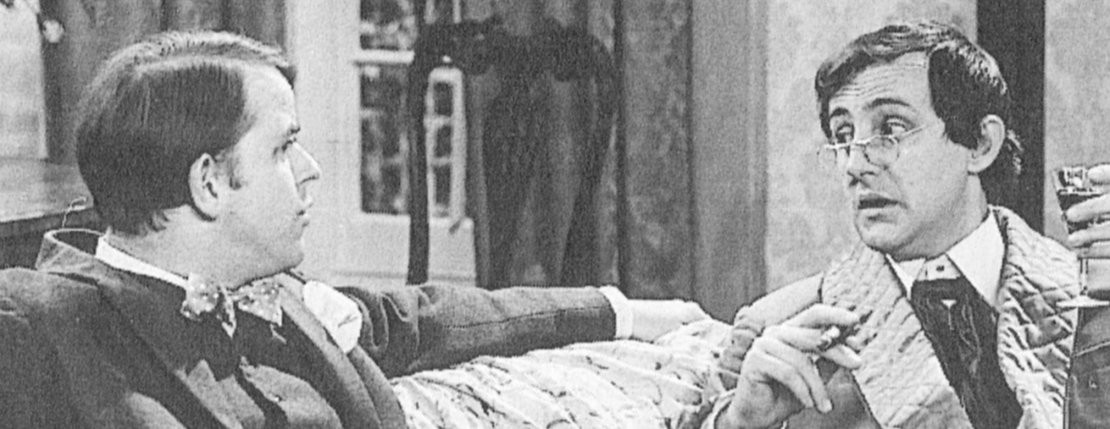

Indeed, in this and other respects, Disraeli seemed to enjoy being different, or at least determined to make a virtue of it. As a young man, he dressed flamboyantly, in the fashion of a "dandy" when it was beginning to go out of fashion, and seemed to be modelling his lifestyle on that of Lord Byron. Like a number of other conservative Chancellors of the Exchequer and First Lords of the Treasury, including Pitt the Younger and Churchill, he was haunted throughout his career by debt, in his case the result of a precocious but ill-advised attempt to establish his financial independence at a young age combined with his lavish spending habits. He was forced to earn his living, even as senior statesman, by writing novels at a time when novels were still considered not entirely respectable. Despite this, the House of Commons was far more literary in Victorian times than it is today: Disraeli shows his friendship with Edward Bulwer-Lytton, another bestselling novelist and politician who rose to Cabinet rank and a Peerage. (Contrary to the suggestion of some ignorant modern criticism, based on a single opening sentence of one of his works, Lord Lytton was a very sophisticated writer, much better than Disraeli it must be said: his 'Last Days of Pompeii' has been adapted for film and television several times, including a creditable "miniseries," but Disraeli's novels have not aged as well and have not been adapted for either screen apart from a 1921 silent film).

As might be expected of such a deliberately Byronesque figure, the young Disraeli's politics were at first Radical, but, like many such personalities, he migrated from one extreme of the political spectrum to the other. His friend Bulwer-Lytton made the same journey, and Disraeli's fellow rising star in the Tory Party at that time, William Ewart Gladstone, made it in the opposite, less frequent direction from reactionary to Radical.

Yet Disraeli never quite lost his Radical streak, and there up is a definite, consistent theme throughout his political career and writing. He had a romantic view of the history of England as a single community in which all classes were bound together by blood, history, tradition, and religion. It was certainly an idealised view, and perhaps one that could only be held by a man who always remained something of an outsider, but it enabled Disraeli to present an alternative to the alienation of industrialisation. It might surprise modern readers of his novels to find how anti-Capitalist the great Tory Prime Minister was at heart.

It might surprise them even more that he was far from alone in that. He was tapping into a tradition shared by more respectable literary Tories such as William Wordsworth, Sir Walter Scott, Jane Austen, and the Brontes. There was a paternalistic presumption that the nobility and gentry should use their privileged positions for the benefit of their tenants and the local communities of which they were the natural leaders. Again, it should be stressed that this was the ideal, and it is at least questionable if most lived up to it, but most believed in it and it was an ideal Disraeli felt should be encouraged. It was therefore natural that he should end up with the Tories, the Party of the landed interest.

For many years it seemed he and his Party were on the wrong side of history. The expansion of the franchise, urbanisation, and industrialisation meant the once all-powerful landed interest was in decline, and with it its political arm, the Tories. The future belonged to the Radicals, most of whom began calling themselves Liberals, with their belief in free markets and efficiency. Disraeli was in fact in a minority within the minority, leading a somewhat eccentric group of aristocratic young Tories, calling themselves "Young England," who shared his romantic notions and who often voted for Radical policies for traditionalist reasons. They were scorned but their Party's leadership but when the Party split over food prices, and looked set for permanent irrelevance, Disraeli was there with an ideology to counter the Liberals. His rediscovery, modernisation, and rebranding of the traditional Tory paternalism, patriotism, and populism reached beyond the declining landed interest to the urban middle and working classes. The Tories, now calling themselves Conservatives, replaced the Liberals as the natural party of Government in the last third of the Century. In power, Disraeli extended the franchise, built housing for the poor, expanded education, improved public health, and gave new rights to workers.

It is, of course, very difficult to dramatise half a Century of social, political, economic, cultural, and intellectual development, and Disraeli does not attempt to do so. Its focus is, understandably, on personalities and social drama. Yet it is at its best as political drama.

It gets off to an unpromising start, with all the worst cliches of costume drama of the time - creditors at the door, drawing room gossip, love affairs, cheap sets, too much exposition in the dialogue, men being pompous and women being flighty, etc. However, it improves a lot once Disraeli - eventually - gets into Parliament. The set pieces are well handled, especially the Parliamentary debates. The famous failure of his Maiden Speech in the Commons is given a credible spin. Even better is the scene afterwards in which a veteran MP from the other side gives some very shrewd advice, which Disraeli is wise enough to follow.

After that, we see Disraeli begin to grow as a politician. While retaining his trademark wit - the script cannot resist including most of his once celebrated "one liners," even if some seem slightly out of place - he becomes more serious. Also on advice, he abandons his flashy clothes. We see a far less frivolous Disraeli by the time he defends, on Christian grounds, the right of Baron Lionel de Rothschild, a practising Jew, to take his seat in the Commons.

A subtly dramatic scene between Disraeli and Bismarck in the final episode, apparently two old men talking politely but both knowing that peace and war are on the table, is particularly good.

Much of the credit belongs to Ian McShane in the title role. Although he is always a compelling presence, he was far from obvious casting. Frankly he was too good looking for the role. His Disraeli is perhaps the Disraeli the real Disraeli would loved to have been, the handsome, fearless hero of one of his own novels. However, McShane's performance is so commanding that one soon forgets how little he looks like the original. He projects an intensity and depth which increases as the character gets older, and which helps to explain why so many distinguished people found this initially ridiculous popinjay literally fascinating.

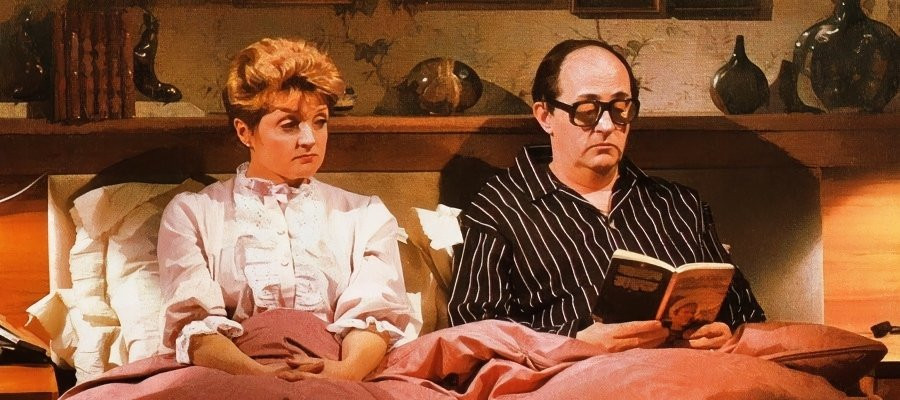

The supporting cast is not especially distinguished, but several performances stand out. Mary Peach is delightful as the not overly bright older woman whom Disraeli loved sincerely because she gave him the unqualified support he felt he could never find anywhere else. Their discussion of Milton is hilarious. Rosemary Leach does an excellent job conveying the change in Queen Victoria's attitude to Disraeli - largely in response to his shameless flattery - and transforms an outwardly cold, disagreeable character into one for whom both Disraeli and the viewer develop genuine sympathy, even liking. Brewster Mason feels authentic as Bismarck - possibly because he had already played the part in Edward the Seventh. Veteran Aubrey Maurice is suitably paternal as Disraeli's father. David de Keyser brings quiet power to his scenes as de Rothschild. Anton Rodgers enjoys himself as Lord George Bentinck, the epitome of a Tory's Tory who would rather be spending time with his horses than making speeches in the House. Patricia Hodge plays Bulwer-Lytton's beautiful wife as a neurotic, which may or may not be unfair.

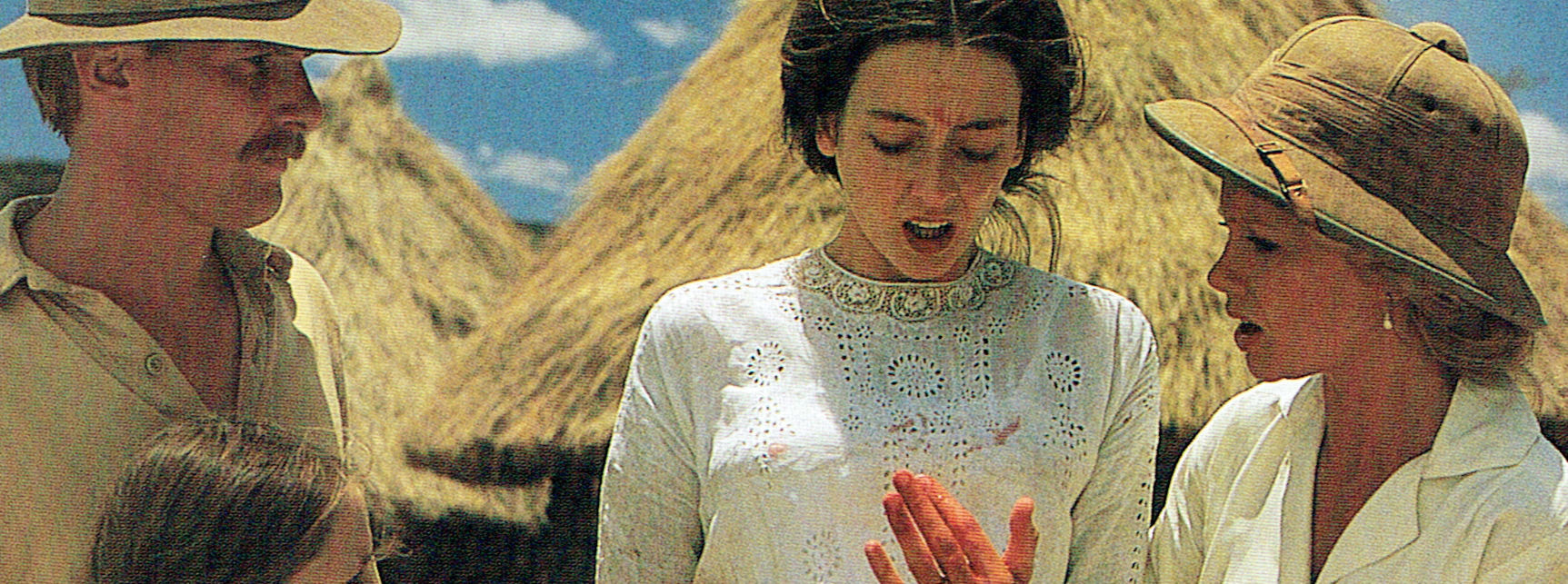

The production opens up a bit as it goes on and we get a little location work that adds a lot. It is a nice in-joke if, as it appears, that is Knebworth House doubling as Berlin - Knebworth being Bulwer-Lytton's family home. There is a lot of good attention to detail, like the Mace being placed under the Clerk's table when the House of Commons goes into Committee. It was especially interesting to see the old ceremony of Ministers receiving their Seals of Office from the Queen with a literal Kissing Hands, the Privy Counsellors in uniform, except for the Chancellor of the Exchequer in his official robes (for which Churchill later found an alternative use when he became Chancellor of the University of Bristol). The costumes, which play a particularly important role, look magnificent, especially Disraeli's colourful clothes in his early days, even if one can see why he was considered vulgar - he certainly overdid the watch chains! The hair styling and make up are also outstanding, not least in showing how the physical changes in Disraeli as he aged prompted him to change his image. Overall, Disraeli is worthy of its place in the long list of great Britain historical dramas of the 60s and 70s, and if it does not give us much of a sense of the inner Disraeli, perhaps Disraeli himself would prefer it that way.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on October 26th, 2022. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.