Wolf Hall

2015 - United KingdomHenry VIII is probably the most recognisable King in British history. It is a fact that would not displease him. He put a lot of effort into his public image, with a little help from Hans Holbein. Yet Henry is most famous for having six wives, called Catherine as often as not. He also had a number of Ministers called Thomas - including Wolsey, More, Cromwell, Howard, and Cranmer - whose careers ended as unhappily as most of Henry's marriages ...thanks mainly to Henry.

Thomas Cromwell is not to be confused with the more famous Oliver, who was the descendant of a socially ambitious Welshman who married Thomas' sister and whose son adopted the Cromwell name at a time when his uncle was the second most powerful man in England. An administrator of extraordinary ability, Thomas was the principal architect of the modern centralised State that developed under the Tudors and established what became the Church of England. However, if people today remember him at all, it is as the unscrupulous Royal fixer who bullies Sir Thomas More in Robert Bolt's great play A Man for All Seasons and its film versions.

Feeling, not without some justification, that Cromwell had been treated unfairly by history, Hilary Mantel set out to rehabilitate him in her novel Wolf Hall. It won the Booker Prize, as did its sequel Bring Up the Bodies. To be honest, the critical adulation poured on the books is a proof of the poor state of "serious" literature at the moment. This is not to say that they are bad. They are often very good. They are simply not in the same league as some of the great historical novels of previous generations. One wonders if all the modern critics and prize givers can have read that much of the genre if they think Wolf Hall is an outstanding example.

Mantel has obviously done her research and some passages are very well written - which may be the problem: one never forgets for a second that one is reading a 21st Century writer when one wants to immerse oneself in the 16th Century characters.

So Peter Kosminsky's BBC "miniseries" based on the two novels is a specimen of an unusual, if not exactly rare, animal, an adaptation that is much better than its source material.

Its superiority can be ascribed to a single factor: the cast. If present day Britain is not exactly distinguished for its literature, the British acting profession is currently on top of the world and Wolf Hall shows us why. Mantel's cold and rather distant characters are brought powerfully to life. Warm blood flows in their veins.

The masterstroke was to cast Mark Rylance as Thomas Cromwell. Sir Mark, as he has since become, has long been acknowledged as one of the great stage actors of his generation, the first Artistic Director of Shakespeare's Globe, but his screen choices before Wolf Hall were not always well advised. He was far from an obvious choice as Cromwell, but coming to the role in the full strength of his maturity, he gives a beautifully judged performance, alternating between ostentatious intelligence, deference, impudence, flirtation, and what seems like genuine humanity so that, like the characters with whom he is dealing, we are never entirely certain about him. This is the essence of the courtier. We see why Henry came to rely on him and at the same time why he was not a man to be trusted. His gentle manner and his strictly personal integrity put us off guard so that it comes as a shock when we realise that what he actually does is often very nasty.

Charles Laughton's bulk casts a long shadow as Henry. His portrayal of the King as the roaring glutton of his later years obscures the fact that as a younger man Henry was the epitome of the handsome Renaissance Prince. Damian Lewis gives us a Henry in his prime, virile, energetic, masterful, and intelligent. Having previously enjoyed great success in American shows (Band of Brothers and Homeland), in Wolf Hall Lewis made the most of the opportunity to remind British viewers that he is also one of the most substantial actors working on this side of the Pond. Despite looking nothing like Henry, apart both from being Gingers (is one still allowed to say that?), he evokes a fine sense of how unpredictable and dangerous the man was, and why Sir Thomas More compared his favour to being friends with a lion.

More himself is played by the always intriguing Anton Lesser. If the characterisation falls short, this is due to his role in Mantel's scheme of things, not to any deficiency in the performance. Wolf Hall is Cromwell's point of view, so More is the antagonist here. We are therefore given little of the great intellect that fascinated and charmed the best minds among his contemporaries. It is fair to point out that More's image as a martyr for freedom of conscience in A Man for All Seasons deserves the aggressive challenge it gets in Wolf Hall: at a time when all sides suppressed heretical thought, for political reasons more than religious, More had been a particularly zealous persecutor in his days in power. Yet that does nothing to detract from his bravery when it was his turn to be persecuted or from Cromwell's vindictiveness in pursuing him. Protecting their protagonist, Mantel and the script sugar coat this, pretending that Cromwell was more reluctant than he was.

They also gloss over Cromwell's treatment of his former ally, Anne Boleyn. Again, we see everything from Cromwell's perspective, and it has to be said that the tide of historiography is now running increasingly in Anne's favour. There seems little doubt that she was innocent of the crimes for which he had her condemned to death. It is also to her credit that the decisive moment in her falling out with Cromwell was when she complained publicly that too much of the huge income from the Dissolution of the Monasteries was going to his political associates rather than to charity and education as intended. Within weeks of that complaint her decapitated corpse was being buried in a chest that had been used for storing arrows.

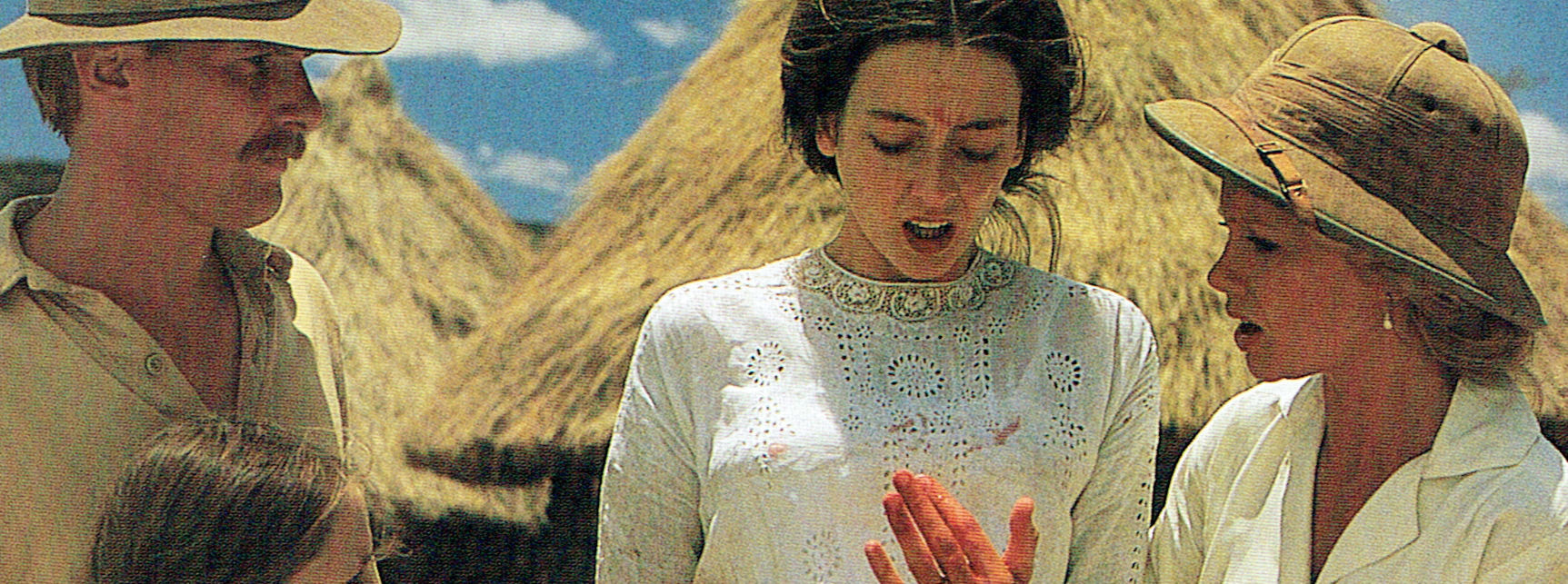

The speed and total ruthlessness with which Cromwell moved against her was astonishing. We get little sense of it in Wolf Hall. Cromwell is shown as acting in self defence, which indeed he was, but to make his position look better than it was both the novel and the script feel obliged to make Anne look worse than the current trend of history suggests. Claire Foy, who had already demonstrated a precocious talent in Kosminsky's The Promise, plays Anne as a pushy, brittle schemer, a high stakes gambler who knows she is riding her luck and whose arrogance prompts her to take on a player well out of her league. It is a credible performance in its own right but there was a lot more to the historical Anne than that.

In particular, Wolf Hall does not really engage with the fact that the basis of the initial alliance between Anne and Cromwell was their sincere Protestantism. That two such political creatures espoused it at a time when it was politically disadvantageous, even dangerous to do so demonstrates how central their faith was to them. Mantel, like much of the present cultural Establishment in Britain today, is uncomfortable with religion and unwilling to go into the Spiritual lives of her characters in any depth, and this is a major weakness in their portrayal. One cannot hope to present an accurate portrait of most of the historical figures featured in Wolf Hall without understanding how their religious convictions impacted on every aspect of their lives.

The adaptation shares this lack of understanding of religion. Thus the pragmatic Catholic Stephen Gardiner is played by Mark Gatiss as a cynic, which he most certainly was not. Similarly, there is no attempt to explore the internal struggles of Thomas Wolsey, a self-indulgent lover of worldly pomp who at the same time took his position as Cardinal Archbishop of York very seriously. Wolsey, like Cromwell, deserves at least a partial rehabilitation and Wolf Hall is a step in the right direction. A visionary statesman as well as Cromwell's mentor as an administrator, he was, again like Cromwell, a self-made man of humble origins, and his interest in justice and the welfare of the poor suggests that he never forgot it. That Wolsey retained the loyalty of a hardened operator like Cromwell, among others, even after falling from power says something of the strength of his personality. Jonathan Pryce gives us an amiable Wolsey in decline but no hint of the formidable politician who basically ran England and made him a first rank player in Continental diplomacy for almost two decades.

The cast has great strength in depth. Bernard Hill, who seems to have cornered the market in arrogant authority figures, is Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk. Joanne Whalley is a beautiful Catherine of Aragon - surely Henry could never have left her. Saskia Reeves is the sister-in-law with whom Cromwell has an unlikely affair. Charity Wakefield plays Anne's slightly dimmer sister, and Henry's past mistress, Mary - before going on to play a much brighter mistress in The Great. Harry Lloyd is Lord Percy, who seems to have been almost as gormless as his Blackadder namesake. Bond villain Mathieu Amalric is the shrewd and experienced Imperial Ambassador Chapuys. Thomas Brodie-Sangster is Cromwell's apprentice, and later his successor as Secretary of State, Ralph Sadler.

The production values throughout are excellent. Considerable effort seems to have gone for into getting the details right. The location work is aesthetically pleasing, even if there is no great sense of epic. The costumes and props are perfect. If anything, the production is too accurate - a valiant attempt to convey the reality of living by candlelight attracted complaints about scenes being too dark to follow.

Overall, Wolf Hall marks a return to form by the BBC in historical drama, a genre in which it once led the world. Comparing it with The Six Wives of Henry VIII, the series that could be said to have established that primacy, we see that they have much in common: scripts that generally try to stay close to historical sources, first class actors, and investment in production. If the 1970 production is still probably the more realistic evocation of the Tudor Court, Wolf Hall is the more entertaining, thanks mainly to the sophistication of its characters. Mantel has since published the third volume of her Thomas Cromwell trilogy, The Mirror and the Light, and the BBC has announced that work has begun on a television adaptation. That is welcome news.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 15th, 2021. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.