Rome

2005 - Uk UsaReview: John Winterson Richards

Adapting the true story of the Fall of the Republic in Ancient Rome would raise only one difficulty - what to leave out? History provides everything on a plate: huge characters, dramatic reversals, epic settings, memorable lines, sex and violence, colour and spectacle, exotic locations, battles and sieges, and political lessons that are still frighteningly relevant today.

It is simply too much, so individual plays and films tend to focus on a single episode, like the Spartacus Rebellion, the Assassination of Julius Caesar, or the doomed romance of Antony and Cleopatra, and even these tend to run long. Perhaps an extended television series is the only way to do justice to the whole thing.

Even HBO's Rome, the best attempt to date, cops out a bit by coming in late. We join Julius Caesar as a successful Proconsul in the final phase of his Gallic War. We therefore miss much of the political context. It is a pity that the producers did not secure the rights to Colleen McCullough's well researched 'Masters of Rome' cycle of novels. Then we could have had the rise of the demagogues, the terrifying Marius and the even more terrifying Sulla, the depressing truth about Spartacus, the genuinely more likeable Robin Hood figure of Sertorius, the rivalry of Pompey and Crassus, and the adventurous early life of Caesar himself. It would be great if someone could produce that someday.

In the meantime, Rome is an acceptable substitute. Its masterstroke is to view the great sweep of historical events from multiple viewpoints, especially from those nearer the bottom of the political order. In particular, two Centurions in Caesar's army provide the spine of the story, performing a function similar to that of the two robots in the original 'Star Wars'trilogy.

Lucius Vorenus (Kevin McKidd) is an honourable Rome traditionalist with aspirations for his family. Titus Pullo (Ray Stevenson) is an easy-going thug who takes a matter of fact attitude to the casual brutality expected of him. Both are credible examples of types one could find frequently in the Legions, and are based, very loosely, on real Centurions of the same names mentioned in Caesar's 'Commentaries' as being competitive in performing deeds of insane bravery.

At the other end of the social spectrum, Caesar, Mark Antony, Rome and Pompey are played by three superb actors who deserve greater stardom - Ciaran Hinds, James Purefoy, and Kenneth Cranham respectively. All give fine performances as one would expect of them, but the scripts emphasise certain aspects of the historical characters while ignoring others. So while Caesar was indeed an arrogant aristocrat, Antony a hyper-masculine chancer, and Pompey, by this stage, a burned out volcano, as they are portrayed by Hinds, Purefoy, and Cranham, there was more to them than that. What was it about these three men that compelled other men to follow them? We never really find out from Rome.

All three are presented as clever schemers, which they undoubtedly were, but it is too easy to sink into cynicism and cheap Machiavellianism. These were also men who believed in what they were doing. This is even more true of Marcus Tullius Cicero. While David Bamber's portrayal of the timid intellectual may have been fair in some respects, it is wrong to imply that Cicero was motivated by anything other than a sincere love of the Republic. In the end, he may have been the only one who was, and the tragedy of Cicero is in a way symbolic of the tragedy of the Republic - and vice versa.

Polly Walker is enormous fun as Caesar's niece, Atia, who is presented as the biggest schemer of them all. This is totally anti-historical. The real Atia gave her son, Octavius, later Caesar Octavian, later Caesar Augustus, the first Princeps, and the big winner of the whole game, the really bad advice to stay out of politics. If he had, he would have been quickly killed anyway.

The reliable Lindsay Duncan is Walker's worthy opponent. She plays Servilia, Caesar's sometime mistress, who is, again contrary to history, set up here as a serious political player and Atia's rival in intrigue. Tobias Menzies is nicely conflicted as her son, and possibly Caesar's, Brutus. Haydn Gwynne is Calpurnia, Caesar's long-suffering wife.

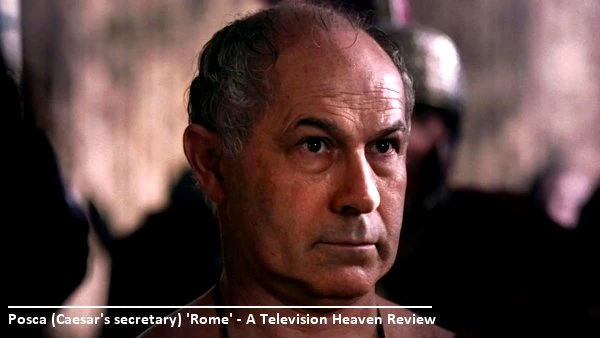

Nicholas Woodeson excels as Caesar's secretary, at first a slave but ultimately an influential player in his own right behind the scenes - and a reminder that the strict Roman class system really did offer great opportunities to the slaves of powerful people, so long as they never forgot their place. Lorcan Cranitch is effective, as he always is, as a Roman crimelord. Lee Boardman is sympathetic as a Jewish horse trader who ends up doing various odd jobs for Atia.

The most memorable character is probably the town crier or herald played by Ian McNeice. Accompanied by stylised hand gestures that seem to be a form of sign language, his announcements mix official proclamations, advertisements, and propaganda for whoever happens to be in charge at that point. He does not care - so long as he keeps his job, which he does through all the many changes of administration.

Although he is not based on a named functionary, he certainly had his historical equivalents.

In general, however, the most frustrating thing about Rome is its erratic attitude to historical accuracy. It has obviously gone to a lot of trouble to get details absolutely right, which makes it all the more confusing when it gets important points completely wrong. Just when the viewer has the right to assume that what he sees is true, he is shown what is false.

For example, in a plot point like something out of Carry on Cleo, Vorenus is made a Senator after saving Pullo's life in the gladiatorial arena when Pullo is sentenced to death there.

Now it is a surprising historical fact that Caesar did indeed promote some of his loyal Centurions to the Senate, much to the scandal of the old aristocracy. What may be more surprising is that it was actually very difficult for regular magistrates in Rome itself to sentence full citizens to death, or to fight as a gladiator, without an appeal process that would at worst reduce the punishment to exile. So, astonishing as it may seem, Rome had in effect no regular capital punishment for full citizens. Yes, you read that correctly. Check out the last chapters of the Book of Acts for an example if you do not believe it. The Romans were very legalistic.

This matters because it helps to explain why the late Republic was such a disorderly place. It also explains why, in the absence of regular capital punishment, the Romans were always resorting to the irregular kind - because they were executing each other more than ever. In the absence of regular law and order, "special powers" ruled.

The total disorder of the last days of the Republic is actually one of the things Rome conveys very accurately. In the power vacuums that were frequent between the Dictatorships of Sulla and Caesar, the legal system was corrupt and ineffective, organised crime flourished, and the streets were very unsafe. This was one of the reasons why many Romans were not unhappy to see a strong man take over.

So Rome is a useful antidote to the false impression that the Romans were always neat and tidy, wearing togas, and building straight roads. They were a violent people and, as the Republic collapsed, much of their violence was directed at each other.

If Rome gets the violence right, it gets the sex wrong. While it is true that, as a basically rural culture, the Romans had a practical attitude to sex, they were also, again as a rural people, fairly strict when it came to "family values." A high born lady would not pleasure herself casually in front of her slaves with a horse trader from the lower classes. Almost as much time separates the late Republic from the debauchery of Messalina as separates us from the Victorians.

Yet Rome is on historically solid ground when it seeks to subvert the traditional Hollywood images of nothing but pristine marble everywhere. The art and design departments deserve particular praise for their realistic blending of grunge and splendour.

Indeed, the production values in general are practically Rome faultless. This was the first of a number of mammoth international co-productions filmed in Italy in recent years that set new standards for historical drama on television. In the case of Rome, it doubtless helped to be based at the famous Cinecitta studios, where many a Roman themed epic was made for the cinema.

The acting is also what one would expect of such a strong Rome cast, Stevenson, Purefoy, Walker, and Woodeson making particularly strong impressions. The project's weaknesses are therefore more in the plotting, which is surprising given the strength of the conceptual team, headed by the mighty John Milius of Conan the Barbarian fame.

It cannot be repeated too often that in this sort of historical epic, the safest option in purely dramatic terms is to stick as closely as possible to what history is already offering on that plate.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 13th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.