Drake's Venture

1980 - United KingdomThe conflict is brought to life by two actors with something to prove...production values are excellent...

Review by John Winterson Richards

Sir Francis Drake was arguably the first of the classic adventurer heroes of the British Empire. The 1961 television show that bears his name is a typical reflection of his popular image, and if, like that image, Sir Francis Drake is heavily fictionalised, there is still an astonishing amount of fact behind the fiction. Indeed Drake's list of genuine achievements is so literally incredible that fiction sometimes needs to tone them down a bit to make them more convincing. While it must be acknowledged that some of his business practices do not meet the ethical standards of a more censorious generation, if you found yourself in a hairy situation on a ship at sea, Drake is definitely the man you would want to see up on the quarterdeck.

The 400th Anniversary of his greatest achievement, his Circumnavigation of the Globe, was the pretext for Drake's Venture, a prestige project by Westward Television, the ITV franchise holder for the South West, which includes Drake's native Devon. The well produced television film was itself a rare venture on to the national network by a relatively small company that usually stuck to its own country, and may have been intended to boost its chances of getting their franchise renewed. Alas, by a particularly cruel irony, adding insult to injury, the only national transmission of Drake's Venture in the UK was interrupted by a news flash announcing that Westward had lost their franchise.

Now back to their film

...which is actually a superb piece of television craftsmanship, suggesting that the company deserved better. Although many Britons are ignorant of the fact that Drake's Circumnavigation took place over fifty years after the first one, by the Spanish under Magellan and Elcano (see our review of Boundless), Drake's was in many ways an even riskier proposition. Magellan's experiences in the Straits that bear his name had discouraged people from using the East-to-West route he pioneered, so the Spanish had since then taken the long way around and thus turned the Eastern Pacific into their own fiefdom. Their overconfidence offered a great opportunity for Drake to exercise his unethical business practices, but he would be on his own in hostile waters far from home if anything went wrong.

The full story of the Circumnavigation would be too much for single television film with a limited budget, so Drake's Venture made the sensible decision to concentrate on a single episode, the "Doughty Plot," with the most visually exciting - and potentially expensive - aspects of the subsequent voyage passed over with little more than a few lines of exposition. No matter; because there is sufficient drama in the Doughty Plot to carry the film.

It remains one of those odd Elizabethan mysteries that tend to endure when names like William Cecil, Francis Walsingham, and John Dee are involved, even peripherally. Whether the Doughty Plot was even a proper plot seems, well, doubtful. Archdeacon Hakluyt, Drake's Number One Fan, is notably cagey in the few pages on the topic he felt obliged to insert into his great account of the Elizabethan Voyages.

Thomas Doughty had been Drake's comrade in arms in Ireland. A well connected lawyer, he was one of Drake's partners in the "Venture," the fitting out of a small squadron of privately owned warships for purposes that were kept deliberately obscure but which was very much a commercial enterprise. Also kept deliberately obscure was the extent to which Queen Elizabeth was involved in the Venture. Most of the investors were very silent partners, but Doughty, who seems to have been a personal friend of Drake's, sailed with him in command of a contingent of soldiers. Doughty considered himself a co-commander, a common arrangement at the time, but Drake, as Captain General of the Expedition, stood firm for the principle of unity of command.

It was probably no more than a clash of personalities, even if the script emphasises the class conflict aspect fashionable in the Seventies. In the end, both the common seamen and Doughty's fellow gentlemen adventurers were united in the realisation that Drake was the man most likely to lead them home safe and rich. It was probably no coincidence that Drake, who seems to have identified strongly with Magellan, chose the very spot where Magellan decapitated a mutinous subordinate, San Julian in Patagonia, to do the same. Doughty, lawyer to the end, demanded that Drake produce the Queen's commission to prove he had the right to do so. Drake's refusal is understandable: it might have revealed the deptFh of the Queen's complicity in what was essentially piracy against Spain. Probably because he realised that the other officers understood this, Doughty accepted his fate with the Christian resignation and good humour expected of a gentleman under circumstances that arose quite frequently under the Tudors. The Queen's subsequent tacit approval of what was undoubtedly an illegal execution - doubtless due to gratitude to Drake, partly for keeping her name out of it but mainly for her immense share of the Venture's profits - is said to have established the widely accepted, if still legally dubious, notion that a Ship's Captain at sea is answerable only to God.

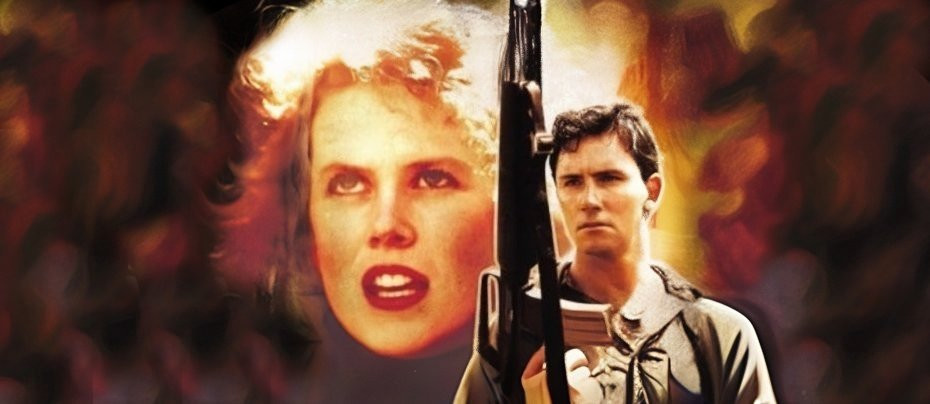

The conflict is brought to life by two actors with something to prove. Having finished The Sweeney not long before John Thaw took the role of Drake, complete with a creditable Devonian accent, to show the world that there was more to him than Jack Regan. He succeeds, even if there is still a bit of the surly Regan-esque working class hero about his Drake. He certainly projects the air of confidence and competence that made Drake a natural leader. One can understand how a discontented crew rallied to this Drake when he offered them hope and fear - hope of wealth and fear of his wrath. Thaw always did suppressed aggression well, so it is perhaps churlish to complain that he does not balance it with the affability of which Drake was also capable, at least when not losing his ferocious temper. Another minor complaint is that the script could have made the point that knowledge of Drake's previous exploits at this point must have been an important additional factor in swinging the crews behind him against Doughty.

Paul Darrow was still on Blake's 7 at the time of filming and under the same need to demonstrate he was more than a single part. It is therefore not to his advantage that for much of the time the script calls on him to play Doughty as a sort of would-be Avon, except without Avon's decisive ruthless streak. In the end it is Drake who had that quality. Doughty's final scenes, in which he attempts a brittle reconciliation with Drake, enable Darrow to stretch his acting muscles a bit more and they certainly stick in the mind. However, one cannot help thinking of another curly haired Captain with an insubordinate subordinate, and wondering that a lot of problems might have been avoided had Blake acted more like Drake.

The rest of the cast, who have little to do, include Charlotte Cornwell as Queen Elizabeth, David Ryall as Walsingham, and Esmond Knight as Dee (Knight is best remembered for playing another Welshman, Fluellen in Olivier's Henry V). The dialogue is commendably in period, with some lines quoted directly from original sources. Thaw in particular seems to enjoy the excuse for some semi-Shakespearean delivery. It is a refreshing change to hear this sort of thing after a decade or two of characters in "historical" drama usually talking, acting, and apparently thinking like obvious 21st Century types. The script is commendably literate and accurate. Where it speculates it does so within the limits of the primary sources.

Production values are excellent, at least by the standards of British television of the time - in the days before CGI. After Thaw and Darrow, the biggest star is a full size replica of the Golden Hind (London's Golden Hinde, a seaworthy reconstruction now berthed at St Mary Overie Dock, Southwark) - that full size only emphasising how small it was and how brave were the men who crossed the world in it. Rewatching Drake's Voyage for the first since that single broadcast, over forty years before, your reviewer was, once again, left wondering when and how they forgot the secrets of making proper historical drama like this.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on April 29th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.