Number 10

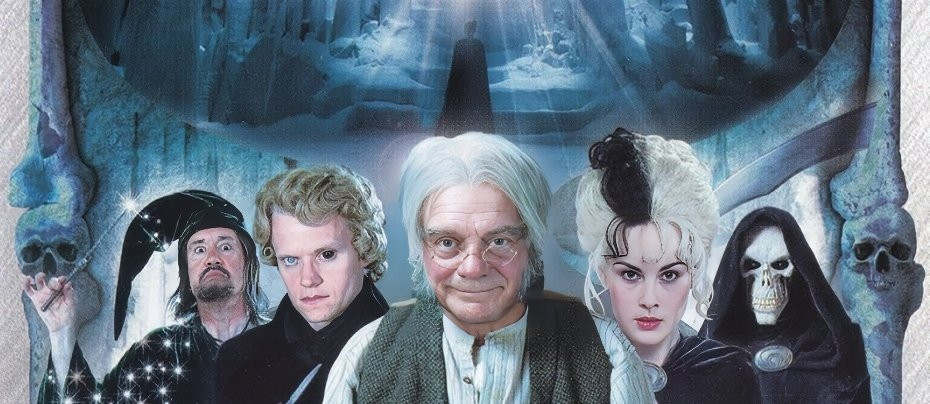

1983 - United KingdomA whole host of stars feature in this historical anthology series telling the stories of seven Prime Ministers and their time in office at London's most famous address

Number 10 is reviewed by John Winterson Richards

Terence Feely is not as well known as he deserves. He was up there with Jack Pulman, Brian Clemens, Terry Nation, Philip Mackie, James Mitchell, and the brothers Troy and Ian Kennedy Martin among the greats of the Golden Age of British television drama. An extraordinarily prolific writer, he had the knack of being in at the start of classic shows including The Avengers, The Prisoner, and Callan (he was not, however, the "creator" of the last as is sometimes stated: that was James Mitchell; the then more experienced Feely was brought in to develop Mitchell's Armchair Theatre script into a full season; he also wrote three of the best episodes). Other credits include The Saint, The Persuaders, The Protectors, The New Avengers, The Return of the Saint, UFO, Space 1999, and Arthur of the Britons. He was in effect the head writer of the last, but there was no real equivalent of the American "showrunner" Executive Producer in British television when Feely was most active, which is a pity because the role would have suited him perfectly. The closest he got was co-adapting Mistral's Daughter, a superior American "miniseries" when that format was at its zenith, and devising The Gentle Touch and its sequel C.A.T.S. Eyes.

Feely was also a production company director, a journalist, a playwright, and a novelist. In the last capacity he wrote Number 10: the Private Lives of Six Prime Ministers, more a collection of short stories based on the doings of several historical Prime Ministers in their eponymous official residence than a novel. Soon after - apparently subsequently not simultaneously - he adapted this book into an anthology series made by Yorkshire Television for ITV, throwing in an extra Prime Minister. For this ostentatiously classy project he teamed up with the respected director Herbert Wise, whose laurels were still fresh from I, Claudius.

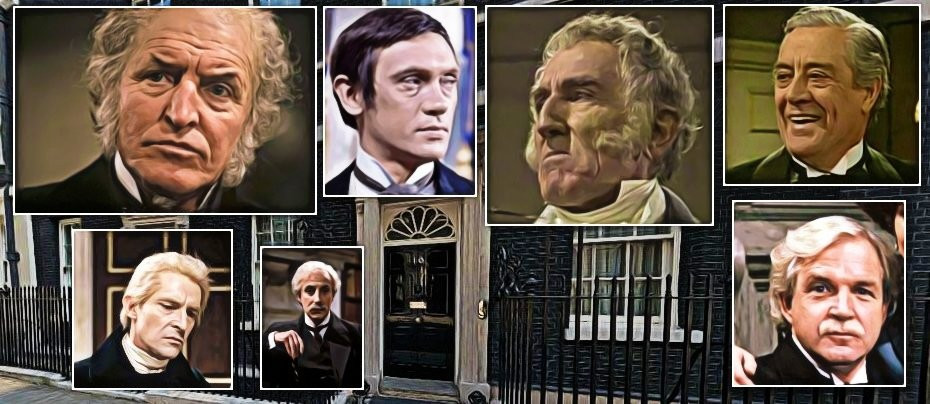

Like most such anthologies, Number 10 suffers from the lack of a unifying story arc. The house itself, 10 Downing Street, is supposed to be the thread that runs through the whole project, but we find out very little about it so that it is little more than background, which is a missed opportunity. The effect of a lack of a common story to the whole is exacerbated by the lack of characters who remain constant through different stories. This is to be expected in a drama covering a timespan of about 150 years, but even where there is an overlap, as there is between Disraeli and Gladstone, and between Asquith and Lloyd George, there is a noticeable reluctance to use the same characters. Only Neville Barber, as King George V, appears in two episodes - and, incidentally, is very good in both.

There is also the problem of setting up the separate historical and political context of each episode. The dialogue is full of exposition, much of it "on the nose." Feely is sometimes too eager to cram in facts that he discovered in his extensive research: although these are usually interesting in themselves, the way they are inserted into conversation often sounds forced, so that the series sometimes comes across as an educational "docudrama."

Overall Number 10, again like most anthologies, delivers a great variation in quality. Two episodes touch greatness, two more come close, and the other three are saved from mediocrity only by strong casting.

The first is possibly the most memorable. It gets off to a witty start as a well-dressed gentleman comes out of the fog of late 19th Century London to approach two Cockney working girls on a street corner - but if we think we know where this stereotype is leading - we are completely wrong. Denis Quilley is not obvious casting as William Ewart Gladstone, but he certainly conveys Gladstone's energy and forceful personality, and he brings credibility to the script's tactful middle position in the debate about the Prime Minister's unusual hobby (one which prompted his sons to provoke a successful libel action after his death). However, light comedy turns abruptly to tragedy and serious issues are raised. A strong supporting cast includes Celia Johnson as Mrs Gladstone, John Cater as Gladstone's clergyman son, and Frank Middlemass, James Cossins, and Jeremy Sinden as Lord Granville, Sir William Harcourt, and Lord Rosebery, members of Gladstone's Cabinet.

It is perhaps ironic that in the second episode, Ramsay MacDonald, Britain's first Labour Prime Minister is played by Ian Richardson, who was later to find fame as a fictional Conservative Prime Minister, Francis Urquhart, in House of Cards. The script presents MacDonald at first as an almost saintly man, taking an extremely sympathetic view of some decisions which are actually quite questionable to put it mildly, only to have him resolve in high Shakespearean style to be a villain in the final act. This is in accord with traditional Labour Party historiography, or perhaps demonology, but it does not bear scrutiny: MacDonald was neither as heroic nor as villainous as he is presented here - rather he seems to have been a well-meaning politician, with all that word implies, who found himself completely out of his depth in high office with no prior experience. Lesley Joseph appears briefly in a minor role.

The third episode may have been an attempt to counter the hagiography of the BBC's The Life and Times of David Lloyd George, starring Philip Madoc, a couple of years before. Here Lloyd George is played by John Stride, an English actor who enjoyed putting on a Welsh accent, as he did again to great effect in The Old Devils a few years later. The script exaggerates both Lloyd George's amorality and his dominance (it is ridiculous to suggest that a Criccieth solicitor had to explain convoys to the Royal Navy, which had been running them for centuries). Yet, just as we assume that he is once again going to be the hero of his own romance, the episode is effectively stolen by Rhoda Lewis as Margaret Lloyd George putting the old goat in his place. Garfield Morgan, of The Sweeney fame, is interesting casting as Sir William Robertson, the only British soldier ever to rise from Private to Field Marshal, but the part is not well used. Iona Banks strikes an authentic note as a formidable Welsh housekeeper.

Bernard Archard is one of those actors whose face is more familiar - mainly from supporting parts in the Sixties and Seventies - than his name. The fourth episode of Number 10 gave him a rare leading role and he certainly made the most of it: his is possibly the most authentic portrayal of the Duke of Wellington ever committed to screen. Beneath the carefully cultivated image of the stern, cold aristocratic professional soldier, Wellington really does seem to have been a sensitive soul, who preferred the company of women and children, and who felt great affection for those closest to him in a tight knit inner circle and was the object of genuine affection in return. The set piece of the episode, the only duel ever fought by a British Prime Minister in office - ironic, given Wellington's strong disapproval of the practice and suppression of it as Commander in Chief in the field - is handled with great skill, giving a good sense of the social awkwardness that must have characterised most such occasions. The supporting cast includes Gabrielle Drake, Philip Latham, Richard Kay, Michael Barrington, and Gawn Grainger on fine Flashmanic form as the Duke's scapegrace nephew.

The fifth episode is the weakest because hardly anything happens. The House of Lords is reformed but that evokes little emotion. We are instead invited to invest in the characters of the Asquiths. The problem with that is that the Asquiths always come across, as they do here, as beautiful, brilliant butterflies with no depth. David Langton is believable as H H Asquith, KC, one of the great barristers of his generation but a man who seems to have applied a lawyer's detachment to all the other aspects of his life, which does not make him a very engaging protagonist. Dorothy Tutin is more entertaining as his wife, Margot, an eccentric aristocrat, who, in a completely different way, is just as superficial. John Wentworth, Wensley Pithey, and Tony Steedman are all more sympathetic as Asquith's predecessor Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, King Edward VII, and a pragmatic rebel Lord respectively.

The episode on Disraeli, like the episode on Lloyd George, may be a response to another series that had then recently been shown. Where the 1978 Disraeli, with Ian McShane in the lead, portrayed "Dizzy" as an emotionally guarded man, as he undoubtedly was and necessarily so, the Number 10 version peaks behind the facade a bit more. Richard Pasco was a very distinguished stage actor who made few forays on to the screen but when he did they were worth watching. He gives us a more human, vulnerable, even needy Disraeli. The famous Disraeli witticisms are, of course, out on parade but there is less cynicism in their delivery, more of a weary old performer doing what is expected of him. Zena Walker plays Queen Victoria as a lot brighter than she might appear, which is probably accurate.

The series saves its best until last - a real powerhouse performance by Jeremy Brett as Pitt the Younger. At this point, he was at the peak of his powers, just before going on to do The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, where he won glory as, in the opinion of many and against very strong competition, the definitive Holmes. He holds nothing back here. What an actor! Indeed, knowing what we now know about Brett's personal troubles, we might wonder how much was acting. Either way, we see a man reaching deep inside himself, despite being terrified of what he might find there. Caroline Langrishe is delightful as the woman Pitt really does love - tragically for both of them - which makes his final decision incomprehensible, possibly literally insane. The eclectic but effective cast also includes Keith Barron as his brother, the always impressive Alfred Burke as their father, the great scene stealer David Ryall as the self-confident Radical playboy Charles James Fox, and William Simons as a slightly over familiar servant.

The production values vary like the scripts. There is some good location work, but the emphasis is still on Downing Steet. There it must be said that some of the sets are of their time. The fact that each episode demanded its own costumes left little in the budget for big crowd scenes, so the whole thing remains very intimate, which is perhaps appropriate to the original concept. Yet it is a pity we never really get a sense of the floor plan and scale of the famous house, so the linking device never really functions. The Brett episode is still worth watching on its own simply for his performance. From there the viewer might be tempted to move on to watch Pasco, Archard, and Quilley. The other three episodes are for completionists only. Overall, the project did not succeed in its ambitions, because those ambitions were too great for a limited series with a limited budget. The anthology format was always against it. There was no time to develop context and character, especially with Feely trying to cram too much fact and not enough story into each episode. This is not to denigrate Feely's skill: he obviously wrote the series as an actors' piece and as such it does not disappoint.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on November 3rd, 2022. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.