The Master of Ballantrae

1984 - United KingdomReview by John Winterson Richards

HTV (Harlech Television), who held the ITV franchise for Wales and the West Country for many years, developed a strange affinity with the stories of the great Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. Following the success of their 1979 adaptation of Stevenson's Kidnapped, starring David McCallum, they teamed up with the American company Hallmark to film another Stevenson story set primarily in Scotland, The Master of Ballantrae. HTV were later to go on to complete their Stevenson trilogy with John Silver's Return to Treasure Island - based on characters from Stevenson rather than on any of his books - which was at least set partly in the West Country.

Hallmark, noted for their sumptuous adaptations of prestigious literary properties and well-known stories, were in many ways the ideal partners for HTV, bringing to the project much higher production values than were usually accessible to British television companies at the time. As a result The Master of Ballantrae often looks quite cinematic and was shown in the United States as a rather long "television movie." In the United Kingdom, it was shown as a two-part miniseries, which is probably the best way to view it.

The novel is full of interesting ideas but never achieved the popular or critical acclaim of Stevenson's most successful works. The basic concept is a very old one, as old as Cain and Abel, the conflict between two brothers, one of whom is generally portrayed as good, the other as evil. It is usually the older brother, the legitimate heir, who is portrayed as the good one, while the younger brother, physically weaker and less masterful, who is envious and reduced to plotting to get his way. Think of Esau and Jacob, who are mentioned specially in The Master of Ballantrae, or Richard the Lionheart and John Lackland. Such wicked younger brothers often grow up to be archetypal wicked uncles.

Stevenson subverts tradition by making the younger brother good and the older brother evil. Yet he plays with the reader. The noble younger brother seems at times to be lured to the dark side while there are moments when the older hints at being not totally bad and the reader might wonder if he is entirely beyond redemption. After all, the manly anti-hero who changes his ways is one of the most attractive tropes in fiction. Stevenson himself seems to have lacked the nerve to go all the way along either the subversive or the traditional route, and the melodramatic conclusion to the novel is unsatisfying.

Its most famous adaptation, the 1953 feature film that was the last of Errol Flynn's swashbucklers for Warner Brothers, acknowledged this weakness in the book implicitly. Since Flynn was playing the title role, it was necessary to make the elder brother the definite hero and the commercial reality of cinema tacked on an artificial happy ending that rather missed the point of the novel. This unhappy compromise resulted in both one of the weakest of Flynn's star vehicles and one of the weakest of Stevenson adaptations.

The television film thirty years later learned from this mistake and wisely stuck closer to the book. There are, however, subtle differences. In particular, the suspense of the possibility that the two brothers may both switch between good and evil is maintained more effectively than it is even in the novel.

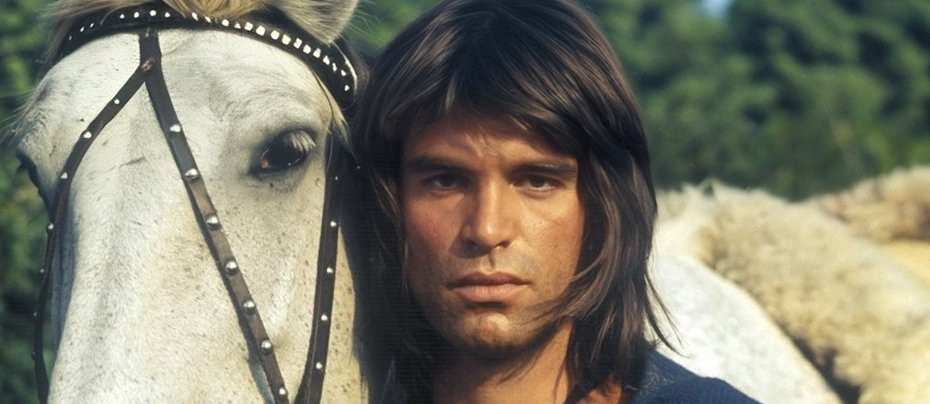

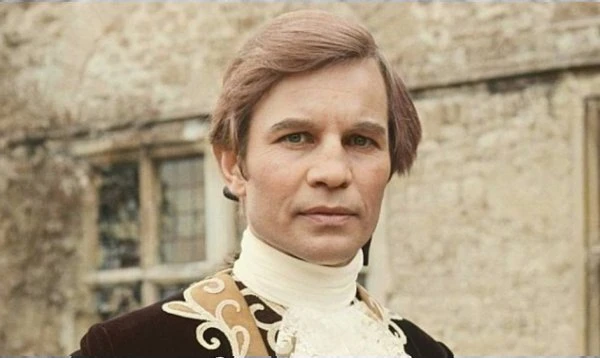

This is due in large part to the casting. Like Flynn, Michael York was an already experienced swashbuckler, best known for his excellent d'Artagnan in Richard Lester's definitive The Three Musketeers, so he was an obvious choice for the title role in a historical adventure of this type. The difference is that there was always a bit of an edge to Flynn and the characters he played, hinting at the capacity for dark deeds unless saved by the love of a good woman (probably Olivia de Havilland): this "bad boy" image was part of Flynn's appeal. York, by contrast, cannot help coming across as likeable. So even as his character does and says ever more wicked things, the viewer still expects his inner nobility to be revealed in the final act.

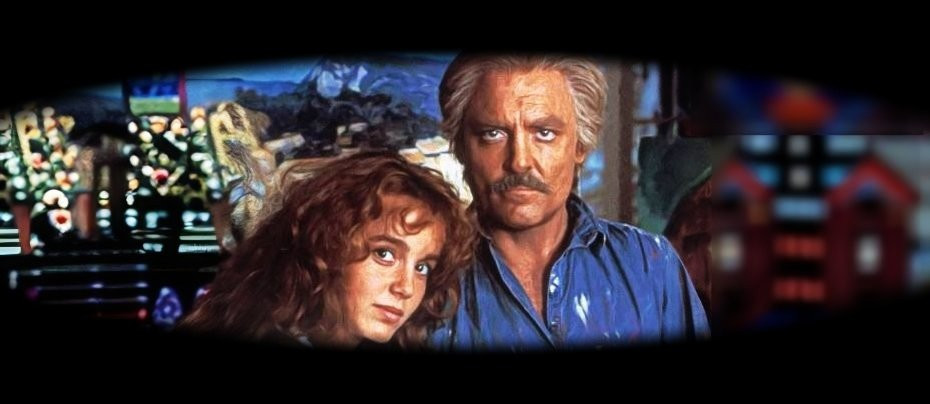

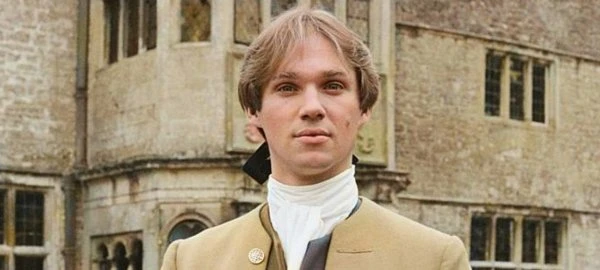

Richard Thomas is less obvious casting as the younger brother, but fits the role so well that one soon forgets he is an American actor playing a Scottish aristocrat. He is reported to have wanted to distance himself from his wholesome image as John-Boy in The Waltons, so his character's increasing instability under pressure attracted him. He succeeds in getting this across very effectively, so the possibility of a third act reversal is maintained on both sides.

The inciting incident is the 1745 Jacobite Uprising in Scotland, the crucial historical event that also precedes Kidnapped. The eponymous Master - the courtesy title traditionally held by the oldest son of a Scottish Peer - wants to fight for the Jacobites, and so does his younger brother, but their canny father explains that the best way to keep the family estate safe in a civil war is to have a son on either side. The Master "wins" the toss of a coin and goes off to fight for the Jacobites - who promptly lose. The Master therefore becomes a fugitive, a pirate, an exile, a soldier of fortune, and a colonial adventurer. Through all his tribulations he develops an irrational resentment towards the younger brother sitting comfortably at home while he suffers, ignoring the fact that this was his choice and not his brother's preference.

He retains a romantic image as a noble soul who sacrificed everything in a good cause that at first fools everyone except his brother and his brother's faithful steward, Mackellar. In the book it is eventually revealed that even this image is based on lies but the adaptation holds back from making him such a complete villain and this is actually the right decision. The book also aspired to be a globetrotting saga with events taking place on three continents, but since Stevenson was unfamiliar with India and with those parts of the Eastern United States where the final act takes place, it does not have enough local colour to develop this aspect. The same is true of the adaptation, if for a different reason: the filming took place in England, Scotland, and Wales. The locations look good and are appropriate for their scenes, but, like the book, it does not feel like the international epic it might have been.

Ian Richardson is well cast as the loyal Mackellar. Given his later fame in a single role, as the immortal Francis Urquhart in the House of Cards trilogy, it is good to be reminded that the versatile Richardson was very much in demand for at least a decade before. He was usually cast as authority figures, so it is also good to be reminded that he was just as effective on those rarer occasions when he was granted a more sympathetic role. Here he is the warm heart of the piece and, to be honest, the only character for whom we really care as the integrity of Thomas' younger brother, who is supposed to be our hero, begins to crumble under provocation.

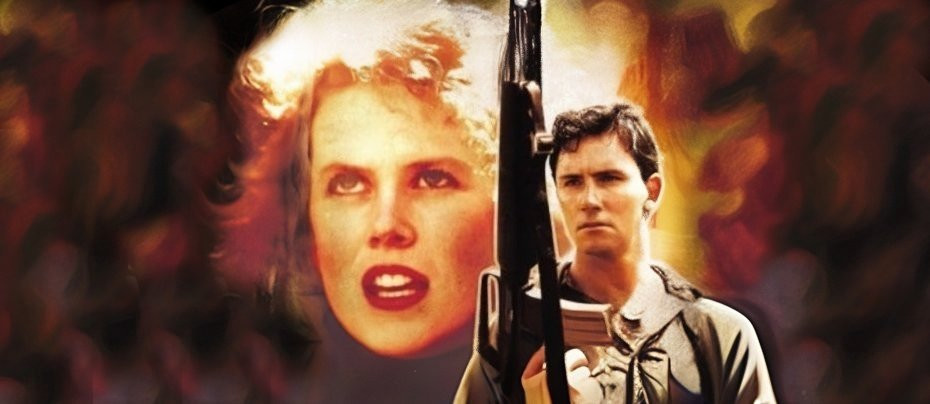

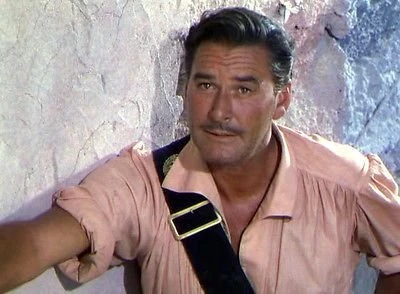

That said, we end up caring more than we ought for another character, the roguish Irish mercenary Colonel Burke, played by a perfectly cast Timothy Dalton shortly before he found the stardom he deserved as James Bond. There was always a touch of Flynn in Dalton in his prime - check out that criminally underrated feature film The Rocketeer - and one cannot help feeling this adaptation might have been closer to the book if Dalton and York had swapped roles.

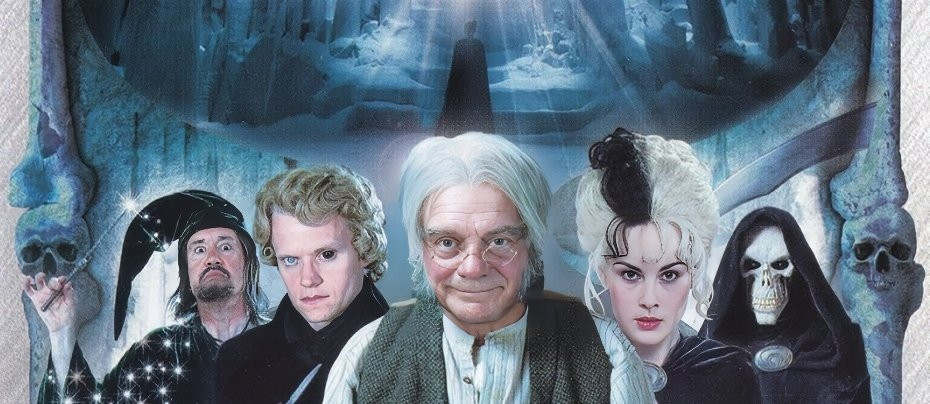

Dalton enjoys a welcome reunion with his Flash Gordon castmate Brian Blessed as the pirate Captain Teach. The novel makes it clear that this is not the famous Captain Teach, better known as Blackbeard, who had been killed over twenty years before, but a "wannabe" trading on his name. This is a pity because if ever a man was born to play Blackbeard it is Brian Blessed. As it is, he makes the most of the opportunity, and evidently enjoys himself, going full Blessed. HTV soon gave him another chance to turn pirate, as a memorable Long John Silver in Return to Treasure Island, in which he was in fact relatively restrained.

Nickolas Grace is another cast member who went on to enjoy further success in HTV historical drama soon after - as an unapologetically villainous and delightfully over the top Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin of Sherwood. Here, with appropriate - or, arguably, "inappropriate" - make up he plays a part he would not be allowed to play today, an Indian fakir. It is worth noting that his friendship with the Master seems genuine, as does Burke's in this version - in the book the Master is disloyal even to Burke, who becomes disillusioned with him.

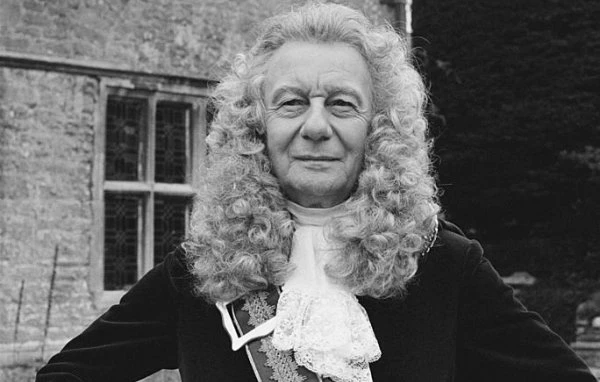

Sir John Gielgud won an Emmy Nomination as the father whose shrewdness has a definite blind spot when it comes to his unworthy son and heir. To be honest this nomination was probably a product of Gielgud's late career renaissance following his success in the feature film Arthur (1982) and subsequent Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. It was still not enough for the opening credits of the American version to spell his name correctly.

Other familiar faces from British television around this time in the cast include John Hallam (another Flash Gordon alumnus), Ed Bishop (UFO, Oppenheimer, Whoops Apocalypse), and Brian Coburn (just about everything historical in the UK back then) as American Mountain men, the latter's character actually named Mountain. Pavel Douglas (Lovejoy) appears briefly and uncredited as Bonnie Prince Charlie. The Internet Movie Database (IMDb) claims Don Henderson and James Cosmo also turned up in uncredited minor roles - if so, you have better eyes than your reviewer if you spot them.

It has to be admitted that the accents are all over the place, with Richardson, the only Scot among the principals, predictably the only one showing any consistency. No matter. This is not meant to be an authentic dramatisation of society in Mid 18th-century Scotland. It is intended only as a bit of escapist fun, and as such it succeeds admirably.

The ending is close to the book and therefore slightly disappointing, but there is one big improvement and a nice bit of ambiguity at the very end. Stevenson hints at it, but, given his time, can do no more. One suspects he might agree the changes here actually improve his story.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 1st, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.