Porterhouse Blue

1987 - United KingdomReview: JWR

Although he is probably destined to be remembered for a single role, Sir David Jason is a versatile actor who has enjoyed a wide ranging career. He is obviously at home playing it for laughs, most successfully in Only Fools and Horses, but he has also proved that he can play it straight, most movingly in the Great War drama All the King's Men. In Porterhouse Blue, he does something else again: he plays it straight in a comedic role and so gives arguably his most accomplished performance to date.

An adaptation of a Tom Sharpe novel, Porterhouse Blue is a fairly vicious satire on what is supposed to be the very pinnacle of British higher education. Until fairly recently, it was still possible for a reasonably bright young man - they were usually men - who landed a Fellowship at one of the more prestigious Oxbridge Colleges to look forward to forty years of free accommodation and fine dining in return for very little work with negligible threat of redundancy.

Things have changed a bit since then, especially since the Dearing Report drove a coach and horses through the universities sector. One cannot help wondering if Porterhouse Blue itself might have influenced Dearing's Committee, its establishment, and the implementation of its regime of allegedly more "efficient" academic management. If so, not for the first time, television destroyed what it portrayed by portraying it.

The fictional Porterhouse is an obvious reference to the famously reactionary Peterhouse of the University of Cambridge - Sharpe had gone to rival Pembroke College. The adaptation was put in the distinguished and capable hands of Malcolm Bradbury, himself an academic and satirist of universities - in his case, the more modern "plate glass" universities. Perhaps this gave him a more negative view of the medieval universities that many in the younger parts of the sector see as trading on past glories. Either way, he did not pull his punches.

The nomination of a new Master of Porterhouse falls to the Prime Minister, who uses it as a pretext to rid himself of a mediocre subordinate Minister, Sir Godber Evans. As it happens, Evans was an undergraduate at the snobbish Porterhouse, where, as a former grammar school boy, he had a thoroughly miserable time.

He therefore sets out to destroy the Porterhouse he hates through "modernisation" - Evans would surely have loved Dearing and vice versa. Yet his brusque, authoritative manner hides a man who is dimly, just dimly, aware of his inadequacy, and dominated by his wife, a product of the left wing of the aristocracy, to whose wealth and connections he owes his whole career, such as it is.

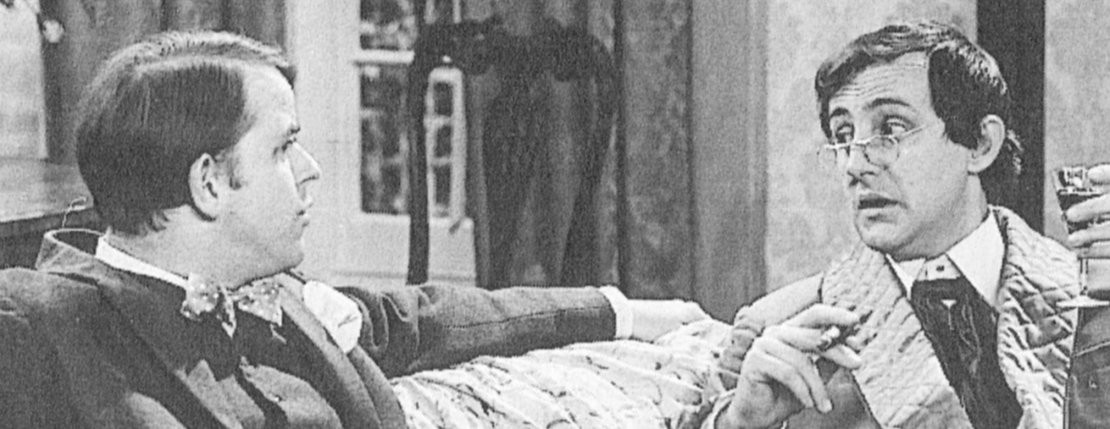

This was a part that could have been written for Ian Richardson, who, of course, plays him to perfection. At that point in his career, Richardson was already established as a man to watch, in every sense, even if true greatness, in the form of Francis Urquhart in House of Cards, still lay ahead of him. In some ways, Evans is a dress rehearsal for his Urquhart - but only in outward appearance: beneath the arrogant exterior, Evans has none of Urquhart's total self-confidence.

We see that in his interaction with his wife, Lady Mary, played by Barbara Jefford. A tireless "do gooder," her hereditary passion for social responsibility is not accompanied by much in the way of tact, sensitivity, or genuine sympathy. One cannot help thinking of the line in C S Lewis to the effect that she is the sort of woman who lives for others - and you can tell the others by their hunted expression.

She pushes her husband to ever more radical change. This increases his conflict with the Senior Fellows of his College. Played by a fine gaggle of character actors, including Paul Rogers, John Woodnutt, Lockwood West, Willoughby Goddard, and Ian Wallace, they are united in their opinion that one of them should have been Master rather than the outsider Evans - even if they cannot agree which. They are also united in their horror at the reforms proposed by Evans, especially in relation to the College's extravagant traditional dining arrangements. Evans does have an occasional ally in the Bursar (Harold Innocent) who is the only one who understands how the whole thing works and feels undervalued by the others - a common type in such organisations.

However, the most formidable opponent of change is the Head Porter, Skullion (Jason), an impressive figure who is guardian of the College's secrets. His family have served Porterhouse for generations, and, like many hereditary servants, he values his little bit of status so much that he has become more conservative than those he serves and stauncher in defence of their interests than they are themselves. His life is regulated by an absolute belief in hierarchy and in following the rules, both written and unwritten.

It is this respect for the proper order of things that makes him ruthless in preventing undergraduates sneaking into the college late at night - but also means he will not report them if they succeed, even if he knows exactly who they are and is injured in his failed attempt at interception.

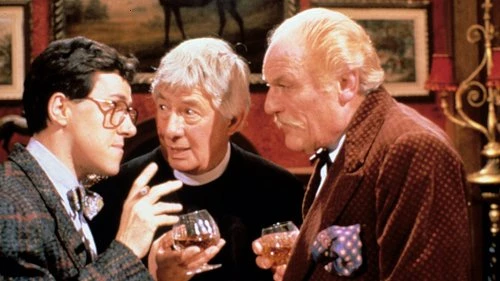

He has an inbred respect for "gentlemen" and looks down on "scholars," who are rare in Porterhouse. It is to one of these "gentlemen" that he turns for help when he begins to fear that Evans is out of control. This is Sir Cathcart D'Eath - there is nothing remotely subtle about all this - an old Porterhouse alumnus, now a louche landowner with more than a touch of Flashman about him, except that he reeks of the unquestioned entitlement of Old Money. He shares with Skullion the absolute confidence that comes with knowing his place in the order of things - in his case, at the top.

D'Eath gives the magnificent Charles Gray one of his very best roles. Actor and character exude the same natural authority. When D'Eath speaks, he takes it for granted that others will listen, even if he probably does not care that much what they do. He observes, perceptively, that men who appear clever are often stupid - and when he goes on to say that it used to be that men looked stupid but were clever, he could easily be speaking of himself.

While he is indeed far more intelligent than he looks, D'Eath is blinkered and therefore far from infallible. He makes a mistake in looking to pretentious BBC man Cornelius Carrington (Griff Rhys Jones), another Porterhouse alumnus, to help save their College, not realising that he is another who had an unpleasant time when he was there.

In the end, the scheming is overtaken by events, triggered by the grisly fate of Zipser (John Sessions), one of the despised "scholars" - indeed, apparently the only one in the College: he tries in vain to find a supervisor for his thesis on the influence of pumpernickel on the history of Westphalia. It is his storyline that turns the satire into farce - this is Tom Sharpe after all - and then into tragedy, albeit still a rather comic tragedy.

All seems set for Sir Godber's final victory, except there are still a couple of twists left to go. The biggest is perhaps not entirely unpredictable, but it is executed beautifully, and the ending is hugely satisfying.

Of course, in real life, Sir Godber really did win in the end. One could not make Porterhouse Blue today as a contemporary show because if Porterhouse existed it would now be a very different place, a far more serious place. Academic management is far more efficient, academic careers are much busier and less secure, and the higher end of higher education is now more interested in, well, actual education.

Where the admissions policies of snobbish Colleges once favoured "gentlemen" over "scholars," there is now a reverse snobbery where "diversity policies" favour the State educated over the privately educated. Greater access to higher education, meritocracy, value for taxpayers' money, academic excellence, and the like are obviously good things. Yet something has been lost along the way.

While Porterhouse Blue was obviously intended as a satire on what was clearly an unsatisfactory situation, it was at the same time, perhaps unintentionally, a tribute to a world that was already passing. It is certainly a well produced evocation of that world, and, even if it exaggerated its shortcomings, it also illustrated its splendours and reminded us that academic communities were once real communities. If, like all communities, they had their negative aspects, they were more than degree factories - mass production lines for qualifications.

Above all it must be remembered that, contrary to what Porterhouse Blue suggests, the pampered leisure of the old "Dons" enabled some of them at least to focus on work of enduring value. Do today's educational hot houses give what are meant to be our greatest minds the same time and space to step back and think about the bigger picture?

So while Porterhouse Blue, was, and remains, very, very funny, there is always an air of melancholy about it, a lament for the sense of tradition that the show was helping to kill by ridiculing.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on April 21st, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.