Gormenghast

2000 - United Kingdom‘While it was acclaimed by many, the production was not the huge popular success the BBC envisaged’

Review by John Winterson Richards

If you can imagine how Game of Thrones might have looked if it had been directed by Terry Gilliam you have a fair picture of the BBC's adaptation of Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast novels.

One cannot help feeling that Peake himself would have been more at home in the more surrealist Monty Python generation than he was in his own. He wrote epic fantasy around the same time as JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis, but his work had little in common with theirs. He was younger, and informed by different life experiences, including being brought up by missionary parents in China, and later being traumatised by witnessing the immediate aftermath of the liberation of Belsen concentration camp. His attitudes towards Christianity, which influenced his work as their own faith influenced Tolkien and Lewis, are more complicated than their Roman Catholic and Anglican orthodoxy. This ambiguity is most apparent in his Mr Pye, which was adapted for television very effectively with Sir Derek Jacobi in the title role, and, to a lesser extent, in the Gormenghast novels themselves, in which the obsession with ritual, in what has been described as a "Godless religion," is a major theme.

Peake was in fact, first and foremost, a visual artist, one of the leading illustrators of his time. He just so happened to be one of those intimidatingly multitalented people who seem to excel at whatever they attempt. Writing was therefore a secondary interest at which he turned out to be disconcertingly good. Where Tolkien and Lewis, as Professors of Literature, had a particular fascination with words themselves, Peake's imagination is more visual. Where the Inklings' work is consciously part of the literary traditions in which they were acknowledged experts, Peake is less encumbered by history and lets his mind run free, sometimes to very strange places. Indeed, the Gormenghast novels are to a great extent a protest against tradition, and academia is a particular target of their satire. Despite that, Lewis, who maintained a friendly correspondence with Peake, thought highly of the novels (so it is likely that his close friend Tolkien, who was in any case famously widely read, was also aware of them, but we do not know what he thought of them, and it is hard to imagine him liking them).

Given that Peake died young, we cannot be certain where he would have taken the story, but, as they stand, the novels' distinctly gloomy world view means they have never achieved the popularity of Middle Earth and Narnia, but they were a critical success and those who like them tend to like them a lot. They have been adapted frequently and even turned into an opera.

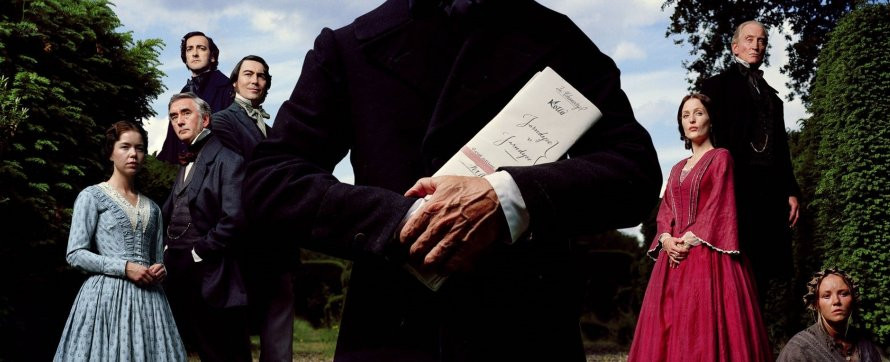

This is perhaps surprising because they are not particularly dramatic. They have been described as a "fantasy of manners." They have no talking animals or epic battles. Their characters are recognisable types in an extraordinary environment. They are more about atmosphere than action. With the exceptions of the villain and the (eventual) hero, most of the characters are very passive, which is the point of much of the satire. Indeed, the main character is arguably a building, the Gormenghast of the title, a huge sprawling castle complex in an advanced state of decay that dominates an isolated, economically backward, and culturally static ancient Earldom. This represents both a challenge and an opportunity for an adaptor in any visual medium.

The design of the BBC adaptation was influenced by China, where Peake was raised, and in particular by the Forbidden City, and also by Lhasa in Tibet, both of which shared Gormenghast's social stasis and fixation with purposeless ritual. It should, however, be noted, that, although Peake's son, Sebastian, mentions on the official Peake website that Mervyn's father visited the Forbidden City by special invitation soon after its abandonment, there is no mention of Mervyn himself going with him, or of either of them ever visiting Tibet. Mervyn seems to have conceived Gormenghast as something more in the Gothic style.

Yet he would surely have appreciated the imagination that went into the BBC production, and also the clever technique in its realisation. Today it would be an easy job for CGI, but then it was necessary to build a complete model - which was then photographed under water to give it more of a sense of substance. Whether or not they are true to Peake, the images stick in the mind longer than the story.

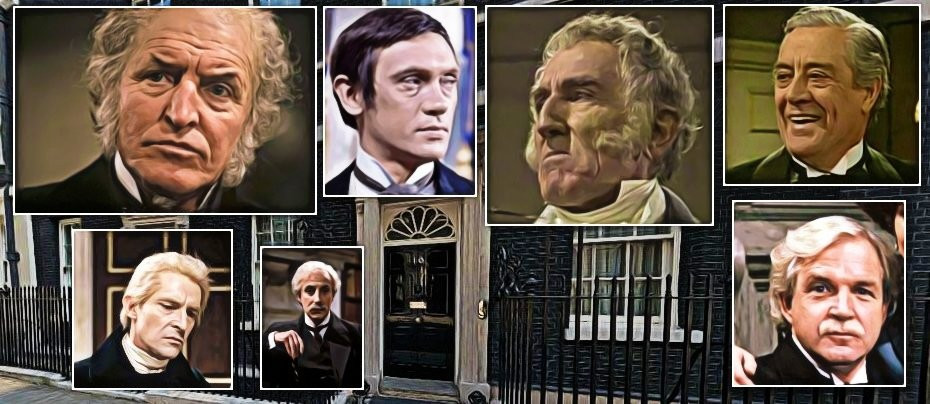

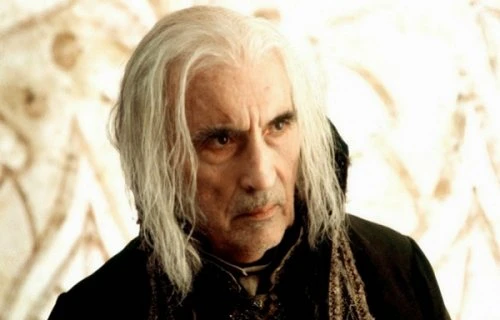

It was obviously a very expensive production. Its status as a prestige project was enhanced by a full orchestral theme commissioned from Sir Richard Rodney Bennett, a choral theme from Sir John Tavener, and a truly stellar cast. Christopher Lee, on the verge of his late career Renaissance in the Lord of the Rings and Star Wars films, is very effective against type as the fanatically loyal servant Flay. His famously commanding figure, familiar from so many patrician leader-type roles, is apparently diminished by his servile stoop. Incidentally, it is no surprise that Lee, who seems to have known everyone, was acquainted with Peake: they kept bumping into each other at Harrods. Ian Richardson is poignant as the 76th Earl of Groan, who, exhausted by a life wasted in the performance of meaningless ritual, just wants to become an owl (which he sort of does). Celia Imrie, a very talented actress who really deserves greater recognition, is at her best as his imperious wife, who seems to care for no one but her legion of pet cats and her tame white rook, Master Chalk, but who proves to be very sensible when the occasion demands.

By the way, the rook is a genuine white rook - apparently the only one in the world at the time as far as the producers knew - and whoever kept all those cats together at the same time deserves serious respect.

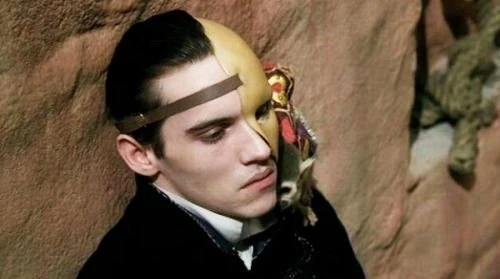

The most interesting character is the villain, Steerpike who is simultaneously, at least as played by Jonathan Rhys Meyers, both attractive and repellent. Like Shakespeare's Richard III, he sets out deliberately to be a villain but one cannot help respecting his enterprise and the desire to improve his lot that is missing in practically all the other characters, except Titus, the 77th Earl, in the final episode. One even has to sympathise with Steerpike as the victim of a rigid class system and admire his willingness to try to do something about it. If his capacity to do so is limited by his growing insanity, that is hardly his fault. Gormenghast is an insane place.

Zoe Wanamaker and Lynsey Baxter are funny and sad as the dim but ambitious twins whose simple minded vanity is exploited mercilessly by the cruel, manipulative Steerpike. John Sessions maintains a nice ambiguity as a physician who is quite perceptive, and not without compassion, beneath a thick layer of sycophancy. Fiona Shaw is tragically comic as his desperate spinster sister. Richard Griffiths is suitably odious as the abusive cook. June Brown is ideal as the faithful but fussy Nanny Slagg.

Warren Mitchell is the pedantic Master of Ritual who runs, and ruins, everyone's lives. Windsor Davies is well cast in an apparently serious role as a Captain of the Guards and it is frustrating that a heavy hint of significant personal conflict with Steerpike leads nowhere. Eric Sykes and Gregor Fisher also have disappointingly small roles as servants. A job lot of other leading British comedians of the time, including Spike Milligan, Stephen Fry, Mark Williams, Martin Clunes, Steve Pemberton, Phil Cornwell, and James Dreyfus play the various Professors employed to educate the young Earl, but, to be honest, their scenes are too long, not that funny, and wholly superfluous.

This is part of a broader problem with the piece. The tone is uncertain. Peake's writing tends to combine whimsy with a very wide and deep dark streak, and it is difficult to get the balance right. Are we meant to be amused by what we are watching? It is sometimes hard to be certain what we are supposed to be feeling, if anything.

There is also a problem with the pacing. The adaptation covers only the first two books of the published trilogy (a freestanding novella and a few pages of a fourth novel are all we have of the rest of what was planned as a cycle of several novels). The hero, Titus, only really wins his agency in the last of the four episodes. The focus in the first two, in as much as they have a focus, is on his father while not much happens at all in the third. So it feels as if the story never really gets started until it is almost over.

This is, to an extent, a reflection of the novels. It is only in the third that Titus, and the reader, leaves Gormenghast. This changes the nature of the story completely, so one understands why the BBC stopped where it did, or at least reserved the rest for a sequel that never happened. As it is, the adaptation is left in need of a third act, and that after a second act which seems very perfunctory.

While it was acclaimed by many, the production was not the huge popular success the BBC envisaged when they approved the substantial budget, nor did it become a particular "cult" item by way of consolation. Fans of the books, a crucial target market in any such adaptation, were divided about it - possibly because each had their own vision of Peake's vision - and it probably added few to their number.

It was, in any case, soon overshadowed by the success of Sir Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings feature films, which really showed how these things should be done. These were followed by the more qualified success of a cinematic adaptation of Lewis' Narnia books. Since then, Gormenghast has been largely forgotten, except by fans. At the time of writing, Neil Gaiman has been commissioned to write a new adaptation. The Good Omens and The Sandman writer is certainly the man to fix the books' pacing, but one does wonder how his writing style will suit the nature of the source material, which is in many ways the direct opposite of his own novels.

Either way, his attempt should at least prompt a reassessment of the BBC version. It deserves a higher profile and reputation. Even if it did not rise above the structural problems inherent in the books, it was well produced, well cast, and well acted, and, while one can understand why its dark imagery was not attractive to a wider audience, that imagery is both powerful and genuinely original.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 27th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.