Hot Metal

1986 - United KingdomReview: JWR

The scriptwriting team of Andrew Marshall and David Renwick has never quite achieved the status of Clement and La Frenais, or Croft and Perry, or Croft and Lloyd, or Jay and Lynn, or even Marks and Gran. Their solo work, especially Renwick's, has received more acclaim.

Yet Marshall and Renwick deserve more respect as a duo. Ranked purely as satirists, they displayed a better eye for subjects of their satires than most of their competitors, even if some of the others showed a greater subtlety of character and plot.

In 1982, they set out their wares in Whoops Apocalypse, which took a rather scattershot approach to a number of different targets that were topical at that moment. As usual with scattershot, some bits hit while others did not. They seem to have reflected on this, so their next project, Hot Metal, was aimed more tightly at a specific target, the British tabloid press.

The result was a show that, unlike Whoops Apocalypse, could be remade today with very little need to update the scripts. Only the technology has changed. If anything, the excesses presented in Hot Metal as satirical absurdities are closer than ever to what is actually done.

Of course, the press has long been the object of well deserved cynicism on the part of other media. The references to the real life "yellow journalism" of William Randolph Hearst in 'Citizen Kane' have their clear parallels today. The best satire on journalism is still the 1928 play 'The Front Page' and its subsequent film versions. Its enduring superiority is due in large part to it having written by an experienced journalist, Ben Hecht. What he presents in 'The Front Page' is nothing compared with some of the true stories he recounts in his memoirs, which he obviously realised were too unbelievable for a work of fiction.

The printed press is no longer as powerful as it once was - if it ever really was: among the many things it exaggerates is its own influence. In response to the growth of digital media, it complains rather hypocritically about "fake news" on the internet. It has only itself to blame. While there is indeed substance to the complaint, there is nothing on the internet that was not pioneered by "mainstream" print journalism long ago. If anything, scepticism about the press has to an extent immunised the public against some of the web's absurdities. We are actually used to "fake news" and may be better at spotting it than the media give us credit.

So, in retrospect, there is sometimes a touching innocence about Hot Metal. Yet it still reminds us that there was no Golden Age of journalistic integrity before the internet.

The basic plot concerns the takeover of a once respected but long ailing Fleet Street journal, the fictional 'Daily Crucible,' by a ruthless media tycoon. Like many such take overs at that time, it is accompanied by loud declarations, prompted by the Monopolies Commission, that the new management will respect the editorial independence of the publication.

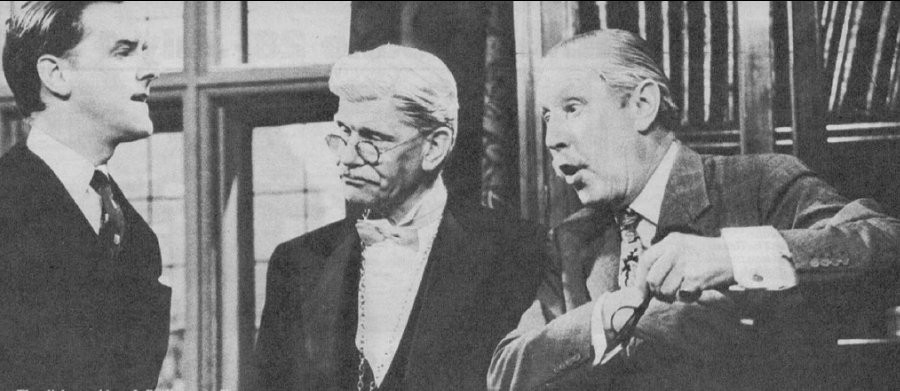

To ensure that independence, the new proprietor then appoints a new editor ...who could almost be his clone. Indeed, both are played by the same actor, Robert Hardy.

This is the central theme in Hot Metal, that the supposedly arm's length proprietor and his supposedly independent editor are practically identical. It was a deliberate reference to several such relationships in real life at the time. This rather obvious satirical point was underlined by a long running gag that the proprietor and the editor were never actually seen in the same place at the same time, implying that they were in fact the same person. It was actually quite a surprise to discover that they were not.

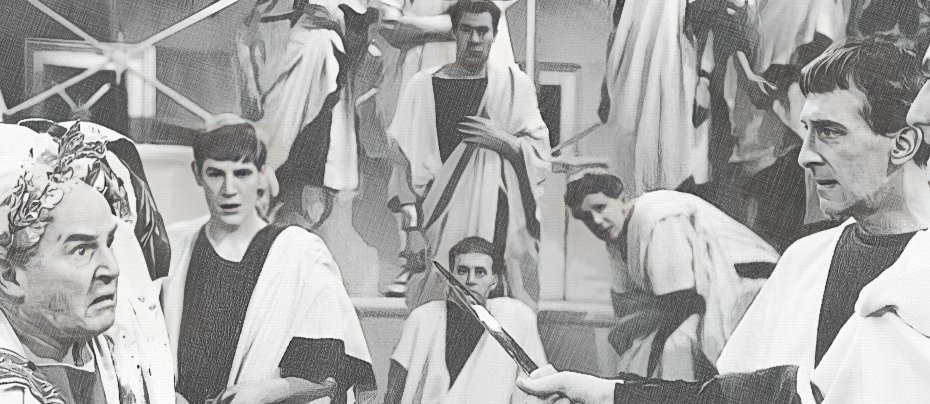

It seems appropriate to pause at this point to pay tribute to another underappreciated talent. Robert Hardy was a leading member, along with the likes of Sir Ian Holm, Sir Derek Jacobi, and David Warner, of a generation who revolutionised the British stage by introducing a more modern, realistic style to acting, not least in Shakespeare and the classics. A friend of Richard Burton, a student of C S Lewis and J R R Tolkien, and one of the first to make the hitherto disreputable leap from Oxford graduate to a professional acting career, Hardy was arguably the most influential Henry V between Olivier and Branagh.

He is therefore a pivotal figure in recent British culture, but most remember him only as an irascible vet and his generation's "go to guy" to play Sir Winston Churchill following his great success in Winston Churchill: the Wilderness Years. While he enjoyed a distinguished career by any standards, one cannot help feeling that, as with some of his other outstanding contemporaries on the stage, film and television rarely gave him the leading roles that enabled him to show off his full talents.

So Hot Metal is in fact one of the best showcases there is for his versatility. He excels in the tricky task of presenting two roles that are both sufficiently similar and sufficiently different for us to remain unsure whether they are two separate people. He carries it off with great skill, demonstrating an unexpected talent for comedy.

The proprietor, Terrence "Twiggy" Rathbone, is a domineering authority figure, referencing Conrad Black and Rupert Murdoch, except with the added menace of an upper class British accent. By contrast, the editor, Russell Spam, is cheerily vulgar and almost eager to please. Both are superb comic characters in their own right, but it is the subtle distinctions between them that indicate a trained Shakespearean technician is at work.

For all Hardy's mastery in the lead, the most memorable character is the wholly unprincipled investigative journalist Greg Kettle, played by Richard Kane. Kettle is simply one of the greatest comic characters of all time and would probably be synonymous with gutter journalism as a whole to this day had the show been better known.

He is basically the ruthless Kirk Douglas muckraker in 'Ace in the Hole,' but without the redeeming thin sliver of conscience and played for laughs. He has no morals and no sense of social restraint. He barges in to where a potential story is to be found, giving himself a spurious authority by announcing that he is from "Her Majesty's Press." Where there is no story to be found, he will engineer it - using a pin and a contraceptive as a pretext for a scoop on a possible Royal baby. Where he cannot make a story, he will make it up - so that a harmless old Vicar becomes a Marxist agent and then a werewolf.

Ben Hecht would have loved him. This is why Britain has stronger libel laws than most nations.

Rathbone and Spam back Kettle because his outrageous headlines sell newspapers. He is the despair of the former editor, Harry Stringer, an honest newsman - yes, there is such a thing - "promoted" when Rathbone took over to make room for Spam. This "promotion" to the meaningless post of "Executive Managing Editor" means he has to move his office - to a lift. Stringer is played by Geoffrey Palmer with that peculiarly British air of strained dignity of which Palmer is the acknowledged Grand Master.

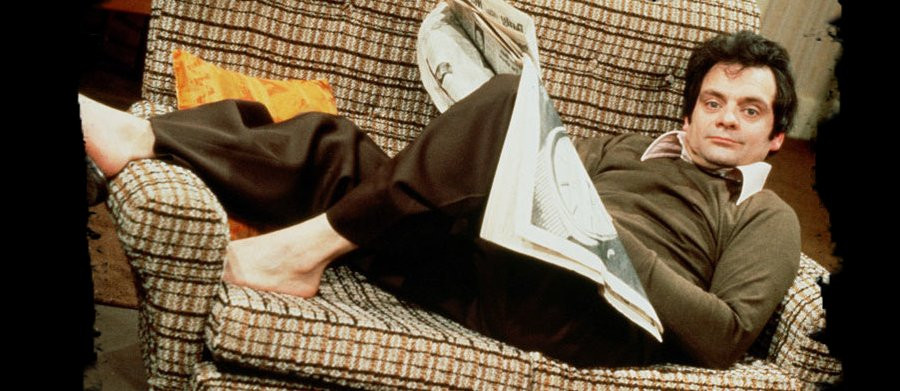

After Stringer disappears mysteriously between the first and second seasons, he was replaced by Richard Lipton, once a serious and respected journalist, now seeking to restore his credibility after slumming it on daytime television. Lipton is played by Richard Wilson, later the star of Renwick's One Foot in the Grave.

Lipton encourages an eager young reporter, Maggie Troon (Caroline Milmoe), to pursue an important story, in much the same way that Stringer tried to encourage a similar character, Bill Tytla (John Gordon Sinclair), to do the same in the first season. Their plotlines are supposed to provide the spines for their respective seasons, but in truth they turn out to be secondary. It is the machinations of Rathbone, Spam, and, above all, Kettle that stick in the memories of those who watched the show.

Sad to say, that is not too many. If Hot Metal had been shown on BBC, Rathbone, Spam, and Kettle would have become household names. If it had been a Channel 4 show, it might at least been a "cult" hit. Perhaps Hot Metal never got the status it deserved because, like Whoops Apocalypse, it was on ITV and the commercial philosophy of ITV has never sat easily with satire. The commissioning of the likes of Hot Metal and Whoops Apocalypse were part of a deliberate attempt to take ITV's image more upmarket, but that was asking too much of them.

In any case, Hot Metal was soon overshadowed by a more modern media satire, Channel 4's Drop the Dead Donkey, which was set in the more dynamic environment of a television news room. While it owed a lot to Hot Metal, including its multistrand storylines and its cynicism, Drop the Dead Donkey was more realistic, less stylised, and faster paced. Yet in some respects, Drop the Dead Donkey has aged more rapidly than Hot Metal. Where Drop the Dead Donkey is fixed in the 1990s, dated now because it was topical then, the Hot Metal characters are timeless archetypes. In spite of constant predictions of its imminent demise, the printed newspaper is still with us, and, so long as it remains, so will the glorious tradition of satirising it.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on June 7th, 2020. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.