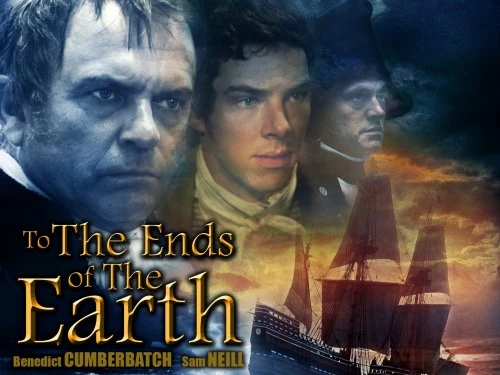

To The Ends of The Earth

2005 - United Kingdoman engaging performance by Benedict Cumberbatch

To the Ends of the Earth review by John Winterson Richards

A somewhat artificial distinction between literary and popular fiction has grown in recent years. This was not always so: most of what we think of as great literary works, like those of Austen, Scott, the Brontes, and Dickens, were intended for a general readership, not some incestuous "literary elite”, and were usually very popular when first published. Great novelists were first and foremost great storytellers. The self-consciously literary have since become more snobbish about storytelling which includes such vulgar devices as action and excitement. It is still necessary to tell good stories to succeed in the popular market, but a literary novel is usually more introspective. So it is not surprising that, while popular fiction is often adapted for the big and small screens to great success, acclaimed literary fiction often fails to translate because inner feelings are harder to film. Adaptations of the sort of novels that win prestigious Prizes have usually been critical and commercial disappointments.

There are notable exceptions to this, for example the BBC adaptation of Wolf Hall, which is actually superior in some respects to Dame Hilary Mantel's Booker Prize winning novels on which it was based. It could be argued that the same is true of the BBC adaptation of Nobel Prize winner Sir William Golding's To the Ends of the Earth trilogy of novels, the first of which, Rites of Passage, also won the Booker Prize. While it would perhaps be going too far to suggest the adaptation of To the Ends of the Earth is "better" than the novels, the acting and production design certainly add a lot to the story, even if some of the subtlety of the writing is lost. It is fair to say the novels and the adaptation both play to the strengths of their respective media.

The adaptation stays surprisingly close to the books, not least in its structure. Each of the three parts of the miniseries sticks, more or less, to the plot of one of the novels of the trilogy. This is a wise decision.

In the first part of the miniseries, which shares the title of the first novel, Rites of Passage, we meet our protagonist and first person narrator Edmund Talbot, an intelligent, and vaguely well meaning, but ignorant and entitled young man on his way to Australia towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars to take up his first appointment in what everyone, above all Edmund himself, assumes will be a glittering career. With the Royal Navy at full stretch, he has to travel on an old ship of the line which is now dangerously unfit for a long voyage. Its officers are not high fliers but men all too aware that they are likely to find themselves unemployed "on the beach" once the Wars end. Edmund must share several months in close confinement with several other civilian passengers, including the socially inept Reverend Colley, whose squalid tragicomedy provides the main storyline for the first novel and episode.

The second novel and episode, Close Quarters, begins with what looks like an excursion into Hornblower territory, as a menacing warship is sighted, before taking an unexpected turn into Austen country.

The third novel and episode, Fire Down Below, is a tense race against time as it becomes a real issue whether the ship will fall apart before it reaches Australia. Some surprising new friendships develop under stress.

The whole trilogy is therefore the story of a single, very lengthy voyage. At the same time, it functions as a bildungsroman, a coming of age story. Edmund himself eventually begins to see it that way - until a rather brutal conclusion destroys his own literary view of himself as hero of his own saga. Nevertheless he does appear to have matured a little.

It is also something of a comedy of manners. The Regency period was a time of transition and of conflict. There was a definite "culture war" between the louche aristocracy of the 18th Century, whose attitudes Edmund shares, and the rise of Evangelical Christianity, especially among the middle classes, that was to establish the strict morality of the high Victorian period. The time of Beau Brummell that Thackeray would satirise in Vanity Fair was ending and the better mannered time of Jane Austen had begun. Most of the other passengers are grotesques straight out of a Gillray caricature; heavy drinkers associated with the old culture - but, while the Reverend Colley proves a poor representative of the new Evangelism, the governess Miss Granham is a character Austen and the Bronte Sisters would recognise.

What everyone shared was an awareness that this was a culture in which every aspect of one's life depended on one's perceived social status, a topic that the trilogy explores very cleverly.

It is important to note that, although he moves in aristocratic circles, and the sailors sometimes address him as "lord," Edmund himself is not an aristocrat. When he fantasises about addressing Parliament, he is aware that his nomination to a "pocket Borough" is well within the realm of possibility, but he has no title or estates of his own. His social status depends entirely on everyone being aware that the First Lord of the Admiralty is his Godfather. The novels imply that this is understood to be a euphemism for a much closer, if strictly unofficial, paternal relationship. This is why this very young man with no rank is treated with extraordinary deference even by the Captain and the officers of the ship. A single word from him could make or break their careers. It is a perfect illustration of the point made by Tolstoy in War and Peace about there being two hierarchies, the formal one and the one that matters.

Yet as the trilogy progresses there is a definite shift in power between Edmund and Miss Granham. At first she is very self-conscious about her decayed status, the daughter of a Canon of a major Cathedral forced to find employment as a governess. Marriage seems to give her a new confidence, or perhaps enables her to rediscover a strength that was always there, and even Edmund comes to regard her with genuine respect. At their final meeting she is very much in control. This seems to be emblematic of a very definite shift in the power between classes, and between different attitudes, around this time. Edmund himself is changed by it. At the end of his voyage he seems less of the hard drinking, womanizing semi-aristocrat and instead a man prepared to make his own way in the world, capable of self sacrifice, and perhaps ready for a proper marriage.

Much of the sympathy we have for him by this point is due to an engaging performance by Benedict Cumberbatch. Although still relatively young, he was already marked as a rising talent with a good curriculum vitae behind him. Playing the title role in Hawking had recently earned him the Golden Nymph at the Monte-Carlo Television Festival and To the Ends of the Earth was to win him his second.

Jared Harris was another actor beginning to make his mark at the time. He convinces completely as the blustering Captain whose consciousness of the power of his office masks a deeper insecurity. That his only real interest is in his plants seems to reference the famous Captain Bligh, a great seaman whose assertive command style may have been an attempt to hide a sense of inadequacy. Charles Dance provides a wonderful contrast as another Captain, one who happens to be blessed with the natural self confidence of a Charles Dance character.

Victoria Hamilton has a wonderfully direct gaze as Miss Granham. The always watchable Sam Neill turns up as a famous Radical who seems at first no more than a bad tempered windbag but who gradually reveals a more human and humane side to himself. Cheryl Campbell and Joanna Page are well cast as Dance's wife and ward, even if there is something surreal about the episode in which they appear, a romantic interlude in a seafaring tale. While there is no doubt that it happens, we are left wondering how much of the way it is presented to us is a reflection of a severe concussion from which Edmund is then suffering. The same is true of an uncomfortably eerie subplot involving the excellent Brian Pettifer as the servant assigned to look after Edmund.

This emphasises the point that Edmund is something of an unreliable narrator and since we are seeing things from his perspective, we cannot be certain that some of what we are being shown is not slightly exaggerated or stylised. It is perhaps in the nature of adaptation that the script punches up the humour more than the novel and gives the ending a slightly more optimistic tone. Is this Edmund's way of trying to deal psychologically with his misadventures?

Indeed, is the ship quite as squalid as it is presented or is this simply the way the fastidious Edmund sees it? Either way, the design departments do a superb job in conveying how dilapidated it is, with peeling paint, leaks, and dirt everywhere. The contrast with the neat little frigate captained by Dance is telling. The latter is what we have come to expect from historical fiction about the period, like the Hornblower novels of C S Forester and the Aubrey-Maturin novels of Patrick O'Brian, in which the Captains and crews are always portrayed as supremely efficient. That may indeed have been true of the elite frigates and line of battle ships, but To the Ends of the Earth is almost certainly correct that much lower standards probably prevailed on older vessels assigned to routine transport duties.

The comparison with O'Brian is helpful because the television adaptation of Golding's trilogy came out soon after an acclaimed cinematic adaptation of O'Brian, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, which really is the gold standard for historical drama. It rather undermines the whole notion of superior literary fiction that the supposedly more popular O'Brian has the more accurate sense of time and place, and the same is true of their respective adaptations. Nevertheless, the very fact that To the Ends of the Earth is worthy of mention in the context of Master and Commander is in itself greatly to its credit, and watching the former is perhaps a useful antidote to the latter's tendency to distract from much of the unpleasantness of life at sea around Nelson's time.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on February 16th, 2024. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.