Stalin

1992 - United StatesStalin is more a biography than a political history

Review by John Winterson Richards

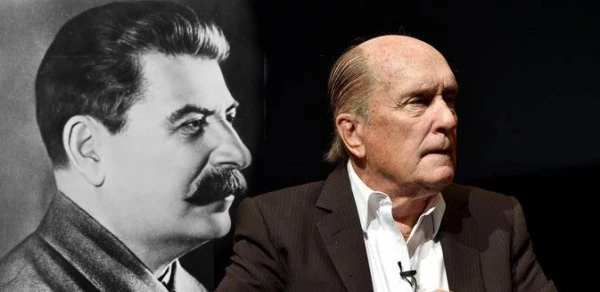

Robert Duvall is arguably the greatest screen actor of his generation. If you think that accolade belongs to a showier performer like Brando or Pacino just look at how Duvall quietly steals scenes from them in The Godfather Saga. However, when once asked about his favourite role, Duvall himself did not mention The Godfather, or his legendary turn in Apocalypse Now, or the exquisite Tender Mercies, or his personal passion project (no pun intended) The Apostle, or the extremely likeable characters he played in Lonesome Dove, Open Range, and Secondhand Lions. No. He said it was Stalin.

Given Duvall's politics - he is one of Hollywood's few open conservatives - we can be fairly certain he did not mean Stalin the man but rather how, as an actor, he overcame the challenges of playing the Soviet Dictator in Stalin, a prestigious "television movie" made at a time when the Soviet Union was belatedly trying to come to terms with Stalin's complicated legacy.

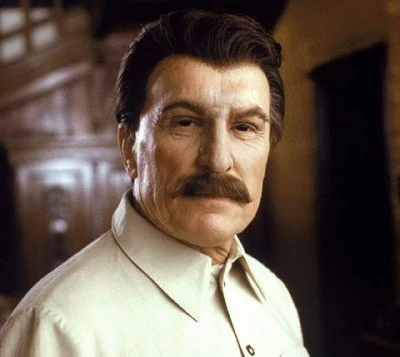

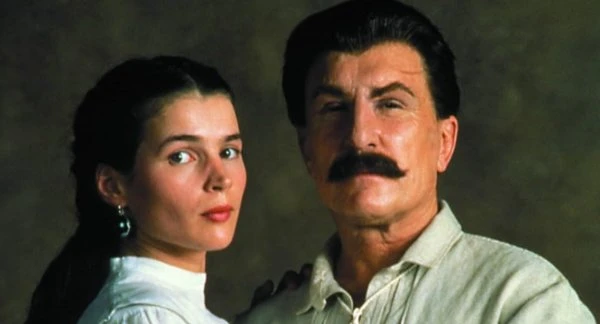

The most obvious challenge is that Duvall looks nothing like Stalin. For a start Duvall is too tall and he lacks Stalin's withered arm. More importantly, there is little facial resemblance. Duvall therefore had to assume what was for the time a ground-breaking combination of prosthetics and make up. That this left him with a certain immobility of expression actually turned out to his advantage because it evokes Stalin's famous inscrutability to perfection.

His relative height also enabled him to be more physically intimidating than Stalin, which may not be so historically accurate but is certainly dramatically helpful. From start to finish Duvall's Stalin is nothing if not frightening. The viewer can well believe that this is a man capable of getting another man to shoot himself on the spot.

He is also nothing if not fascinating, as was his real life counterpart. Like Mussolini: the Untold Story, the age of the big name leading man demanded that the script joins the story when the protagonist is already in power, or at least on the verge of power. This does, however, leave untold, perhaps for another day, the astonishing story of how Stalin rose to power in the first place. It is possible to paint the young Stalin, startlingly handsome, a genuinely talented poet, and the leader of a gang which carried out a series of daring armed robberies, as a romantic hero. At the same time, contrary to later attempts to portray him as an interloper who spoilt the Russian Revolution, he was crucial to the success of the Bolshevik project, as its principal "fundraiser" (i.e. those robberies), editor of Pravda, and the Party's most efficient organiser, as well as the only member of the Politburo in October 1917 with real working class credentials. Stalin hints at some of this but never has the opportunity to show it all.

It does get to show the dark side of Stalin in power. The silly debate about whether Stalin's crimes were worse than Hitler's or Mussolini's misses the point: all belong on the same gallows and the difference between them is only one of degree (as Stalin himself is reputed to have pointed out, one death is a tragedy, a million is a statistic). What we can say is that Stalin was both the most ruthless and the most successful of the three archvillains of the Mid 20th Century, and possibly the most successful because he was the most ruthless. While Hitler and Mussolini may not have been dictionary definition psychopaths, Stalin almost certainly was. Executions within Hitler's inner circle and Mussolini's were rare, and usually signs of the times when they felt they were losing their grip on power, but Stalin had absolutely no compunction about killing even those closest to him at any moment. Everyone around him lived in a constant state of fear. He seems to have liked it that way.

This is evoked very convincingly in Stalin the movie. We are shown the drunkenness and false good humour of dinners at the Kremlin at which the highest Party bosses, powerful men in their own departments and well known figures on the international stage, acted as buffoons in order to please their master, who rewarded them with visible contempt. That is apparently how it really was.

Yet, like many high functioning psychopaths, Stalin had great charm when he wanted to use it, and there is no denying that he generated sincere devotion and intense loyalty, exemplified in Stalin by his uncritical father-in-law (played by Frank Finlay), even if one wonders if there was an element of Stockholm Syndrome about it all. Psychopaths sometimes also retain a strangely incongruous sentimental streak, and Duvall's Stalin is probably accurate to suggest that the historical Stalin honestly liked to think of himself as a good father, husband, and friend, and was disappointed when, as he saw it, others let him down by forcing him to kill them.

Quite apart from his psychopathic tendency, Stalin's extreme paranoia was exacerbated by his years as a revolutionary on the run and then as a ruler - and, in his defence, it has to be said that others really were out to get him in both capacities and prepared to exploit the slightest sign of weakness on his part even, or especially, when he had achieved absolute power. On top of this, he always retained a sense of inadequacy due to his upbringing. This sometimes manifested itself in the vulgarity and loss of control that got him into trouble with Lenin. All these psychological ingredients formed a lethal cocktail, which Duvall reconstructs with complete authenticity, so that one forgets very quickly that one is watching a relatively tall American actor and not the real Stalin, and it is Duvall who tends to pop up in the mind whenever one thinks of Stalin after having seen his performance. He has every right to be proud of his work here.

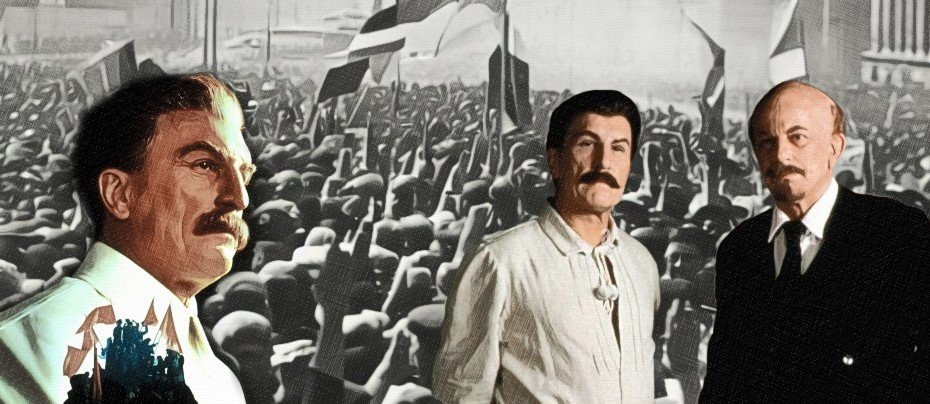

He is backed by a very strong supporting cast. Lenin is played by Maximilian Schell, who had played another of Russia's great monomaniac "modernisers" in Peter the Great. Schell also looks little like his historical counterpart, and he gives us a surprisingly nervous Lenin, far from the image of the detached intellectual the Bolsheviks promoted and which even the Western media never really challenged. Schell's version may well be the more accurate. The Bolsheviks are in general presented as a rather neurotic bunch, which, given their life stories, is both credible and understandable.

Most are played by British actors, including Finlay as Stalin's obliging father-in-law, Dame Joan Plowright as his wife (who therefore had the dubious honour of the title of Stalin's mother-in-law), Julia Ormond as their daughter who had the poor judgement to fall in love and then out of love with Stalin, Joanna Roth as the rebellious daughter Stalin loved as sincerely as he could love anyone, Daniel Massey as Stalin's egotistical rival Trotsky, Jim Carter as Stalin's best friend (spoiler: do not get too fond of him), Stella Gonet as his best friend's wife (ditto), Kevin McNally as a loyal Stalinist who is nevertheless too popular for his own good (ditto), Clive Merrison as the great survivor Molotov, and John Bowe as the sycophantic Marshal Voroshilov, who is given a great scene when his mask slips in a moment of high emotion, followed immediately by the inevitable moment of horror when he realises what he has just done. Miriam Margolyes is well cast as Lenin's wife, but it is worth noting that, contrary to what is implied here, she retained Ministerial office under Stalin until her death (which, it is also worth noting, some claimed was hastened by a poisoned birthday cake sent by Stalin).

Colin Jeavons, Matyas Usztics, and Roshan Seth are appropriately unpleasant as successive and increasingly nasty Chiefs of the NKVD, Stalin's feared security service of which the Gestapo was a pale copy. There is some justice in the fact that in the end all were killed as they had killed so many others, shot in the head after fixed trials. The first two were shot on Stalin's orders for doing what he told them to do. The last of them, Lavrentiy Beria, played by Seth, may be the most unreservedly evil man who ever lived: it is impossible to find anything to be said in his favour, except that he was efficient at what he did, which, in his case, was hardly a good thing.

Jeroen Krabbe brings a poignant quality to Bukharin, the most likeable of the Bolsheviks. At least he had qualms about some of the things they did, but he still did them. The point perhaps should have been emphasised more in Stalin that most of the characters we meet had blood on their hands, and what Stalin did to them was no more than they had done to others, or at least approved.

Indeed, it was a common criticism of the film when it was first shown that it showed very little of the suffering of millions beyond the narrow social circle within the Kremlin. That was of course the whole point. Those responsible for the suffering were to a great extent isolated from it - by choice.

One of the big selling points of Stalin was that it was one of the first major Western productions to be granted permission to film inside the Kremlin as part of Mikhail Gorbachev's policy of glasnost or "openness" - and, as it turned out, one of the last, since Mr Gorbachev had lost power by the time it was aired. To be honest, the mostly utilitarian interiors are not as spectacular as one might have imagined. However, one does get a sense of how lost and out of place this very tight knit, inward looking band of social misfits and criminals, which is what the revolutionaries were, must have seemed and felt in this gigantic palace complex after suddenly, and, if they were honest, unexpectedly, taking control of a huge empire. In between drinking wine looted from aristocrats, all but one of them had very little idea what they wanted to do. The only one who did is the one with his name in the title: there is a valuable political lesson there.

Yet Stalin is more a biography than a political history. The distinction is an important one, not least because it is unfair to criticise it for not being what it is not trying to be. This is history only as glimpsed from the perspective of Joseph Stalin and those immediately around him, not an attempt at objective analysis. As such, as human drama, it is a great success. This is not to say it is a pleasant watch. How could it be, given the protagonist and the events it portrays? It is nevertheless great television, well made, very well acted by the whole cast, and with a truth and importance that is now very rare In historical drama.

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Seen this show? How do you rate it?

Published on September 14th, 2023. Written by John Winterson Richards for Television Heaven.